The COVID-19 pandemic and its fatal consequences for vulnerable older adults are forcing us to re-examine how communities should respond to those with functional disabilities.

As of May 17, residents of Ontario’s 626 long-term care homes had accounted for a significant portion of all COVID-19 deaths in the province (3,778 of 8,489). Another 603 deaths have occurred in Ontario’s private retirement homes.

When the Canada Health Act was the essence of the health-care system about 60 years ago, older adults comprised 8 per cent of the population. In 2021, older adults comprise 18 per cent and in 2041, this will increase to 25 per cent. Although Ontario has 56,500 older adults living in private retirement homes and 78,000 living in publicly funded long-term care homes, the other 94 per cent of the 2.5 million people in Ontario 65 years and older live in other types of accommodation. Few of us favour moving to care homes, preferring to remain in our own home. Aging in place, staying in one’s home while getting older, is a worthy consideration that provides numerous benefits, including honouring dignity and independence, reducing the risk of illness, faster recovery, enjoying companionship with loved ones and promoting healthy aging.

But while placing hospitals at the centre of the Canadian care system was justified in the last century, the human tragedy of long-term care in Ontario is evidence that it is less appropriate in today’s context of an aging population with complex and long-term conditions and disabilities.

A Canadian Medical Association Journal article outlines the reasons British Columbia’s response to the pandemic in long-term care homes was superior to both the Ontario and Quebec systems: better coordination between long-term care, public health and hospitals; greater funding of long-term care; more care hours for residents; fewer shared rooms; more non-profit facility ownership; and more comprehensive inspections.

Pat Armstrong and her colleagues’ 2019 book Privatization in Six Countries: The Case of Nursing Homes documents how privatization of long-term care homes moves systems “… not only from public delivery and public payment for health services but also from a commitment to shared responsibility, democratic decision-making and the idea that the public sector operates according to a logic of service to all.”

Another consequence of care homes being in the shadow of hospitals is that leadership in these homes often has higher turnover and lower pay than in comparable hospital positions. One necessary corrective action is to improve leadership competency and performance through mandatory enrolment in the Canadian College of Health Leaders program or the HealthcareCan course on Long-Term Care Administration.

The growing number of older adults living with complex and long-term conditions requires a new approach in the distribution of finite health resources: That is, what proportion of our tax dollars should be allocated to care homes? And this political and policy debate needs to cover not only redistributing government funding to account for peoples’ increasing longevity but also health promotion and diversified housing options for older adults.

Policies also should expand the meaning of “community-based” response to include local involvement in health promotion. Many of the underlying health conditions that increase the risk of COVID-19 are closely related to inactivity and diet. Although this can be disheartening because the modern environment greatly contributes to many health risks, it also means that a few, simple lifestyle changes can decrease the risks. When we reach this point in our life, we need safe, relationship-centred support promoting physical and brain health, wherever we live.

We cannot separate the health and social aspects of living as frail older adults. When we are frail, we have a spectrum health events (from acute episodes to more complex, chronic conditions) and we require a spectrum of approaches (from single interventions to long-term, health-promotion interventions) where distinctions between health and social aspects of life are largely meaningless.

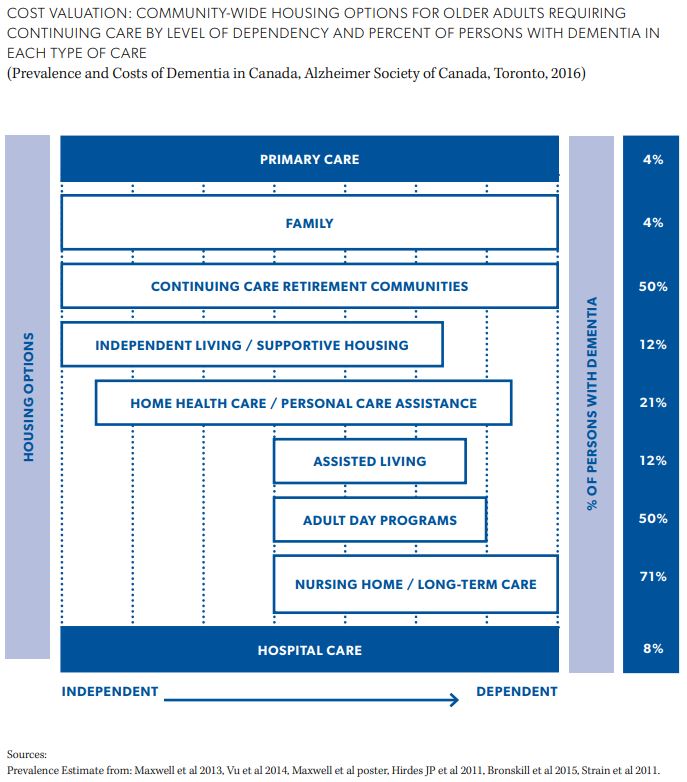

The Housing Options for Frail Older Adults chart outlines several types of community housing, including types for people who are frail. The scale at the bottom extends from independent older adults to dependent older adults. The length of “housing” bars indicate what level of dependency along this scale is supported by each housing option. For example, at-home living with family support is a housing option that supports older adults regardless of where they are on the scale. Note the wide variety of housing options, with availability being a question in each of our communities.

A response to our aging population that exclusively focuses on the number of care-home beds is inappropriate. In addition to high capital and operational costs of care homes, long waiting lists were present even before COVID-19 downsizing to eliminate shared rooms and washrooms. Policies should be based on the principle that every person should have the right to choose where to live.

Few older adults favour moving to care homes, preferring to remain in their own homes and communities or into housing options that enable them to access all community amenities and delay their dependence on care services.

Instead of deferring to the same top-line government officials, what we need is a move to a long-term, community-based and health promotion approach. Consult with community organizations to understand the local challenges in health promotion and housing. Leverage the trust they have built over decades to gain public buy-in. For example, strong and impressive campaigns have been led by mothers on topics such an influenza and safe sleep. And leverage the enormous trust Canadians have for their family physicians.

The tragedy of COVID-19 deaths in long-term care homes in Ontario should be an important catalyst in sparking the conversation within our communities about how they should adapt in response to changing demographics. A paradigm shift to Canada’s approach to promoting the health of our aging population is long overdue. The cost of institutional accommodation and care – to residents, their families and governments – outstrips the cost to provide for older adult needs through broadened health promotion and housing policies and innovations.

The comments section is closed.