Mimi Roots is worried about her ninety year old mother, Maria.

Maria lives alone and has multiple health issues: congestive heart failure, asthma, arthritis, gastrointestinal issues, and a thyroid that was surgically removed. She receives care from five specialists and her family doctor – and each prescribes their own set of medications. Maria takes a grand total of thirteen different medications, many of which need to be taken more than once a day.

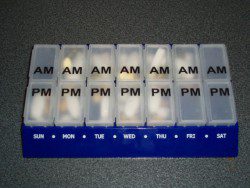

Most of her medications are blister packed for an additional cost by the pharmacist and arranged by the days of the week and time of day. However, not all of Maria’s medications fit into the blister pack and Mimi has found her mother has been confused about which bubble of medication to take. Just last year, Maria was hospitalized because she wasn’t taking a sufficient dose of her water pill. To ease the confusion, Mimi rearranges her mother’s medications by taking them out of the blister pack and putting them in a weekly dosette.

The complexities of aging

Maria’s story isn’t unusual. The vast majority of Canada’s seniors, 92%, live in private households. About one quarter of people 65 and older live alone. With increasing life expectancies, a greater number of people are living with several chronic and progressive medical conditions. Close to 15% of Canadians aged 65 and older also live with at least some cognitive impairment – difficulties with their memory or completing daily activities such as banking and cooking.

To further complicate things, many seniors have several physicians who provide different sets of prescriptions with few supports, familial or otherwise, to help sort through complicated medication regimens at home. A recent literature review found that 13 to 25% of seniors are prescribed five or more medications (known as polypharmacy). It also suggests that up to one third of people above the age of 85 used 10 or more types of medications in 2009.

It’s no wonder then that a substantial number of hospitalizations among the elderly are attributable to medication issues. Almost half of seniors who take five or more medications have been hospitalized as a result of adverse drug events, errors related to taking the wrong medication, the wrong dose of medication, or interactions between medications. Most of these adverse events are preventable.

What can go wrong with medication

Most seniors manage their own medications at home. Tricia Marck, Ariella Lang, and Marilyn Macdonald led a study focused on the safety issues of medication management in home care. The study included four provinces in Canada (Alberta, Ontario, Quebec, and Nova Scotia) and involved 8 home visits per province and focus groups with health care providers.

As part of the study, investigators took photographs of the methods seniors and their supports used to organize their medications at home. “We saw a range of strategies,” Marck commented, “from the very good to the very bad.”

Among the more worrisome strategies, some participants kept all of their medication containers unorganized in a bag or box. Others used large sticky notes taped on bottles or on calendars. These strategies created the possibilities of mixing up drugs, taking the wrong doses, or missing particular medications altogether.

One participant in the study routinely filled the weekly dosettes for herself and her husband with their medication containers lined on a dinner tray table, sitting on the couch, and watching TV. While this was among the better strategies, Marck commented that filling the dosette while distracted by the TV increased the likelihood of mistakes sorting medications.

Blister packing, a service offered by most pharmacies, is an option for some elderly who can pay for the additional costs. There are fewer sorting errors when pharmacists can blister pack medications than when people create their own dosettes. But blister packs aren’t foolproof and the potential for popping out the wrong bubble of medications always exists.

Transitions between different health care specialists and across different parts of the health care sectors make managing medications at home especially challenging among the elderly. As part of the home care study, Marck and colleagues identified significant communication issues across the sectors. “Communication among the sectors is quite poor,” according to Marck. “Integration isn’t happening particularly well and there is no shared documentation. When patients are discharged from hospital with changes to medications, it’s often by accident that home care providers become aware of these changes.” Many hospitals in Canada do provide electronic discharge plans to physicians involved in the care of a particular patient. These plans, however, are rarely – if ever – shared with health providers in the home care sector.

When patients are discharged from hospital, they are often unaware particular medications have been discontinued by the physician. William Ghali, a general internist at the University of Calgary, frequently sees patients admitted with acute kidney injury and discontinues medications they are taking that can be toxic to the kidney. “I might stop Ramipril [a type of heart medication] in a patient, but unless that’s clearly communicated to them or their family doctor, the patient’s family doctor may just restart that medication. The patient will likely refill the medication as well [putting them at risk for reinjuring their kidneys].”

Improving medication safety among seniors

Different segments of the Canadian health care system have explored a range of potential solutions to improve medication safety in the home among the elderly.

Best Possible Medication Histories

Within Canadian hospitals, Best Possible Medication Histories (BPMHs) are increasingly becoming the standard of care. The process of creating BPMHs, primarily led by hospital pharmacists, help reconcile patients’ medications. Hospital pharmacists engage in an intensive process to interview patients, review all medications from home, and contact all pharmacies patients use in order to develop definitive prescription lists. If there are discrepancies between the medications a patient takes and a list their pharmacies provide, the hospital pharmacist often offers recommendations to physicians about how to manage those inconsistencies.

However, seniors shouldn’t require an admission into hospital in order to obtain a formal review of their medications. Between 2008 and 2010, the Canadian Patient Safety Institute (CPSI), Safer Healthcare Now! (SHN!), Victorian Order of Nurses (VON) Canada, and the Institute for Safe Medication Practice (ISMP) Canada partnered on a pan-national Medication Reconciliation in Home Care Pilot Project. The project published a framework and a series of tools that enable health professionals in the home care sectors, such as family physicians, community nurses, and community pharmacists, to create lists similar to BPMHs for their own patients and clients. Alberta Health Services has also developed MedRec, a website devoted to resources for health professionals within hospitals and community based services to guide medication reconciliation practices. Their resources include a short interview guide and public education brochures.

Accreditation Canada has surveyed over 1200 health care organizations across the country, including hospitals, long-term care services, and home care organizations, to assess how well they engage in medication reconciliation processes. As of 2012, only 71% of organizations met the accreditation requirement of completing medication reconciliation at admission and 62% met the requirement at time of transfer or discharge. These were, however, substantial improvements from 2010 when compliance was only 47% at admission and 36% at discharge.

Explore new roles for pharmacists and paramedics

Home care organizations are also beginning to explore different ways to harness the expertise of different health professionals. Pharmacists, for example, have a knowledge base about medications that goes beyond their traditional roles of filling prescriptions and providing basic patient education. They can play critical roles within the community to reconcile medications and offer strategies to minimize “pill burden.”

A community pharmacist from the Community Care Access Centre (CCAC) visited Maria, Mimi’s mother, about three weeks ago. In Ontario, CCACs coordinate and deliver community and home health care. The pharmacist reviewed Maria’s medications and sent a list of recommended changes to her family doctor. “It was the first time someone sat down with us to explain my mother’s medications.” Cheryl Reid-Haughian, Director of Professional Practice, Knowledge, and Innovation at ParaMed Home Health Care noted that relationships between the agency’s nurses and pharmacists were critical to ensuring medications were appropriate. ParaMed Home Health Care specializes in providing home support, respite, and nursing care within the community.

According to Dr. Andrew Costa, Assistant Professor at McMaster University with expertise in elder care service and policy, community pharmacists have the capacity to identify issues with medications and provide patient education in ways that may prevent adverse events and reduce visits to emergency departments. Pharmacists who work in retail drug stores can provide the same services as community pharmacists that work for home care organizations. In most cases, Costa commented, it’s preferable to have the retail pharmacist provide an in-home consult to reconcile a person’s medications since that particular pharmacist already has an existing relationship with the patient. In Ontario, retail pharmacists are paid for providing in-home services such as reconciliation. Costa described more and more pharmacists are comfortable providing these services as their training has evolved to teach the new roles pharmacists provide.

Provinces such as Ontario are also expanding roles for paramedics. Some studies suggest the heaviest users of paramedic services and emergency rooms are the elderly who do not have significant social supports. In January 2014, the province invested $6 million dollars to community paramedicine programs providing care to the elderly. These programs have been established in a number of municipalities, including Hamilton, Toronto, Ottawa, and Renfrew County. Through the program, paramedics offer 24-hours supportive and proactive care including assessments to ensure that medications are being taken as prescribed. An evaluation of the program in Renfrew County showed the program significantly decreased emergency department utilization and delayed eventual admissions to long-term care.

Engage seniors and their families

According to Marck, seniors need to be increasingly engaged and empowered as a means of improving medication safety. Only 1 in 7 patients receive a list of medications they take from their doctor.

Some of this work can happen, according to Ghali, during a hospital admission. “Patients receive drugs in a passive way in the hospital,” he said. “They get the little miniature cups with pills in them and a glass of water. They go from being passive recipients to having to figure it out on their own when they go home. That transition is pretty unbelievable and abrupt.” He describes not educating patients in hospital as a “missed opportunity” and a potential means of mitigating the issues associated with medication safety. Ghali commented that engaging patients in hospital has been largely unexplored and provides potential new roles for allied health practitioners such as pharmacists, nurses, or nurse practitioners.

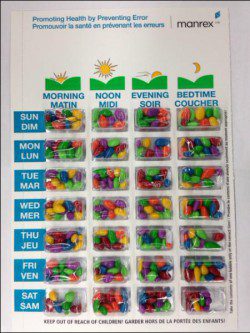

Practitioners in the home care sector are finding innovative ways to engage with the elderly and their families. At ParaMed Home Care, Reid-Haughian said nurses will create visual medication charts for their clients that include pictures of their pills and the time of day they’re expected to take them. Marck commented there are few, if any, standardized tools in home care to help clients and families understand the medications prescribed to them. Consistently implementing practical strategies, like visual charts, may be especially important in client education and improving home medication safety.

Improve communication across health care sectors

Marck says that communication across sectors is among the biggest issues to be addressed in improving medication safety at home. She strongly advocates for the development of user friendly, accessible electronic medical records that can be shared across health care sectors. Ghali noted that new electronic hospital discharge plans increasingly require physicians to identify medications that are new, discontinued, or adjusted in hospital, with rationales for the changes that were made. These discharge plans should be automatically uploaded to password-protected websites which would make updated prescription lists instantly available for patients and the community health care providers with whom they consent to share their health information. However, such systems do not exist in Canada today.

“Our system needs to be better”

Since Maria’s medications were reconciled by the community pharmacist, Mimi has felt more comfortable about her mother’s complicated medication regimen. But, according to Mimi, it took years to arrange for a health professional to review Maria’s prescriptions. Mimi went on to say, “I know my mother’s not alone. As I get older, I know my children will advocate for me the way I’ve done for my mother but our systems need to be better. We need to talk about this.”

The comments section is closed.

I ask for more people to speak up regarding this nation-wide problem so that the awareness is spread

This research was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research & Canadian Health Services Research Foundation & Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation & Canadian Patient Safety Institute & Ontario Ministry of Health-Long Term Care & Ministere de la Sante et des Services Sociaux

This article is excellent and speaks to the need to have more than the integration of these ideas. It requires mandatory legislation that outlines how professionals we be culpable by ignoring or not coordinating care for each and every patient who takes a drug. We need a policy that embraces a method to ensure patients and those that prescribe, dispense or administer drugs as well as for patients themselves who take drugs to know how to recognize side-effects, who to record the symptoms they have, and have professionals carefully monitor the patients for whom they prescribe.

I know first hand how difficult it can be for patients who take drugs that cause side effects and the problems with polypharmacy. Not one doctor that prescribed my pills recognized my problems were from the medications I’d been prescribed!

If doctors don’t understand, don’t ask, and don’t have something that outlines clearly and easily for them, & something they should be required to do: provide a systematic way to easily help them and their patients recognize the side effects their patients have, then there needs to be another group that prescribes medications. There seems to be no follow up once the medication is provided by prescription or upon refill. Whose responsibility is it? I find this a rather frightening and puzzling medication practice oversight in need of a regulatory solution.

Elizabeth Rankin