The deaths of two Inuit teenagers, aged 14 and 15, in the past two years brought the tragic reality of endemic tuberculosis in Inuit Nunangat, the traditional Inuit territories spanning four provinces and territories, into the Canadian and international spotlight. These deaths of otherwise vibrant and healthy young people inspired outrage at the ongoing failure to prevent tuberculosis in Canada’s North.

Tuberculosis has afflicted Inuit populations since it first arrived via colonizers centuries ago and has continued to affect Inuit peoples in Canada disproportionately ever since. In the 1930s and ’40s, the death rate of tuberculosis in Inuit populations was above 700 per 100,000 cases, one of the highest rates ever reported. At present, Inuit peoples have a rate of new tuberculosis cases 296 times higher than Canadian-born non-Indigenous populations.

Motivated by the recent tragedies, this past December the Canadian government and Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK), the organization representing Canada’s 65,000 Inuit, announced the first stage of their plan to eradicate tuberculosis in Inuit communities: the Inuit Tuberculosis Elimination Framework.

The framework follows a commitment made by the federal government and ITK last March to halve TB cases in Inuit Nunangat by 2025 and to eradicate the disease by 2030. The government has allocated $27.5 million over five years in their 2018 budget for disease prevention, screening, diagnosis and treatment.

This new strategy looks to improve on past failed tuberculosis interventions in Inuit Nunangat, by bringing Inuit peoples to the centre of the planning and by addressing social determinants of health.

“Canada’s neglect in TB prevention and care for Inuit, both past and present, is part of the story of colonization in this country and contributes to the continued propagation of this disease,” Jane Philpott, then-federal Minister of Indigenous Services, and Natan Obed, President of ITK, wrote in an op-ed published at the time of their announcement. “Indifference towards Inuit communities is unconscionable. Canada’s response to TB must be community-owned, community-driven and adequately resourced.”

How has tuberculosis been treated in the past?

Tuberculosis is a bacterial disease most often affecting the lungs, which spreads via airborne droplets released from coughing and sneezing. Prevention focuses on adequate housing with appropriate ventilation, early diagnosis and treatment and other infection control procedures. Tuberculosis is curable with a long course of antimicrobial medications, but remains a major cause of death worldwide. The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates 10 million people contracted the disease in 2017, resulting in 1.6 million deaths.

The WHO describes tuberculosis as a disease of social inequity, disproportionately affecting those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds with poor access to appropriate housing and health care. Tuberculosis has remained in Inuit communities in Canada due to this persistent social inequity, as well as a failure of past interventions to address root causes. Epidemics of the mid-20th century resulted in at least one-third of the Inuit population being infected with tuberculosis. In response, the Canadian government forcibly relocated thousands of Inuit to southern provinces for treatment at hospitals and sanitoriums for an average duration of two-and-a-half years. In the mid-1950s, one of every seven Inuit was in a hospital in the south for treatment.

“[Inuit] diagnosed with TB would be separated from their families and had very little time to say goodbye or wrap up their affairs,” explains Tom Wong, Chief Medical Officer of Public Health and Executive Director at the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch at Indigenous Services Canada. “Then they were transferred down south for treatment, sometimes for months or years.”

The families of those who died of TB were often not notified. The Qikiqtani Truth Commission highlighted this in its 2013 report on health care: “Inuit with family members who died down south are still hurting from never having had the proper closure that could come from knowing where their relatives are buried or being given the opportunity to visit the graves.”

Tuberculosis management in the 1970s shifted to mass testing and treatment in Inuit communities. Testing and treatment were integrated into routine programs at northern health centres and provided by health care practitioners from the south. These interventions resulted in a decrease in the number of people with newly diagnosed TB, though periodic community outbreaks continued to occur. Still, by the mid-1990s, rates of new tuberculosis had fallen drastically to 31 cases per 100,000 population, down from estimates of 1,500 to 2,900 cases per 100,000 in the 1950s.

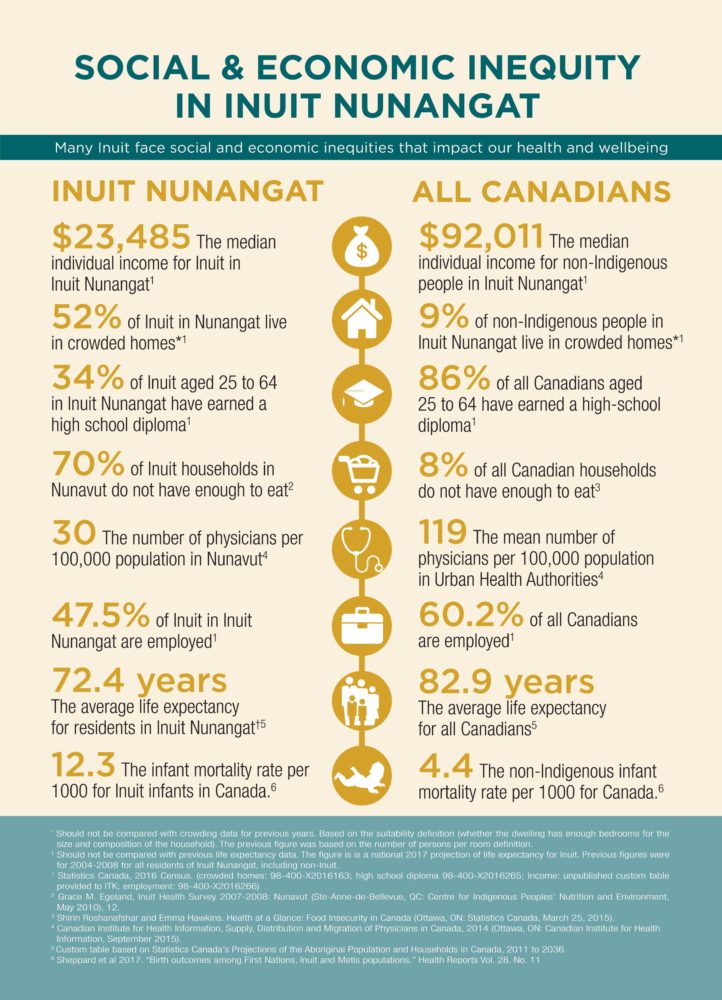

Though disease rates declined, adverse social determinants of health persisted in Inuit Nunangat, including inadequate housing, food insecurity, poor mental wellness, and limited access to health services. These factors, in combination with the failure of programs to keep the pace needed for early identification of disease and treatment of cases and their contacts, created opportune environments for tuberculosis outbreaks and resulted in the endemicity of tuberculosis in Inuit Nunangat, where disease rates are returning to levels seen prior to the successes of the 1990s.

Infographic by Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami

The new framework and what makes it different

The Inuit Tuberculosis Elimination Framework highlights six priority areas: enhancing TB care and prevention programming; reducing poverty, improving social determinants of health and creating social equity; empowering and mobilizing communities; strengthening TB care and prevention capacity; developing and implementing Inuit-specific solutions; and ensuring accountability for TB elimination.

The $27.5 million over five years that has been allocated by government will be distributed to each of the four regions which make up Inuit Nunangat: Inuvialuit Settlement Region in the Northwest Territories and Yukon, Nunavut, Nunavik in northern Quebec, and Nunatsiavut in northern Labrador.

“[Inuit] regional organizations are developing the regional action plans,” says Deborah Van Dyk, Senior Policy Advisor at ITK. These are expected to be completed by March 2019, and funding will then be dispersed by ITK to the regions, once costing for the action plans has been completed.

When asked what the framework’s priorities will look like in practice, Van Dyk explains that the framework provides an overall road map. “The specifics of enhancing TB care and prevention programming are going to be part of the regional action plans. How each region is going to look at that priority area and build up their own programs may look different.”

Regarding the government commitment of $27.5 million, Wong explains that government worked with Inuit partners to identify gaps in addressing TB (aside from social determinants of health) to determine the amount to allocate. “We have been informed specifically about the need for early diagnosis, early treatment, and supports for adherence to medications.”

Details on how each of the priorities will be achieved have not yet been released, leaving regions with flexibility. “The different Inuit regions are looking at individual needs in order to tailor the best way to have more capacity to help eliminate TB,” Wong describes. He explains that it is not only about more nurses and doctors and more advanced technology and equipment, but also about having more trained community workers and local champions to take the lead and sit down with communities to explain tuberculosis.

Will it work?

Stakeholders Healthy Debate spoke to are hopeful regarding the framework. It is considered much needed and an improvement from past TB interventions.

“[The framework] is Inuit-driven, and that’s what makes it quite different from anything that has been worked on in the past,” says Van Dyk. “[It] is shifting the focus from control to actual TB elimination. [It] is moving beyond a medical model and also looking at the social determinants of health that are driving the issue of TB in Inuit communities.”

Sylvia Doody, Director for Health Services with the Nunatsiavut Government Department of Health and Social Development, explains that the region has been doing a lot of community work and engagement in the past year as a result of an outbreak in Nain, Labrador, in 2018, which tragically left a 14-year-old dead. Lessons learned and a better understanding of the needs of the community will be used to develop their regional plan.

Doody explains that communities in Nunatsiavut are remote and isolated, fly-in only for most of the year. “We want to have TB care as close to home as possible,” she says. “Our communities do not have capabilities around equipment such as chest X-ray. Community members are often flown to the nearest site to receive those services.”

Since the outbreak last year, Nain has received a portable chest X-ray unit on loan from the Public Health Agency of Canada. “We have heard from the community since we have had the portable unit in Nain how convenient it has been for people to go to local health centres and have their chest X-ray done,” she says. “There are all those hidden costs that [people in bigger centres] don’t even think about, that [are taken] for granted because [people] can just go to the local hospital to receive services.”

Doody says the new framework “is written based on our priorities and what we see as areas for action to see elimination of TB by 2030 in our regions. It is written with a context of having the Inuit priorities at the centre and what we need to see.” She highlights addressing social determinants of health and increasing capacity—both human resource and equipment—as the Inuit-specific solutions her region is considering for TB elimination.

However, there could be some challenges to disease eradication.

Stigma and suspicion around tuberculosis interventions have been a major barrier to past interventions. Wong acknowledges that this is due to the harsh treatment and forced relocation of Inuit in the mid-20th century. “It really is a big issue. Individuals worry about ‘What will happen to me when I am diagnosed with TB? Will I be taken away from the community?’” He is hopeful that modern approaches that engage local community members will be the solution but appreciates that “for community members who are still afraid of TB, they may not actually be very clear about the current situation with TB diagnosis and TB treatment.”

Furthermore, there is consensus that the allocation of $27.5 million over five years, which Van Dyk calls “an initial contribution,” may need to be revisited in the future. Doody and Wong both agree that it’s too early to determine the need for additional funding, leaving the door open for future consideration of additional funding.

Though regions will be using the initial TB funding in part to address social determinants of health in their communities, broader funding strategies and frameworks are needed on a national level to address these issues. At present, there is uncertainty on where this necessary additional funding will come from.

Wong highlights inadequate housing, poverty and food insecurity as major barriers to tuberculosis eradication. Though he emphasizes the federal government’s announcement of $640 million dollars cumulatively over the past two budget cycles to address inadequate housing in Inuit Nunangat, he understands that government may play a role in ensuring funding to address other social determinants in the future. “We would advocate and work with our Indigenous partners to bring issues such as food insecurity to the table, or with a poverty reduction strategy.”

Van Dyk explains that in addition to the funding and framework for tuberculosis, there is a framework to be released in the coming months to complement the already announced funding for Inuit housing. She also notes that ITK is working with government to determine a strategy for food insecurity in Inuit Nunangat.

“It is imperative for [government] to support Inuit communities in their efforts to eliminate TB in Inuit Nunangat and also in addressing other factors that contribute to the spread of the disease, including inadequate housing, food insecurity, and poverty,” says Wong. “When you have efforts being led by the Inuit peoples, by the communities themselves, that is the secret to success.”

The comments section is closed.

along with money, they will need a solid plan to how to use to eradicate TB along with poverty, food shortage, shelter, etc. and proper hygiene like clean drinking water and all will also help to eradicate TB

I saw a documentary that highlighted testing issues. I believe the young girl was in critical condition before they confirmed that she had TB. The clinics should be provided with the latest and the best: “While microscopy and culture continue to be indispensible for laboratory diagnosis of tuberculosis, the range of several molecular diagnostic tests, including the nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) and whole-genome sequencing (WGS), have expanded tremendously. They are becoming more accessible not only for detection and identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex in clinical specimens, but now extend to diagnosing multi-drug resistant strains. Molecular diagnostic tests provide timely results useful for high-quality patient care, low contamination risk, and ease of performance and speed.” https://pneumonia.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s41479-018-0049-2

Is TB a reflection of social conditions? If so, it doesn’t seem that money alone will change that. We sometimes talk around those affected by a problem as if we know what they need. Detecting and Treating TB will help reduce that. To eradicate TB, people need opportunity to be vibrant, creative, individuals with an opportunity to build a strong community. That isn’t about money. It’s about vision, drive and a belief it can be done. Immigrant seeks these opportunities in other locations. Others stay and find a way to improve what they have. Individuals, decide what is best for them. The statistics- what do they reflect?