As case counts again begin to rise this winter, experts are worried that shifting evidence around COVID-19 in pregnancy – combined with misinformation about vaccination – may increase the vulnerability of this already at-risk group.

Pregnant people are at higher risk for developing severe COVID-19 illness. This is a well-established scientific fact.

But that hasn’t always been the case. Earlier in the pandemic, experts did not believe that pregnant people were at increased risk, citing no evidence of poor health outcomes in the few pregnant people who got COVID-19 initially.

But no evidence of an effect is not the same as evidence of no effect. Despite earlier confusion, there’s now substantial evidence that COVID-19 infection does have an effect during pregnancy.

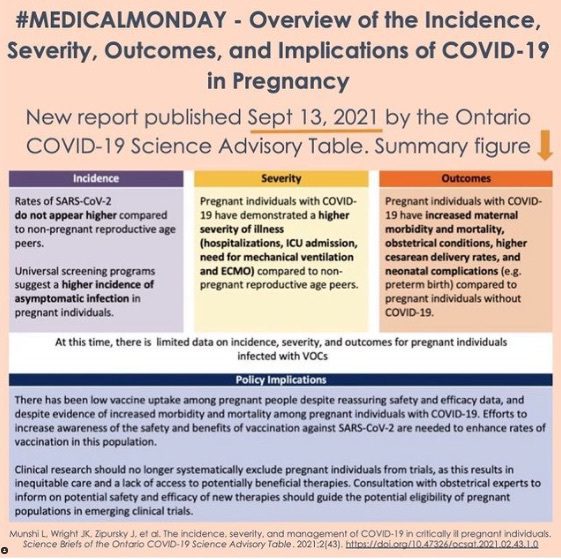

Although the overall risk is low, people who are pregnant and get sick with COVID-19, particularly those who are unvaccinated, are more likely to be hospitalized or admitted to intensive care compared to their non-pregnant peers. They are also more likely to experience poor pregnancy outcomes such as preterm birth (delivery earlier than 37 weeks), Caesarean section and preeclampsia (high blood pressure).

Evolving scientific evidence

Science is the study of uncertainty. Never has that been more apparent than during a global health crisis. Since the first emergence of this novel virus less than two years ago, we’ve seen the science evolve on mask wearing, hand washing and the spread of SARS-CoV-2 through aerosols, to name a few.

In her foreword to The Best American Science and Nature Writing 2021, Jamie Green writes: “The pandemic revealed to us, over and over, the messy, fitful work of science. Hopefully anyone who once satisfiedly intoned, ‘I believe science,’ now sees that science is not a monolith but a process.”

While scientists are used to this process of discovery, failed experiments and scientific debates, the public has struggled to keep up with rapidly changing guidelines and confusing messaging. Scientists have, at times, failed to come to a consensus and effectively communicate this uncertainty to the public.

Our current scientific dogma is one of refutation, or the act of proving something to be wrong. Rather than seek out the “truth,” scientists under a refutationist paradigm attempt to disprove a current hypothesis and generate new ones.

In statistics, the status quo (for example, that there is no difference in outcomes between two groups receiving treatment A versus treatment B) is referred to as the null hypothesis; its counterargument (that there is a difference) is called the alternative hypothesis. Under this paradigm, you can never prove the alternative hypothesis, rather you generate enough evidence to reject (or fail to reject) the null hypothesis.

This evolution of scientific evidence is best demonstrated with an example: COVID-19 in pregnancy.

Case study: COVID-19 in pregnancy

During pregnancy, bodies undergo significant changes to accommodate the developing fetus, including in respiratory function and immune suppression that make them more prone to severe infections.

Initially, scientists offered a reassuring message. They cited early studies, mostly conducted among hospitalized patients in China, that concluded the clinical characteristics of pregnant people with COVID-19 were similar to non-pregnant patients.

These studies were conducted among only a handful of people – too small to see an effect – before the surge of cases owing to more contagious variants like Alpha or Delta. They also used study designs that were inadequate to determine whether pregnant people were at increased risk compared to their same-age peers and didn’t account for the fact that pregnant people may have been taking extra precautions.

A rapid review to inform priority populations for COVID-19 vaccination in Canada conducted in June 2020 found no data specific to pregnant people; an updated review conducted in December 2020 identified only two studies. The latter found only a low level of evidence for an increased risk of hospitalization among pregnant people.

But as the pandemic dragged on and more pregnant people fell severely ill with COVID-19, more rigorous scientific studies could be done confirming that pregnant people are indeed at higher risk for maternal morbidity and mortality and adverse pregnancy outcomes, even though most develop mild to moderate illness.

Listen: The Rounds Table podcast: Episode 21 – COVID-19 and pregnancy with Dr. Kuret

“We had early reports out of China that were a bit all over the map,” says Deborah Money, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of British Columbia.

“At the beginning, we weren’t terribly alarmist because we didn’t have definitive information that it was going to be worse for pregnant women,” says Money, although she suspected it might be based on the track record of other respiratory viruses, such as SARS and MERS (relatives of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus) and influenza. “As we began to see some reports out of Europe and the United States, it started to evolve that, in fact, women were getting more severe disease.”

Money and colleagues with the CANCOVID-Preg study have since gathered surveillance data from five provinces to contextualize these findings in the Canadian population. In their latest report, they found that about 7 per cent of pregnant people aged 18 to 45 who tested positive for COVID-19 ended up in hospital compared to 1.5 per cent of their non-pregnant counterparts. Of those hospitalized, pregnant people were almost three times as likely to be admitted to the ICU.

“We’re seeing the two sides of the coin: both tougher on the mom, with more severe illness reflected in their need for hospitalization and ICU admission, and tougher on baby because of the prematurity,” says Money.

Other international researchers have come to the same conclusions.

Source: @PandemicPregnancyGuide via Instagram.

But this information for pregnant people has been slow to make its way to the public. As of early November, more than 20 months into the pandemic, the Wikipedia page on COVID-19 in pregnancy still reads: “The effect of COVID-19 infection on pregnancy is not completely known because of the lack of reliable data. If there is increased risk to pregnant women and fetuses, so far it has not been readily detectable.”

Changing guidelines: COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy

Public health decisions often must be made using the best available evidence, even if it’s incomplete. National vaccination guidelines initially advised that a COVID-19 vaccine may be offered to people who are pregnant or breastfeeding but only in certain circumstances, citing insufficient evidence on the safety or efficacy in these groups.

“There was such a paucity of evidence for pregnant populations because they weren’t included in the initial trials,” says Tali Bogler, a family doctor and chair of Family Medicine Obstetrics at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, referring to the fact that pregnant people and those planning to become pregnant were systematically excluded from the original clinical trials of COVID-19 vaccines due to hypothetical safety concerns for the developing fetus or newborn.

She co-founded the @PandemicPregnancyGuide Instagram account to support people who were pregnant during the pandemic.

“Right from the get-go, we were advocating that pregnant individuals, particularly those at high risk, should be given the choice (to get vaccinated),” says Bogler, even before studies were available to back up that message. “I know enough about vaccines to know that there would be no theoretical reason why this would be unsafe.”

Read: Prioritizing pregnant COVID patients is not altruism, it’s a necessity

The guidelines have since been updated following calls from medical groups, including the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada.

As of May 2021, the National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) started strongly recommending that pregnant and breastfeeding people should receive two doses of an mRNA vaccine (mRNA vaccines are preferred over viral vector vaccines due to the risk of vaccine-induced blood clots but may be offered when mRNA vaccines are contraindicated or inaccessible). It made that decision after reviewing real-world evidence of administering mRNA vaccines to more than 35,000 pregnant people, finding no obvious safety signals.

Science is the study of uncertainty. Never has that been more apparent than during a global health crisis.

But this changing advice comes at a cost. Vaccination rates among pregnant people remain low, with only 66 per cent fully vaccinated in Ontario compared to 78 per cent of their same-age peers without any risk conditions who have gotten both shots.

“Early in my pregnancy, there was still a lot of unknowns about the vaccine,” says Andrea Farrell, a paramedic in Toronto who gave birth to her first child in September. “There was hesitation around getting the vaccine while pregnant because obviously there was no research about that.”

The science on the safety and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in pregnant people continues to evolve. Pfizer has an ongoing clinical trial of about 4,000 pregnant people, but those results won’t be available until next year.

“We’re just beginning to see some of the nice, large, comparative epidemiological studies where you compare outcomes in a vaccinated group versus outcomes in a non-vaccinated group,” says Deshayne Fell, an associate professor of epidemiology at the University of Ottawa and scientist with the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute.

She leads the BORN Ontario study looking at the effectiveness and safety of COVID-19 vaccines during pregnancy. “Everyone is still in the process of conducting studies, particularly in countries like Canada, or a province like Ontario, where we only recommended (vaccination for pregnant people) toward the end of the third wave,” says Fell. “A lot of those people are still pregnant now, so we have to wait for those babies to be born and the data to come into the various data systems that we have.”

Of the studies that have been conducted, so far none have found any indication of increased risk of poor pregnancy outcomes, like miscarriage, in those who have been vaccinated.

Experts interviewed for this article offered the following unanimous advice for pregnant people: Get vaccinated. This guidance extends not only to people who are currently pregnant, but also their close contacts, including children 5 to 11 years old who are now eligible for vaccination in Canada.

Pregnant people say it’s a difficult decision to get vaccinated, since their decision affects not just themselves but also their babies. Many, lacking their usual prenatal support systems, have turned to friends, family members and social media as their primary sources of information.

Farrell did end up getting her COVID-19 vaccine while 15-weeks pregnant, before NACI updated its guidelines, but not right away. She says she finally made her decision after speaking with her obstetrician, who stressed the risks for severe COVID-19 infection if pregnant, and consulted reliable resources like @PandemicPregnancyGuide.

“It’s a little bit easier now,” says Farrell. “It’s easier to make the decision about how to go about your life as a pregnant person during the pandemic because more information has come to light and more recommendations are being made.”

The comments section is closed.

Science for the Age of Covid – and the Age of Complexity.

Congratulations on this very insightful piece.

Well said – well written – science changes – to include uncertainty and complexities, like never before.

This pandemic illustrates the need for a science that reflects its complex dynamics.

Stephen Hawking says he thinks that complexity science would be the science for the 21st century.

Complexity science would help us understand the complexities of Covid-19 and pregnancy.

Much has been written about this – including some writing by me – can find at Rambihar bmj.

This includes – Science, evidence and the use of the word scientific – a Letter in Lancet,

and Chaos Complexity Covid – Teaching Health Professionals Complexity – can search online.

Complexity Thinking is needed for Covid-19 and all its interactions including pregnancy.

The science base for this is Complexity Science, a new science for a new world – in the Age of Complexity and the Age of Covid.

Thanks for posting this thoughtfully written article. On the front line in health care, under pressure to help the greatest number of people in the shortest time possible, it can be easy to begin to lose touch with some of the broader context within which medicine is practiced. Errors in basic logic can subtly creep in, so that we need to be reminded of things like the fact that “no evidence of an effect is not the same as evidence of no effect”. There can also be a tendency to forget that statistics simply allow us to form warrantable expectations. The statistical likelihood of a particular condition has no physical effect on whether a given patient has the condition in question. The fact that the waiting room is full of patients with flu-like symptoms during flu season has no effect on whether the next incoming patient with similar symptoms has the flu.

This article is a welcome and well presented case study, but rather than the evolution of evidence it would be more accurate to say it’s about the creation of consensus and decision criteria.

Bias is built into the production of evidence from the moment of conception. Inclusion criteria in clinical trials are a good example. The author here writes that pregnant people were excluded from Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine trial because of “hypothetical safety concerns.” But while

safety must be an ethical concern for all participants in any trial, it’s not the primary concern of participation criteria. These ought to be inclusion-oriented — designed to ensure that the effect of an intervention is studied in a sample of everyone it plausibly might help. Often, though, they’re exclusion-oriented — designed to maximize the likelihood of obtaining a statistically significant benefit as well as the size of the demonstrated effect.

Where the intervention is a treatment, exclusion by criteria such as age, co-morbidity or reproductive status is ethically dubious. Where it’s intended as prevention for all, as in the case of vaccines, such exclusions are indefensible unless bona fide practical grounds exist — because exclusion has consequences. Approvals and recommendations are restricted, the excluded groups are slow to receive the preventive measure, and identifiable harm follows.

Whatever its validity, people use evidence in different ways; scientists and policy-makers are no exception. To build models and make forecasts, epidemiologists need to know the current state of human biology. Hospital CEOs need to manage admissions. Public health officials plan mass interventions, address expectations and try to influence behaviour. All say they’re acting on the basis of science and evidence. But they draw from other cognitive domains such as environmental scanning and role discipline, and sometimes differ markedly in their conclusions.

As for clinicians, they too project a profound respect for evidence. But infinite uncertainty and best available hypothesis make a poor response to the anxious patient. So in Dr. Tani Bolger’s practice, other sources of knowledge came into play. Of vaccination during pregnancy she says: “I know enough about vaccines to know that there would be no theoretical reason why this would be unsafe.” Well ahead of public health she offered vaccine to pregnant people despite their exclusion, on dubious grounds, from Pfizer’s vaccine trial.

What does this mean for the public appreciation of science? Well, yes, science (actually, all investigation) is the study of uncertainty. What we call evidence and facts are mostly statements of probability. What we call knowledge is a consensus ranking of hypotheses. These are difficult acknowledgments to make in a culture steeped in the notion of absolute certainty and 100% probability.

Nevertheless, scientists and clinicians have nothing to gain by being less than frank about how consensus is developed and how the gaps between statistical success and actionable knowledge are filled.