The use of masks and face coverings is considered best practice for preventing the spread of COVID-19 and numerous jurisdictions have implemented rules requiring the wearing of masks in public spaces. Ontario Premier Doug Ford is among the many who have recognized the importance of masks: “I think it’s a good thing when you are out in public, wear a mask, wear a face covering,” says Ford.

Given the benefits, and the support from the provincial government, many Ontarians may be wondering why the use of masks has not been made mandatory as yet. According to Ford, the main reason is enforcement. “… To police 14.5 million people would be very difficult,” the premier says. “We just don’t have the manpower for bylaw and police officers to be chasing people without masks.”

Ontario Minister of Health Christine Elliott has further noted, “(a) provincial policy isn’t necessary as local medical officers of health have the authority to institute the same policy under Section 22 of the Health Protection and Promotion Act. Doing so at a local level would ensure responsiveness to community needs without applying the same policy to regions with little to no COVID.”

In short, provincial legislation mandating masks has been deemed too difficult to enforce and unnecessary given the power allocated to local medical officers of health. Neither of these reasons is convincing and is a rather disappointing level of justification to download the responsibility of managing masks to regional and municipal levels.

There is no question that policing 14.5 million Ontarians is a difficult task. For one, it is not clear who would be responsible for enforcement. But challenges with enforcement have not precluded other laws from being enacted to protect individuals and the public. Speed limits, seatbelt use and bicycle helmets are among numerous laws to improve public safety and protect individuals and face similar enforcement challenges.

We have also seen other measures put into place to prevent the spread of COVID-19 that are equally difficult to enforce. Consider the mandatory 14-day isolation periods, described as difficult and requiring a “massive logistical effort.” Indeed, the enforcement of such orders has often been lacking or sporadic – but this was never considered to be a reason for not mandating the isolation period.

The enactment of laws helps to define a norm of conduct that can maximize public safety as a collective. Mandating masks does not mean that the province will have to “chase” and penalize every individual who fails to abide but it will allow the province to send a strong message to all Ontarians about the importance of masks as a preventative measure. Moreover, placing responsibility on regional and municipal governments has resulted in geographic differences.

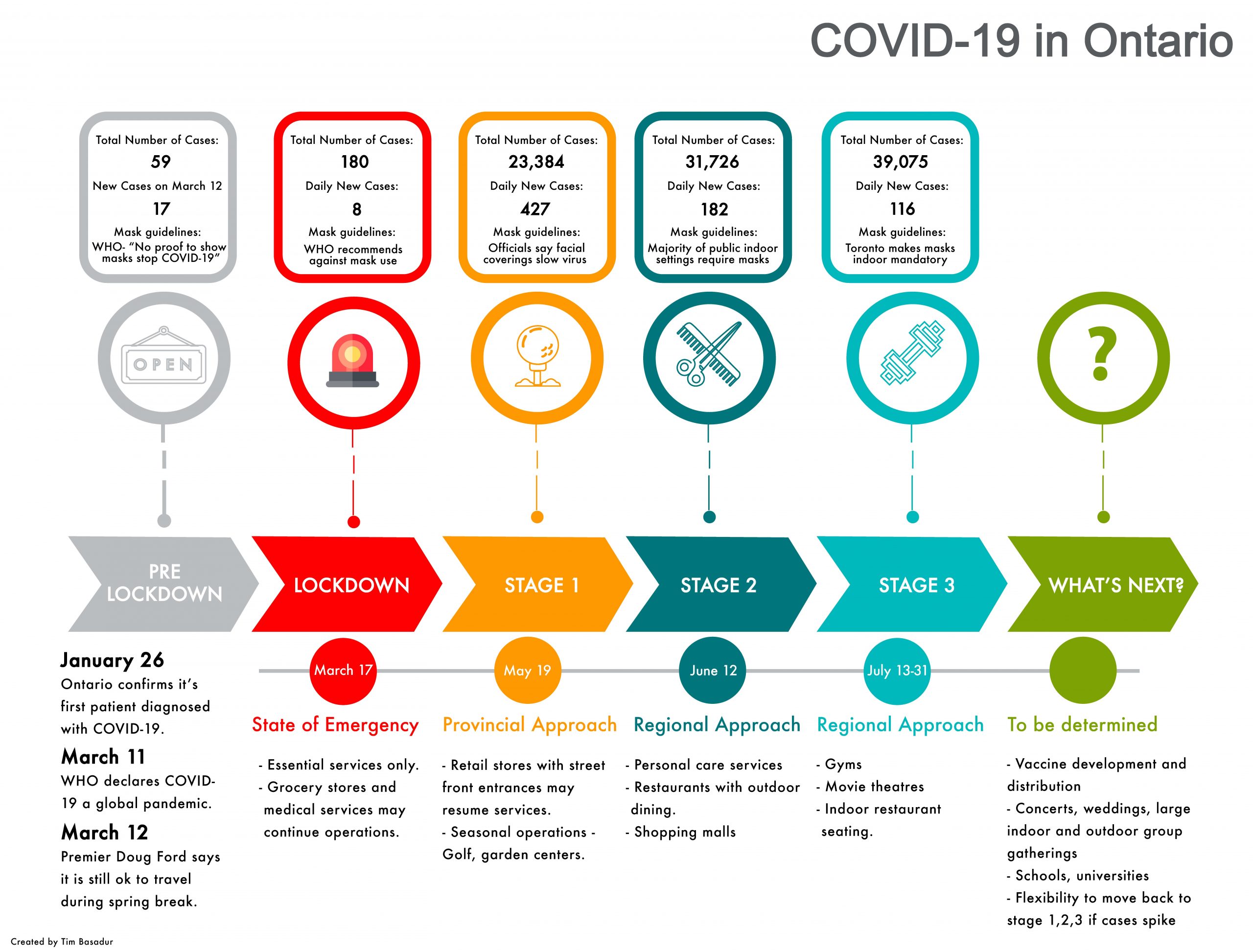

To achieve the highest level of compliance and avoid confusion among Ontarians, a law implementing mandatory masks or face coverings should apply province-wide. Of Ontario’s 34 local health authorities, 23 have to date implemented their own policies (in addition 8 have policies implemented by their municipalities, as shown in Figure 1).

However, this has resulted in a fragmented approach as local governments address the prevention transmission in different ways while moving through the Framework for Reopening. The consequence is myriad policies and approaches enacted throughout Ontario (Figure 2).

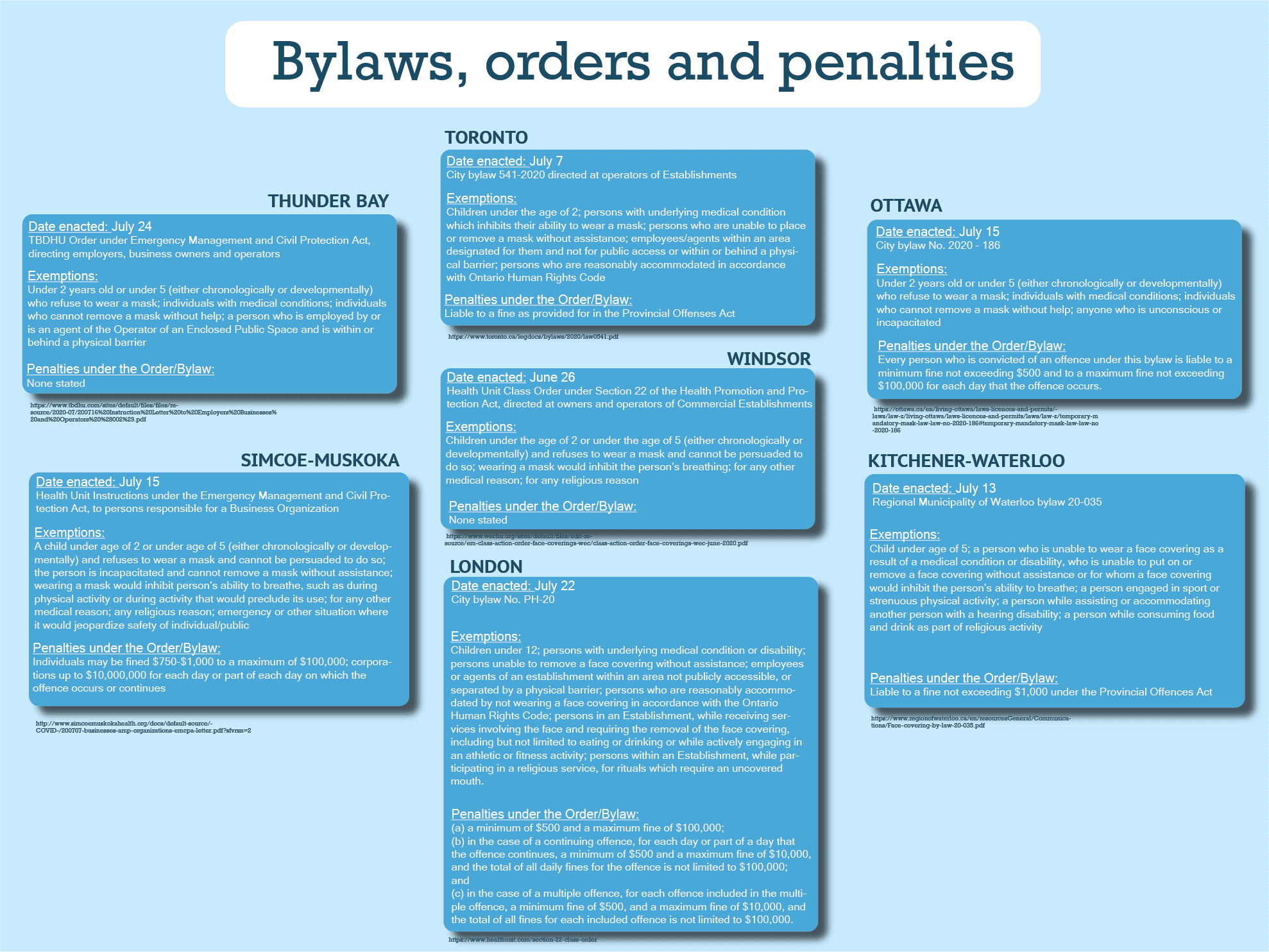

Some municipalities and regions have enacted bylaws mandating people wear masks while indoors while others

have deferred to their local health units’ recommendations and orders. Some orders are directed at businesses while others are directed at residents. Some policies carry heavy penalties, with fines up to $10,000,000 for corporations that violate the Order, while others do not state the fines or punishments that will be used should the order be enforced.

The consequence depends on where you live: in Peterborough, a fine for failing to comply cannot exceed more than $1,000 a day whereas under London’s municipal mask bylaw, one can be fined between $500 to $100,000. There are also different age exemptions: an 11-year old child may be mandated to wear a mask in many parts of Ontario but not neighbouring regions. The divergent approach has resulted in confusion.

Minister Elliot has stated that responsiveness to local community needs is a benefit to using a regional approach but this does not reflect the reality of COVID-19: it will infect people regardless of location.

Although some regions within the province have fewer cases, there is a great deal of mobility within Ontario. Prior to the pandemic, people moved throughout Ontario for a variety of reasons, including for school, travel and work. This kind of travel is always expected, and unavoidable for some. As Ontario progresses to Phase 3 in the Framework for Reopening, we will see an increase in mobility. We may also see a new type of regional travel based on the type of restrictions in place. For example, if indoor dining or hair salons are not available in one region, there is nothing preventing an individual from travelling to a region where such services are available.

Premier Ford has argued that in areas where there are no cases, we cannot tell them to wear masks. But if a region has a low infection rate and thus less restrictive mask and face-covering policies, this supports the need for a provincial law. Requiring masks would ensure that regions with low infection rates do not let their guard down and inadvertently become a hotspot for transmission – whether from local residents or from those travelling to the region.

The simplest and most cost-effective way to prevent the spread of COVID-19 is to require that all citizens wear a mask when in public. The best way to ensure that this is done consistently across the province is to implement a provincial law that mandates the use of masks in all indoor spaces and in situations where physical distancing is not possible.

There are concerns that this type of law may interfere with individual rights and protests have popped up across the country. Indeed, the Canadian Constitution Foundation (CCF) raised concerns that mandatory mask policies implemented in Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph, violated protected Charter rights, specifically Sections 7 (life, liberty and security of person) and 15 (equality). They suggest that forcing individuals to cover their faces is a violation of bodily integrity (Section 7) and that these policies have a disproportionate impact on individuals living with disabilities (Section 15). They further argue that these infringements are not justified intrusions on rights. Medical exemptions from wearing masks are not enough, they argue, as they do not consider the privacy and equality rights of individuals with physical and mental disabilities. We contend that these concerns are overstated – indeed the CCF acknowledges that mandatory mask measures can be used if carefully constructed (e.g., not requiring individuals to provide medical information to be exempt from wearing masks). Many regions currently do not include a requirement for residents to provide proof or justification for their exemption; they merely do not have to wear one and businesses have to respect this decision. Exemptions help overcome concerns about rights violations and do not diminish the effectiveness of masks as research indicates that masks are most effective when 80 per cent of the population or more complies.

While a law mandating masks may interfere with the rights of Ontarians, we hold that this interference is justified by the evidence of the efficacy of masks and face coverings when physical distancing cannot be maintained. We can limit the transmission of COVID-19 in other ways but these are more impairing. Compared to other measures, such a widespread closure of businesses and public spaces, masks are the least intrusive.

As Ontario continues to open, making physical distancing more difficult, masks are a simple measure to protect all residents, particularly those most vulnerable to this disease. Thus far, there have been high levels of compliance. For example, following the TTC’s rule requiring masks on their vehicles, 94 per cent of riders are wearing a mask, this despite the fact that the TTC had not planned on enforcing the rule.

Let’s be clear: most people don’t want to wear a mask. At the same time, nobody wants to contract or transmit COVID-19. The COVID-19 pandemic is far from over. As we open Ontario for business, we can, and should, ensure that we take measures to ensure that we limit the transmission of this virus.

It is time for Ontario to enact a mandatory mask law, even if it will be difficult to enforce. It sends a clear message to all Ontarians that we are in this together.

References: Public Health Units. Ontario Ministry of health. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/common/system/services/phu/locations.aspx#7

The comments section is closed.

No thanks. Want to wear a mask? That’s your prerogative but as a healthy person, I will not wear one for this cold.

NO!

Hi Joyce,

While it is clear that disagree with the proposition, it’d be more interesting to hear why you disagree.

Nobody wants to wear masks when indoors in public or when social distancing isn’t possible, but nobody wants to get COVID-19 either.

Many opposed seatbelts when they were first required – perhaps you still find the use of a seatbelt draconian.

Note, you can simply avoid wearing a mask by staying home.

Best,

Jacob

Yep, masks will fix all…

BTW there’s this fantastic bridge in Brooklyn that I’m willing to sell to you for a great deal

Hi Ricky,

I’m currently not shopping for bridges, but thanks for the offer.

Masks are not going to fix everything, but like bridges, they’ll help us get to where we need to go – in this case our destination is reducing transmission.

And yet there is no law requiring flu vaccination and the flu does kill many people. You are able to have the flu and wander about anywhere you want legally including long term care facilities. Once a vaccine is readily available that works well, will masks still be mandated to be worn? I believe any discussion on masks should include a discussion on vaccines to put the issues into perspective.

Hi Mike,

You’re right that the flu is dangerous. Vaccines are important. There are some that think flu vaccines should be mandatory. But that is not the current issue before us. Just because we can – and perhaps should – legislate other public health measures, the fact that we haven’t doesn’t diminish the need to find appropriate policy responses to the current pandemic.

We should also reconsider how we approach long term care facilities and the potential exposure of residents to infectious diseases.

I agree that the ability to vaccinate against COVID-19 will change our approach to masks. Until such a time, however, masks are our best line of defense as we open up society.