In early March, Dr. Benjamin Fine, a radiologist at Trillium Health Partners, searched the Ontario government website for the number of COVID-19 cases and found a static table with no visuals or ability to search the previous day’s numbers.

In his view, one of two stories was playing out: “The government didn’t know what was going on. Or the government didn’t want us to know what’s going on,” he says.

“Both are scary.”

The realization has inspired #HowsMyFlattening, a team of 150 contributing computer scientists, epidemiologists and public health experts that aggregate Ontario-specific pandemic data. They analyze mobility, ICU beds, testing rates and hospital capacities to better understand how these elements impact Ontarians’ health.

“Our numbers say we’re not really trying to eliminate the disease,” says Fine, who is also an affiliate healthcare engineer at the University of Toronto. It’s more of a “‘slow-burn plateau.’”

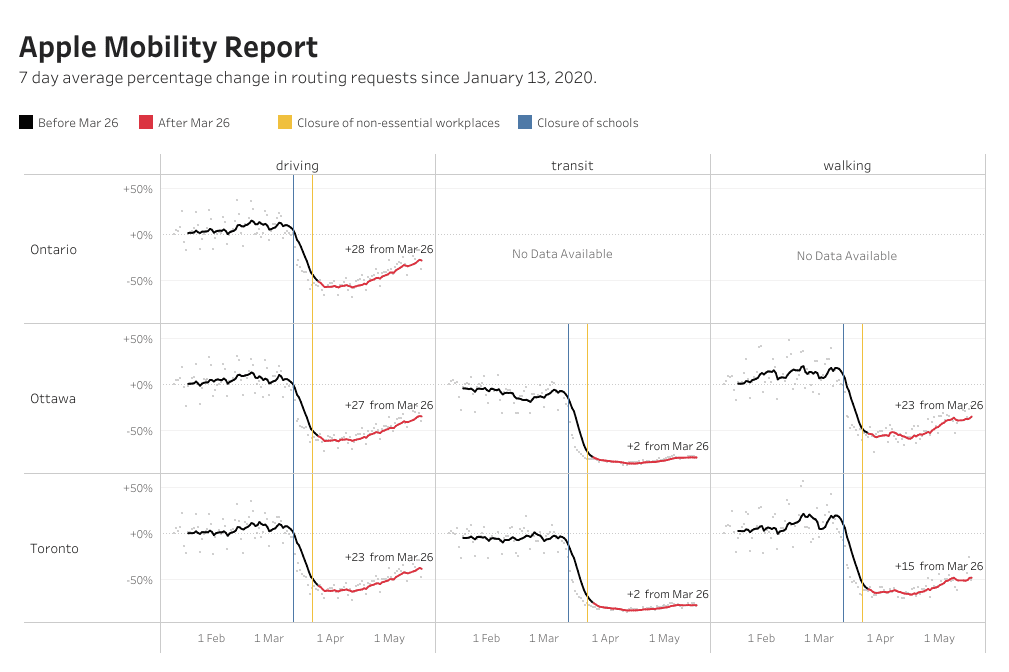

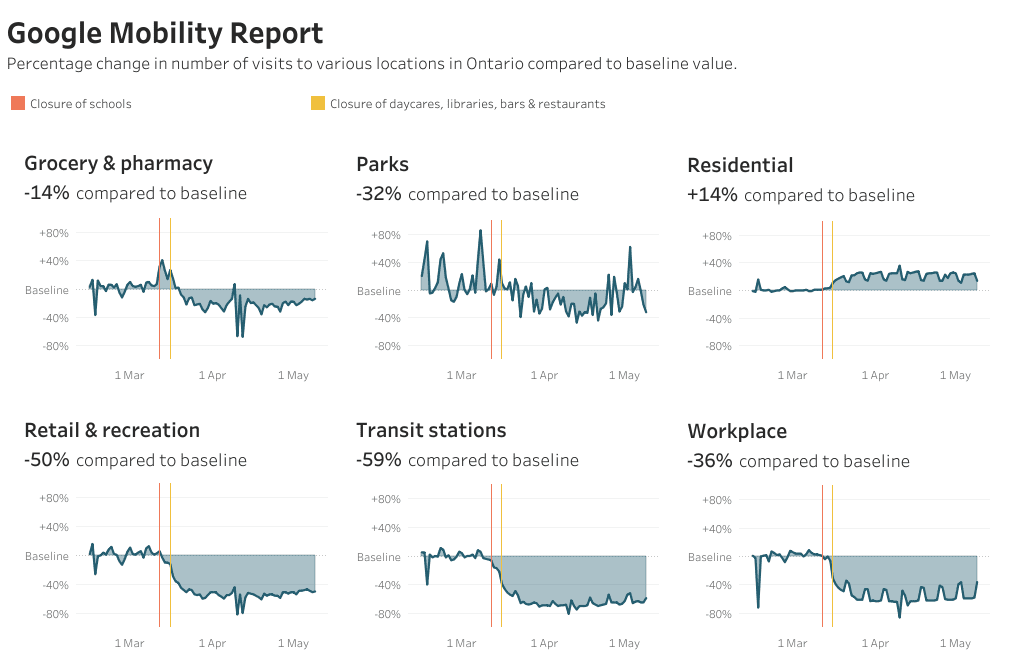

As the weather warms up and the city begins to re-open, Apple and Google data analyses of mobility on #HowsMyFlattening show Torontonians are driving and walking about 20 per cent more than they were two months ago. Apple and Google data analyses on #HowsMyFlattening compares daily mobility to pre-social distancing measures. Transit numbers, however, are still 59 per cent below the baseline volume on January 13.

“Our actions today impact the curve in about 14 days. The question is what will the data look like in a couple of weeks?” Fine asks.

Apple and Google have both been posting community mobility data daily throughout the pandemic — reflecting direction queries entered into Apple Maps and Google visits — to chart movement trends over time by country or region. The data does not publicly link to individuals. Instead, Google posts the total number of visits that fall into large location categories, including retail and recreation, groceries and pharmacies, parks, transit stations, workplaces and residential.

The data shows that more people in Ontario are visiting parks on Google on hotter days. On May 3, it was 22°C in Toronto — the hottest day in the city since quarantine began — and park queries on Google increased 62 per cent compared to the pre-pandemic baseline (the median value, for the corresponding day of the week, during a five-week period from Jan. 3 to Feb. 6).

Since the baseline was in winter, people are naturally outside more now. But even when May 3 is compared to a prior weekend in April, the increase in visits is significant: On April 25, it was 12°C in Toronto and parks queries were up 22 per cent — 40 per cent below the May spike.

Data from the Victoria Day long weekend is not yet available, but public health experts are concerned about the increase in mobility that the warm weather brings.

“If you want to understand the impact of the long weekend, you have to wait two weeks and also take into account how much we are testing over those two weeks,” says Vinyas Harish, a core member of the #HowsMyFlattening team and an MD, PhD student in the Faculty of Medicine and the Dalla Lana School of Public Health at the University of Toronto.

Layered on top of this two-week lag, patients who have COVID-19 symptoms may report them on different days, making it difficult to link to the day of contraction. There is also the invisible number of asymptomatic cases that cannot be traced without a significant increase in testing.

“We are certainly underestimating the burden of disease that is out there,” says Fine. Without testing hundreds of thousands of Ontarians a day, he says, the number of cases is undoubtedly low-balled. In reality, the lab capacity of COVID-19 testing in the province is only 19,000 a day.

Surveying movement is just one piece of understanding how shifting dynamics impact the pandemic puzzle and, in turn, the health of Ontarians. For Laura Rosella, co-founder of #HowsMyFlattening, an epidemiologist, associate professor in the Dalla Lana School of Public Health and director of the Population Health Analytics Lab at the University of Toronto, this type of analysis ensures policy responses are effectively controlling the disease and taking into account the full picture of the pandemic.

“The problem with infectious diseases,” Rosella says, “is if you only respond to pieces (of the population), it’s going to get out of control. You either have to have a holistic way of looking at the whole population and blind spots, or it’s going to continue to burn.”

The comments section is closed.