At every clinic and hospital, scientists work with health leaders to test health-care innovations. As you read this, researchers are trying to improve diabetes screening, develop monitoring technologies for heart attack patients and create better community mental health programs, to name just a few.

But these researchers face major hurdles. Too often, their developments don’t lead to improvements in health care. A study published in 2014 found that half of all quality improvement projects in hospitals don’t change established practice. One reason is that researchers aren’t part of teams delivering the care they’re trying to improve. They don’t understand the workflows already in place and instead try to “reinvent the wheel,” explains Noah Ivers, who led the 2014 study.

The disconnect between researchers and providers means interventions often aren’t implemented as they were designed. Screening forms don’t get filled out. Patients don’t get signed up for a new program. Says Paula Lozano, the co-director of Kaiser Permanente Washington’s Learning Health System Program: “Researchers have a reputation for showing up in the clinical setting and saying, ‘I have this wonderful training that I’m going to give to all the providers to prevent this bad outcome.’ And care teams run screaming from you because you’re not starting from what they see as their problems, and you’re not taking into account how busy they are.”

Health-care delivery involves a lot of moving parts and complex power dynamics. Changes take time. But when researchers complete their project and move on to the next, front-line providers not invested in the original program typically aren’t motivated to continue pushing it forward.

“One of the big problems I see is that the research is often produced by people who aren’t delivering the care,” says Muhammad Mamdani, Vice-President of Data Science and Advanced Analytics at Unity Health Toronto. “So, for a researcher, what’s your motivation to make sure your recommendations are adopted?”

Enter the learning health system

The learning health system is, as Ivers describes, “a long-term investment in systematic, incremental improvements.” The concept first emerged from a two-day Institutes of Medicine workshop in 2006 and was further described in a 2012 paper. But it’s still considered an emerging idea. (As you see, new ideas take time to spread).

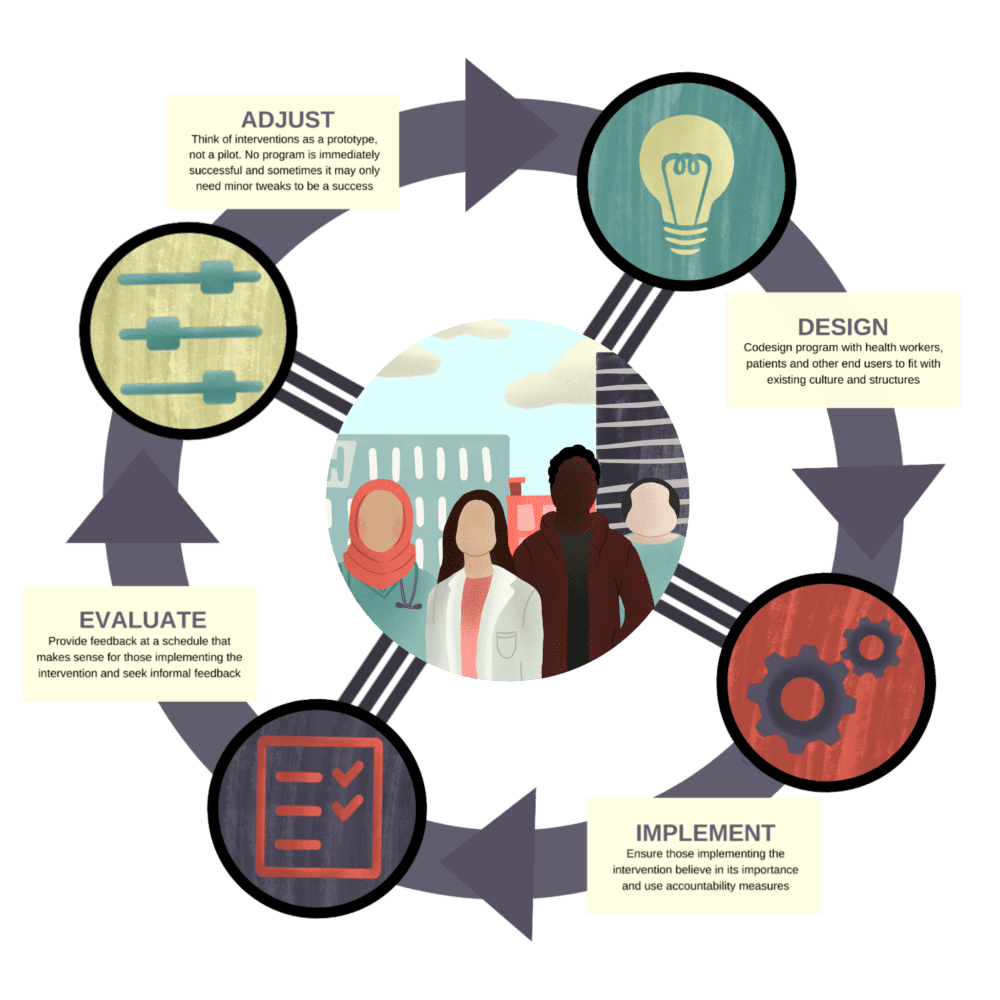

The learning system moves away from the traditional idea of independent researchers overseeing years-long randomized controlled trials and only releasing their data at the end. Instead, there’s a “vital partnership between research and clinical operations,” as the authors of the 2012 Annals of Internal Medicine paper wrote. Interventions are evaluated “in real time” and early feedback lets research and health leaders adjust the plan as they go along.

The differences between the traditional way of doing things and a learning health system starts with how problems are defined. In academic research, external scientists often decide what issue they want to focus on. In a learning health system, it’s the patients, nurses, doctors, managers and scientists embedded in the health system who work together to decide where the problems lie – and what the solutions should be.

Though widespread conversations to understand the nature of the problem are rare in Canadian health research, they’re happening more and more. “In health care, it’s almost revolutionary to say, ‘Let’s go talk to the community and see what it needs,’” jokes Ivy Wong, who is working to integrate health providers into a new Ontario Health Team (OHT) in North York.

Her OHT, taking a learning health system approach, did just that when COVID hit last spring, asking a wide range of community members about the problems they were facing. Over and over, people cited the issue as a lack of information. Which organizations were still delivering food? What social and mental health services were still running? The team used this information to implement a hotline for patients, caregivers and primary care and social workers.

The overlooked art of implementation

Too often, a perfect solution on paper doesn’t work when rolled out in a clinic or hospital. Walter Wodchis has dedicated his career to solving big, costly problems like unnecessary hospitalizations after surgery or poor management of diabetes. At first, he spent most of his time developing and evaluating solutions. Over the years, however, he realized that he’d been neglecting a key part – implementation. “We had enough failures on the evaluation side until we realized that it wasn’t that the programs weren’t well designed, it’s that the programs were actually rarely implemented as intended,” he says.

For example, one Ontario hospital aimed to provide high-risk patients with a nurse visit after the hospital. Wodchis was surprised to see that few patients were signed up for the visits. The reason: Patients had to be identified as “high-risk” to qualify and that could only happen if hospital providers filled out the risk assessment form. However, they found the process laborious and thought it should be the responsibility of community providers.

This lack of uptake illustrates the importance of measuring every step of an implementation – a key tenet of a learning health system. You don’t just design an intervention carefully, you implement it carefully, too, ensuring providers understand what they’re supposed to be doing and that various changes are monitored to make sure they’re being adopted as intended.

At Kaiser Permanente Washington, a research team implemented alcohol screening, counselling and referrals at 25 family practice clinics using this kind of careful, monitored and long-term approach. Although alcohol is a massive problem for health – contributing to cancers, liver disease, heart disease, pancreatitis and more – most patients in North America still aren’t routinely asked about alcohol consumption despite repeated efforts. Aiming to address the lack of screening and counselling conversations head on, Kaiser launched Sustained Patient-Centred Alcohol-Related Care (SPARC), a program that includes training in how to talk to patients, electronic prompts and more. To make sure all aspects of the program were implemented, “practice coaches” spent parts of six months at each clinic meeting with leaders, monitoring progress and adjusting the intervention to fit the clinic’s workflow.

“Developing those partnerships (with front-line providers) over time really helped ensure that our practices have continued to be sustained,” says Amy Lee, a research associate at Kaiser and the lead practice coach in the SPARC trial.

By working closely with all stakeholders and listening to their ideas, SPARC researchers were able to build trust and buy-in, two underestimated aspects of system change. Administrative staff, physicians, nurses, discharge planners, social workers and others have to understand why they’re being asked to do things differently. And they need to feel they have a say in shaping the solution.

Evaluating and adjusting solutions at every step

A strict adherence to science works for testing new drugs. But it doesn’t work for fixing what’s wrong with health systems. The learning health system approach doesn’t stick to rigid, one-time solutions. Interventions are flexible, perfected along the way as new information comes to light. While Ontario’s health system is famous for “pilot projects” – interventions tried out to see if they work or not – Robert Reid, the Hazel McCallion Research Chair in Learning Health Systems and Chief Scientist, Institute for Better Health (IBH), calls for a “prototype” approach. If the intervention doesn’t work, rather than abandoning it, you look at what aspects caused the intervention to fail, adjust it and try again.

The St. Michael’s Hospital Academic Family Health Team took this flexible, open-ended approach when trying to increase screening rates for breast, colorectal and cervical cancer. The team, led by Tara Kiran, a family physician at St. Michael’s and the Fidani Chair in Improvement and Innovation at the University of Toronto’s Family Medicine Department, started by mailing letters to patients explaining they were due for screening and programming a reminder for doctors that would tell them if the patient they were seeing needed screening. The approach increased screening rates to 65-70 per cent from 55-60 per cent, on par with the provincial average.

But Kiran and her team didn’t stop there. Their data was still concerning since patients in the lowest income quintile had the lowest screening rates. “We pride ourselves on being quite social justice-oriented,” she says. “That was an eye opener for us, and also a call to action.”

So Kiran and colleague Aisha Lofters co-led a qualitative study to identify the barriers for screening among low-income patients and co-design solutions. In interviews and a focus group, patients who had been overdue for cancer screening suggested phone calls instead of letters since they often change addresses and don’t always open mail perceived as unimportant. The team then used the experience to home in on another population with lagging screening, interviewing trans patients about their perspectives on screening and what might increase uptake.

It’s a textbook illustration of a learning health approach – one where the problem is identified by providers, patients and health-system data, and perfected along the way with information. That data can be from a clinic, a network of clinics, a hospital, a region or even a province. Wodchis argues the learning health system operates best at an in-between level – a hospital or group of clinics with enough resources to design, implement and evaluate changes but still small enough where those pushing for a change can work directly with those implementing it.

A more nimble approach to research is especially needed in the modern health system, where data is continually gathered, analyzed and shared. Big data and artificial intelligence create opportunities to learn on the fly, pinpointing factors that lead to bad drug reactions; patients who will benefit most from an intervention; cases in which investing in home visits reduces treatment costs; and much more.

But numbers alone aren’t enough for evaluating how well an intervention is working. Just as it’s important to tap into the insights of on-the-ground stakeholders in designing and implementing an intervention, you also need their thoughts on how it’s working. For example, Wodchis is about to evaluate Trillium Health Partner’s implementation of a system-wide electronic health record it began rolling out three years ago. With the EHR, all data for a patient – doctor’s notes, radiology reports, medications, etc. – are entered into the same system, so you can see the entire patient’s journey at once. In the evaluation, Wodchis’s team will use data to see what effect the EHR has on adverse events and medication errors. And they’ll be asking patients about how coordinated their care was as well.

The future of learning health systems

Though we don’t yet have true learning health systems in Canada, we are seeing more examples of this approach. The Canadian Institutes for Health Research increasingly requires scientists to co-design and implement improvement projects with clinical teams. In 2014, Trillium Health Partners launched an Institute for Better Health (IBH) that identifies where the hospital can improve and then implement solutions. Because IBH is part of Trillium, it’s easy for the researchers to continually collaborate with providers and health system leaders. And because IBH has steady funding, it’s not plagued by the start-and-stop nature of conventional research funding.

At the same time, the health system is being re-organized around patients. The barriers between hospitals, family doctors, social workers, personal support workers and others are breaking down. Case in point: OHTs that bring together a wide range of health system stakeholders in a given region. By ensuring everyone is at the table, problems and solutions will be more accurately identified, and the solutions will be better implemented, evaluated and adjusted when people in all parts of the system understand and agree with the new direction. But OHTs themselves need buy-in and thus “need to be supported in terms of having good access to integrated data and good access to support to be able to learn,” says Mike Green, clinical head of Family Medicine at Kingston Health Sciences Centre and Providence Care Hospital. And as Ivers points out, they need “dedicated funding” for research from the government.

As we move forward, funders of the health system and of research must work together to break down barriers to collaboration and adoption. The learning health system “is about speed, and execution. It’s not about discussion,” jokes Reid, referring to the very Canadian tradition of reports, commissions and research before action.

“We’re not just trying to do the same things better. We’re also trying to do new things, different things. But the research isn’t separate from the health-care system. It’s entwined. And it’s embedded in a system from the start, not at the end.”

This is the first piece in our series about learning health systems produced in partnership with the Ontario SPOR Support Unit (OSSU). A learning health system, designed for continuous iteration and improvement, is a means to make meaningful change in the way we do things in health care.

The comments section is closed.

Great article, but patients need to be seen as equal partners. How you see the other “systems” (i.e. not just the health care system) that impact health being integrated into a LHS?

How you see the other “systems” (i.e. not just the health care system) that impact health being integrated into a LHS?

Your article is well written and outlines lots of good suggestions. I’d like to add one more. “Include Patients!”

Patients are a terrific source of information but are often excluded in articles like yours. Not all would feel they could contribute, but then you never know! Much of the research we see ignores the most relevant source for untapped information.

The models for most research today still ignores the patient voice.

I would be happy to donate a book I self-published in 2015. THE PATIENTS’ TIME HAS COME: LISTENING TO PATIENTS WILL REDEFINE HEALTH CARE SAFETY AND REVITALIZE SERVICE DELIVERY. This book addresses many points you raise, and provides many solutions you might find helpful.

erankinbscn@gmail.com