Question: I use an app to track my period. It told me I have a moderate to high risk of having PCOS. This really scares me because I’m trying to get pregnant and I’ve heard PCOS causes infertility. Should I trust the diagnosis from this app?

Answer: Flo and Clue are two of the most popular period-tracking apps available today; Flo has more than 30 million active monthly users, Clue has more than 12 million. More women than ever before are tracking their periods online.

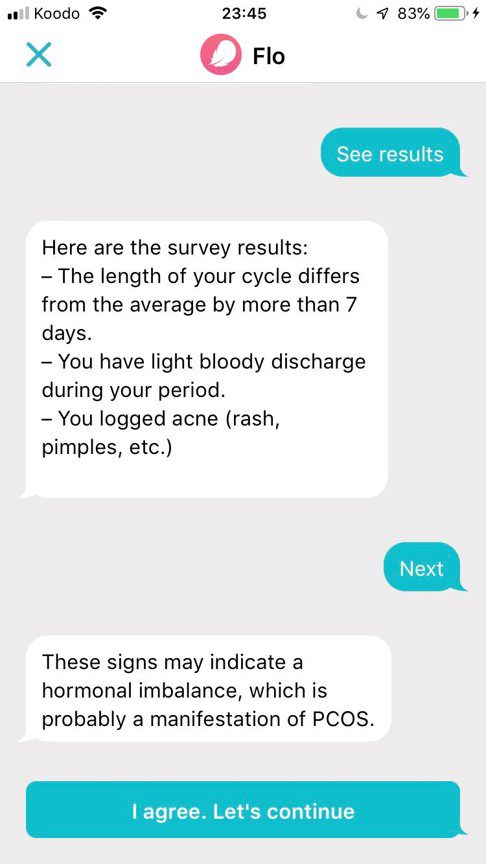

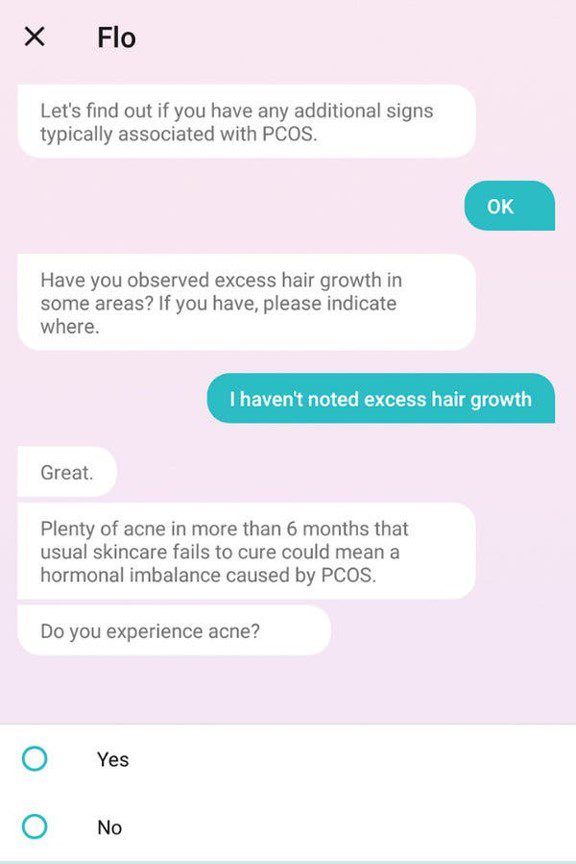

Recently, both Flo and Clue, launched new health tools that used the data inputted by users to evaluate their risk of having polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), a common hormonal imbalance. Flo described its service in a news release as a tool “to help women discover if they have PCOS and also bring peace of mind to others who may suspect they have it.”

Recently, both Flo and Clue, launched new health tools that used the data inputted by users to evaluate their risk of having polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), a common hormonal imbalance. Flo described its service in a news release as a tool “to help women discover if they have PCOS and also bring peace of mind to others who may suspect they have it.”

However, neither app has conducted high-level clinical studies and some experts are concerned about the accuracy of information being provided and whether these predictions are creating unnecessary concern among users. They warn users should proceed with caution when getting medical advice from an app, especially for PCOS, which can be a complex diagnosis to make from simple algorithms.

Yolanda Kirkham, assistant professor at the University of Toronto and an obstetrician/gynecologist, says period tracking is very important for women’s health. It allows women to understand their cycle, track ovulation when trying to become pregnant and can signal an irregularity such as multiple missed periods.

But now period-tracking apps are taking things further, from simply collecting health data to analyzing and medicalizing that data for users and making diagnoses. This is a trend within the health apps sector, in which apps for tracking health data such as sleep, mood, heart rate and electrocardiogram (ECG) information are now predicting health issues, including possible heart conditions. Most of these apps have not conducted high-level research on their outcomes. Or considered the potential for unintended consequences such as overdiagnosis.

Kirkham says “there is a danger in artificial intelligence giving medical advice,” because “these apps do not look at the patient as a whole or ask the correct questions to help get a diagnosis.” Which is why gynecologists, including Kirkham, are suggesting women specifically concerned about PCOS should consult a doctor before using the internet to self-diagnose.

This is because many misperceptions exist about PCOS despite its widespread prevalence. Estimates vary widely, but most experts agree around 10 per cent of women have PCOS.

PCOS disturbs the ovulation process, meaning what is supposed to be a monthly release of an egg from an ovary is either not happening or happening infrequently – so there is no trigger to menstrua te. Estrogen is changed over to male sex hormones, which results in an excess of androgens.

te. Estrogen is changed over to male sex hormones, which results in an excess of androgens.

Besides irregular periods, women with PCOS may experience things like acne, excessive hair growth and enlarged ovaries.

Women with PCOS are four times more likely to get diabetes, says Jamie Benham, an internal medicine specialist at the University of Calgary whose research focuses on PCOS. They can also develop heart and vascular disease, high blood pressure and sleep apnea. Benham says PCOS is also linked to increased depression and anxiety.

Because of the real health risks connected to PCOS, Kirkham and Benham agree that more information on PCOS is needed to counter the misperceptions and ultimately benefit women’s health. That’s why they don’t oppose the idea of period tracking apps providing information to women about PCOS, but a formal “diagnosis should always come from your doctor,” says Kirkham.

Diagnosing PCOS is not always a straightforward process. Kirkham says the first step she takes is to rule out more serious conditions, including primary ovarian insufficiency, a form of early menopause, and thyroid dysfunction. Both of them can be detected with a blood test.

Alternatively, there might be an underlying eating disorder; many underweight women frequently miss periods or stop menstruating all together.

Once other causes are ruled out, Kirkham uses the Rotterdam criteria to diagnose PCOS. A patient must present with at least two of three symptoms: missing periods, androgenic symptoms (acne and hair growth) or bloodwork, and polycystic ovaries on an ultrasound.

“I think some doctors may not understand that if a patient has polycystic-looking ovaries, it does not always mean a diagnosis of PCOS,” says Kirkham. “The name is a little bit deceptive because every woman has cysts on their ovaries at all times.”

Some women are diagnosed as teenagers, while others don’t find out they have PCOS until much later in life or when they have difficulty getting pregnant. Many of the symptoms for PCOS mimic common puberty changes, says Kirkham, which is why she generally waits to diagnose PCOS in teenagers.

Infertility tends to be the largest concern for women diagnosed with PCOS, but most people are unaware that PCOS is not directly correlated with infertility. Benham says it “does not directly impact a women’s ability to become pregnant.”

Kirkham likes to use the term “sub-fertility” instead of infertility for her PCOS patients. While up to 70 per cent of women with PCOS may have difficulties becoming pregnant, it is unknown how severe these difficulties are. For instance, we don’t know how many of them need to use in vitro fertilization (IVF) to become pregnant.

“I want to make sure my patients are not just hearing ‘You’ll never have babies’ because that’s almost never true unless that person has another fertility issue,” says Kirkham. Sometimes it’s as simple as getting an injection to induce ovulation for women with PCOS to become pregnant. Others can become pregnant without any assistance.

Another major concern women have about PCOS is its connection to endometrial cancer. This is because women who do not have regular periods build up a thick uterine lining, which can lead to a condition called endometrial hyperplasia and can eventually lead to endometrial cancer. “This doesn’t happen very quickly,” says Kirkham. “It can happen over decades if untreated.”

Treatment for PCOS varies. “For example, some young women find acne and extra hair most bothersome,” says Kirkham, who says she would treat this with a birth control pill to balance a women’s hormones.

To protect against uterine build-up, and the risk of uterine cancer, a dose of progesterone can be given to a patient to balance the excess of estrogen and prompt a regular period without birth control. Alternatively, a progestin intrauterine device (IUD) can also protect against endometrial cancer.

For women with PCOS who are overweight, lifestyle changes are recommended, including exercise and nutritional changes, as they can reverse the symptoms.

As people are becoming more aware of PCOS, how it presents and its health implications, Benham says more research is needed because “there is still a lot we don’t know.” What we do know, however, is that “this is a syndrome, not a disease,” says Kirkham, and it is very treatable.

Period-tracking apps should be cautious when informing women about their risk of PCOS, because this syndrome is often misunderstood and can cause unnecessary fear, especially among otherwise healthy young women. That’s why, for now, a diagnosis for PCOS should come from your doctor and not your phone.

The comments section is closed.