As COVID-19 spread across the world early this year, Drs. Darren Yuen and Kieran McIntyre watched with mounting concern as reports out of China showed lung scarring and lingering breathing problems in supposedly recovered patients.

The doctors, who work at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, knew that they too would soon beseeing people with breathing complications. So McIntyre, a respirologist, and Yuen, an expert in organ scarring, decided to try out a bedside ultrasound tool to quickly diagnose lung scarring. They also began working together to test a new drug to block COVID-19-induced lung damage.

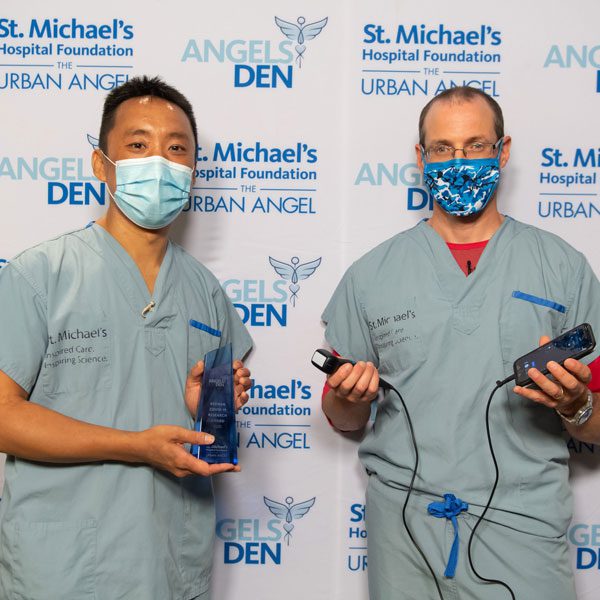

On Wednesday evening, St. Michael’s Hospital Foundation announced the pair won the $150,000 Keenan COVID-19 Research Award at its sixth annual medical research competition, Angels Den. A second $150,000 prize, the Odette Innovative Health Award, went to St. Michael’s Dr. Karen Cross for new technology to prevent pressure wounds, a painful and life-threatening condition.

This year’s competition – virtual, due to COVID-19 – was presided over by a panel of three celebrity judges – retail, fashion and business pioneer Joe Mimran, tech entrepreneur Michele Romanow and producer and content creator Vinay Vermani. Six teams of finalists made up of doctors and scientists from St. Michael’s Hospital, part of the Unity Health Toronto hospital network, had four minutes each to pitch their research.

Yuen and McIntyre recognized early on that assessing lung damage in COVID-19 patients using CT scanners – the gold standard for diagnosing organ scarring – would be a slow, expensive undertaking.

“It requires proper safety protocols,” says Yuen. “You not only have to wipe down the machine but the whole room. It really slows things down.”

They bought five hand-held ultrasound scanners to test at patient bedsides. The devices, about the size of a large cellphone, plug into a standard smartphone, allowing doctors to see the scan on their screen and make an immediate diagnosis.

Not only can the portable scanners be easily cleaned and moved from room to room, they cost just $3,500 each as opposed to the $2-million price tag for a CT machine. The doctors are now comparing the hand-held devices’ scans to CT scans to ensure their accuracy.

If they find they can rely on the ultrasound devices, they may be able rule out the need for follow-up CT scans. “We are in the process of exploring who does and does not require a CT scan,” says McIntyre. That’s important because the machines are in high demand for diagnosing a range of ailments.

Yuen and McIntyre are also testing a drug that showed early promise in lab-based studies, blocking scarring before it begins. While there are medications and therapies to help ease symptoms, scarring can’t be repaired.

Yuen, who is also a researcher at the Keenan Research Centre for Biomedical Science, developed the drug for kidney scarring but says it could be used for other organs.

“We had just started preliminary testing on lungs in early 2020 but we got shut down with COVID, as did many research projects,” says Yuen. He is now back in the lab and expects the award money will help him further prove the medication so it can move to human clinical trials.

Cross also intends to use her cash prize to get her device for assessing the risk of pressure wounds – or bed sores – into clinical trials.

Cross also intends to use her cash prize to get her device for assessing the risk of pressure wounds – or bed sores – into clinical trials.

“Most people think of pressure wounds as something you put a Band-Aid on and it gets better,” says Cross, a plastic surgeon and researcher at the Keenan Research Centre for Biomedical Science.

“But your skin, fat and muscles are eroding, creating fairly big holes,” she says. “At times, I’ve been able to put my full arm down someone’s back or leg.”

About 26 per cent of patients in Canada have pressure injuries, one of the highest rates in the world, says Cross. That’s largely because it’s not taken as seriously here as it is in other countries and while the solution sounds simple, it isn’t.

The solution of course, is to change patients’ positions so they don’t have sustained pressure in one area. But this is often easier said than done in busy hospital wards and care facilities. It can take several staff to safely move patients on ventilators or patients who are paralyzed, elderly or frail.

Working with a team of software engineers and wound care specialists, Cross created a palm-sized device that attaches to a smartphone, turning it into a deep tissue imaging system. The device, called SkIP (short for Skin Imaging for Pressure Injuries), determines the patient’s risk profile for pressure injuries.

SkIP recommends the next steps for monitoring and treatment so that non-experts can intervene early. SkIP is also interactive, allowing for collaboration between different healthcare providers to ensure optimal treatment.

Cross says COVID-19 has made these wounds an even more urgent problem. Not only are some patients spending more time in one position on ventilators, the extra stress on the healthcare system leaves less time to monitor other patients for pressure wounds. As a result, more patients are seeing their wounds spread, leading to sepsis – a life-threatening response to severe infection.

In 10 years, she had never sent a single patient to palliative care. “In one day, I sent three people to palliative care for a hole that was so large it couldn’t be treated,” says Cross. “This is very personal for me. I didn’t become a doctor so I could send people to die.”

Which is why the award is especially important to her. Not only will it help her commercialize SkIP, it will help people understand how serious these wounds can be.

“It’s about showing that this is a priority and giving a voice to these patients who haven’t had a voice up to now,” she says.

Other finalists:

The top prize winners at Angels Den were up against some impressive competition. Both winning research teams were at pains to praise their colleagues’ projects, with other finalists receiving $25,000 and the People’s Choice Award decided by viewers worth $50,000.

As McIntyre put it, “Any one of them could have been chosen and it would have been the right choice.”

People’s Choice Award

Dr. Jane Batt, Scientist, Keenan Research Centre for Biomedical Science, and Respirologist, St. Michael’s Hospital

The challenge: People who are critically ill often see their muscles waste away. While the condition might just be prevented with neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES), the current technology is practically and economically unfeasible.

The solution: Invent “smart textile” garments, like leg stockings and arm sleeves, that automate NMES through the power of AI.

The T-cell vaccine vs. COVID-19

Dr. Mario Ostrowski, Scientist, Keenan Research Centre for Biomedical Science, and Infectious Disease Clinician, St. Michael’s Hospital

The challenge: COVID-19 vaccines currently being developed are using only antibodies to fight the virus, which may mean multiple vaccine doses. And none of them are being created in Canada.

The solution: Create a Canadian-made vaccine, the first in the world to use both antibodies and T-cells to develop immunity.

Gemini: Digital tools to prepare for the second wave

Dr. Amol Verma, Scientist, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, and Internist, St. Michael’s Hospital. Dr. Fahad Razak, Scientist, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, and Internist, St. Michael’s Hospital

The challenge: When it comes to treating COVID-19, healthcare data can help us understand what works and what doesn’t. But it’s scattered across Ontario’s hospitals.

The solution: Combine data from more than 30 Ontario hospitals that treat 70 per cent of patients in the province. Then use artificial intelligence and machine learning to analyze it. The upside? With all that data, scientists and doctors can improve diagnosis, treatments and health policies.

Laughing gas: A serious way to fight depression

Dr. Karim Ladha, Investigator, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, and Anesthesiologist, St. Michael’s Hospital. Dr. Sid Kennedy, Scientist, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, and Psychiatrist, St. Michael’s Hospital.

The challenge: While there are many medications that treat major depression – a devastating disorder that affects millions of Canadians – they don’t work in nearly one-third of patients.

The solution: Study whether nitrous oxide, or “laughing gas,” will work in patients with depression based on data that shows anesthetic drugs and gases have antidepressant effects.

The comments section is closed.