We’ve all seen the headlines linking COVID-19 vaccines to rare blood clots. While developments like Ontario’s decision to pause AstraZeneca vaccines may be worrisome, they are reassuring signs that vaccine safety surveillance is doing its job.

“We’re trying to roll out a vaccine program to 7 billion people around the world,” says Karina Top, an associate professor at Dalhousie University who studies vaccine safety. “There is always potential for very, very rare adverse events that occur in less than one in 10,000 or one in 100,000 people.”

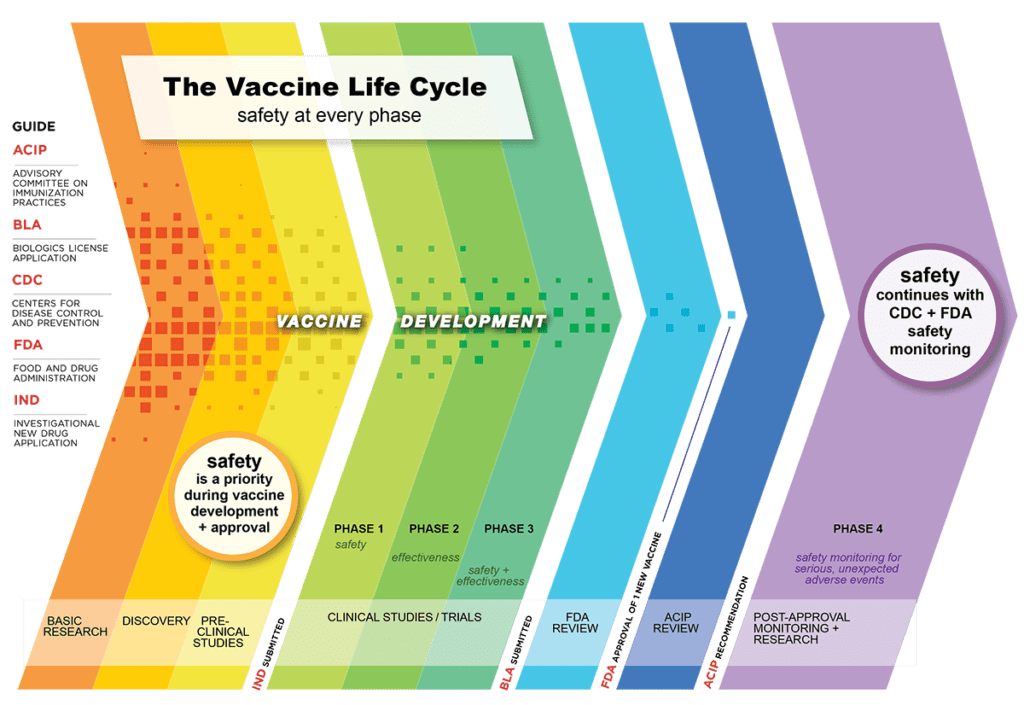

Vaccine safety is monitored at all stages of clinical trials but the trials themselves are not designed to detect such rare events. Nor can they assess safety in groups who are deliberately excluded, like those with compromised immune systems or pregnant women.

For these reasons, surveillance continues long after a vaccine has been rolled out, in the form of what epidemiologists call Phase 4 or post-marketing studies.

“The continuous monitoring of safety doesn’t end with a Phase 3 clinical trial,” says Maria Sundaram, a postdoctoral fellow with the Centre for Vaccine Preventable Diseases at the University of Toronto. “We continue to do safety monitoring after these vaccines are in use in people. That’s always been the case, but it’s especially the case now for COVID-19 vaccines.”

Passive vs. active surveillance

Post-marketing surveillance falls into two broad categories: passive and active.

In passive surveillance, doctors and other health-care providers report adverse events following immunization, abbreviated to AEFIs (pronounced AY-fees), to local public health units. These reports are submitted to provincial/territorial and federal public health agencies. In Canada, this system is known as the Canadian Adverse Events Following Immunization Surveillance System (CAEFISS).

While passive surveillance casts a wide net across the entire population, active surveillance proactively looks for adverse reactions among a select group of vaccine recipients or solicits this information from their health-care providers. One example is the Canadian National Vaccine Safety (CANVAS) network that is currently enrolling Canadians and asking them to self-monitor their health using an online survey.

Both passive and active surveillance are designed to serve as early warning systems. And it’s thanks to these surveillance networks that public health authorities have picked up the rare cases of serious blood clots associated with the AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson (J&J) vaccines.

Whenever a safety signal appears, epidemiologists and other public health experts try to figure out how common the event occurs in the general population and whether it is occurring more often among vaccine recipients.

“The first question to ask is: ‘Is this real?’” says Top. “How many reports of a certain adverse event would you expect in a given time period, and then how many did you receive?”

Whether these events occur soon after vaccination, or temporality, is just one piece of evidence that epidemiologists use to establish if the vaccine is the cause. They also must consider whether there is a plausible biological explanation, whether the event is seen consistently in different populations, and the strength of the association, among other factors.

Once a causal link is found, health-care providers are alerted to be on the lookout for more cases to ensure they are appropriately recognized, diagnosed and treated. That communication is one reason why the U.S. recently paused its roll out of the J&J vaccine. It also requires updating vaccination guidelines.

“It’s a good example of the system working as it should,” says Top. “When we are talking about risks that occur in one in 100,000 or one per million, that’s a level where the benefit of vaccination is still going to outweigh that small risk.”

Public health decision-making

The National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) updated its guidelines in early May to preferentially recommend the mRNA vaccines produced by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna over the viral vector-based ones from AstraZeneca and J&J. But it also said the J&J vaccine could be offered to adults aged 30 and older if the benefits outweigh the risks, following a similar decision in April for the AstraZeneca product.

Some have suggested that NACI’s statement may encourage vaccine hesitancy while others think the situation is much more nuanced and complex. Sabina Vohra-Miller, a health advocate and co-founder of the Vohra Miller Foundation, views these evolving guidelines as reassurance that public health authorities are adapting to new information as it becomes available.

“Policy is always playing catch-up to science,” says Vohra-Miller. “The issue with COVID-19 is that the science is evolving so fast that policies are having a hard time catching up.”

Doctors had identified 10 cases, including three deaths, of blood clots – called vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT) – across Canada as of early May. That’s out of more than 2 million people who had received at least one dose of the AstraZeneca vaccine.

NACI estimates that between one in every 100,000-250,000 vaccinated people will develop VITT. However, it could be as common as one in every 26,000, according to new guidelines from Ontario’s COVID-19 Science Advisory Table.

While vaccine-induced blood clots are treatable, they are more aggressive and more fatal than normal clots. They are also unusual in that they come with a condition known as thrombocytopenia, or low platelets, which help blood clot.

“As a blood clot doctor, these are scary blood clots,” says Menaka Pai, an associate professor of hematology at McMaster University. “Patients can do well with early detection and treatment. But these are serious clots. And sometimes the outcomes are very poor, despite really good treatment.”

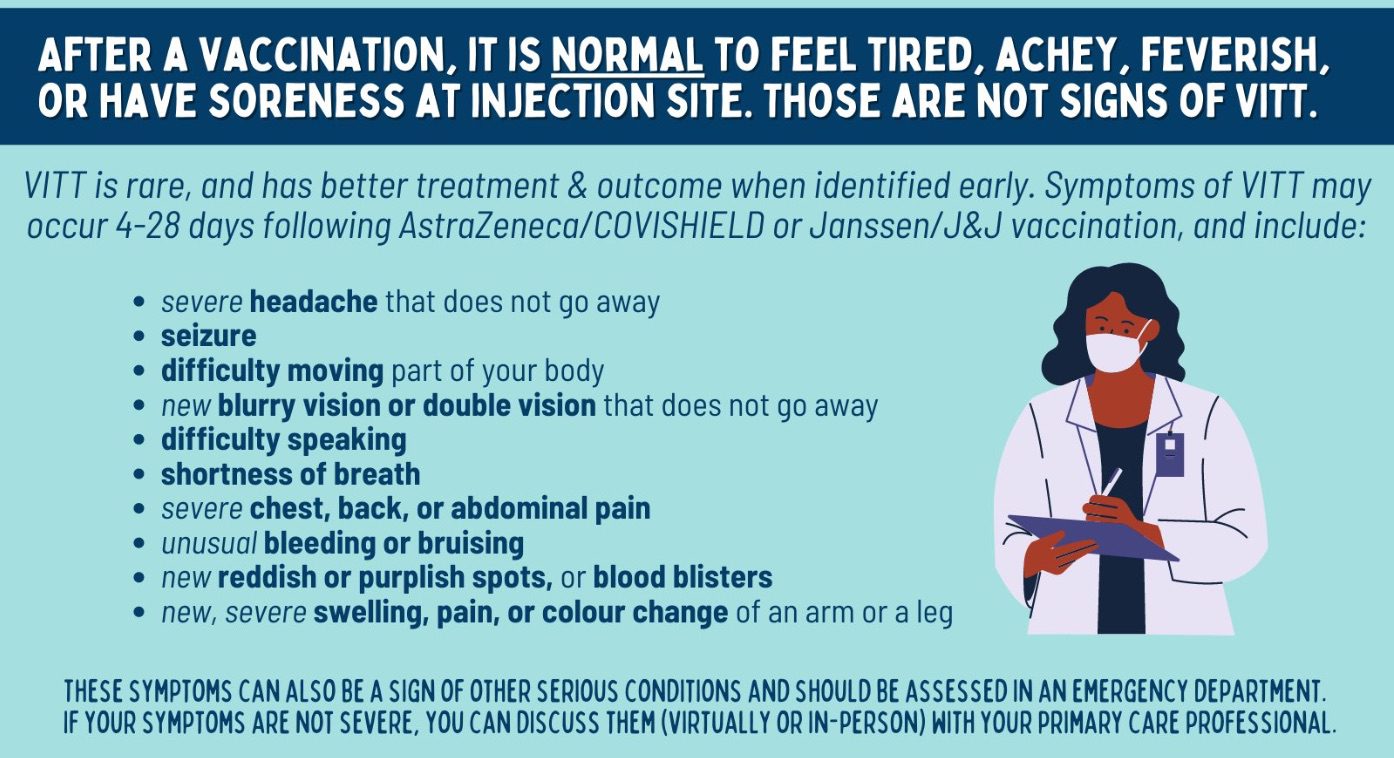

Experts advise vaccine recipients to become familiar with the symptoms of blood clots and to contact a doctor or hospital immediately if they develop symptoms. These include shortness of breath, chest or abdominal pain, swelling in the legs, severe headaches or blurred vision, and skin bruising or a rash. Most occur within four days to two weeks after immunization but can take up to 28 days.

Source: via Twitter @heysciencesam (https://twitter.com/heysciencesam)

“Especially with VITT clots, coming in early to the hospital and seeking medical attention in a timely fashion is critical,” says Pai. “If we can intervene early, we are increasing the odds that you will survive.”

According to NACI, between 25-40 per cent of VITT cases can be fatal. But it’s important to put the risk in context, say experts. The chance of dying from a vaccine-induced clot depends on what statisticians call a “conditional probability.” In other words, the risk of death depends on the extremely low risk of developing a blood clot in the first place. Similarly, the likelihood of being admitted to an ICU due to COVID-19 – or developing a blood clot from COVID-19 itself rather than the vaccine – depends on first being infected with COVID-19.

“I believe NACI made a recommendation based on the science,” says Pai. She suggests that people considering the AstraZeneca or J&J vaccines should be empowered to make an informed decision about their individual risks. How the latest NACI guidelines will affect public confidence is an open question, however.

Risk communication

Because vaccines are given to healthy people, public health officials and the public typically have a low tolerance for risks. Health Canada conducts its safety reviews based on clinical trial data from manufacturers for specific vaccine products before granting authorization. It continues that review once a vaccine is on the market.

NACI then assesses those risks in the context of the vaccine program as a whole – including whether other products, like mRNA vaccines, are available – by synthesizing evidence from various sources. These policies must apply to the entire population, even though vaccine decisions are often made at the individual level. It currently recommends that individuals should consider their particular circumstances when choosing a vaccine product.

One of those variables involves weighing the risk of blood clots against the risk of succumbing to COVID-19 if unvaccinated, which could depend on a person’s age and exposure risk as well as community transmission rates, among other factors. For example, the AstraZeneca vaccine initially may have been a no-brainer for an essential worker in a hard-hit region like Peel in Ontario but less urgent for someone in the Atlantic provinces.

While some might view this as ‘risk’ versus ‘no risk,’ Sundaram prefers instead to reframe it as competing risks. “It’s important to remember that we’re balancing this risk and its benefit,” she says. “And the risk of COVID-19 is also changing because the epidemiology is changing.”

Her advice: “The best vaccine is the one that you can get the quickest. It has the most ability to protect you for the longest time. And especially in places where there are high levels of community transmission, we need protection now.”

But she adds this caveat: “The best vaccine is the one that you feel comfortable taking.”

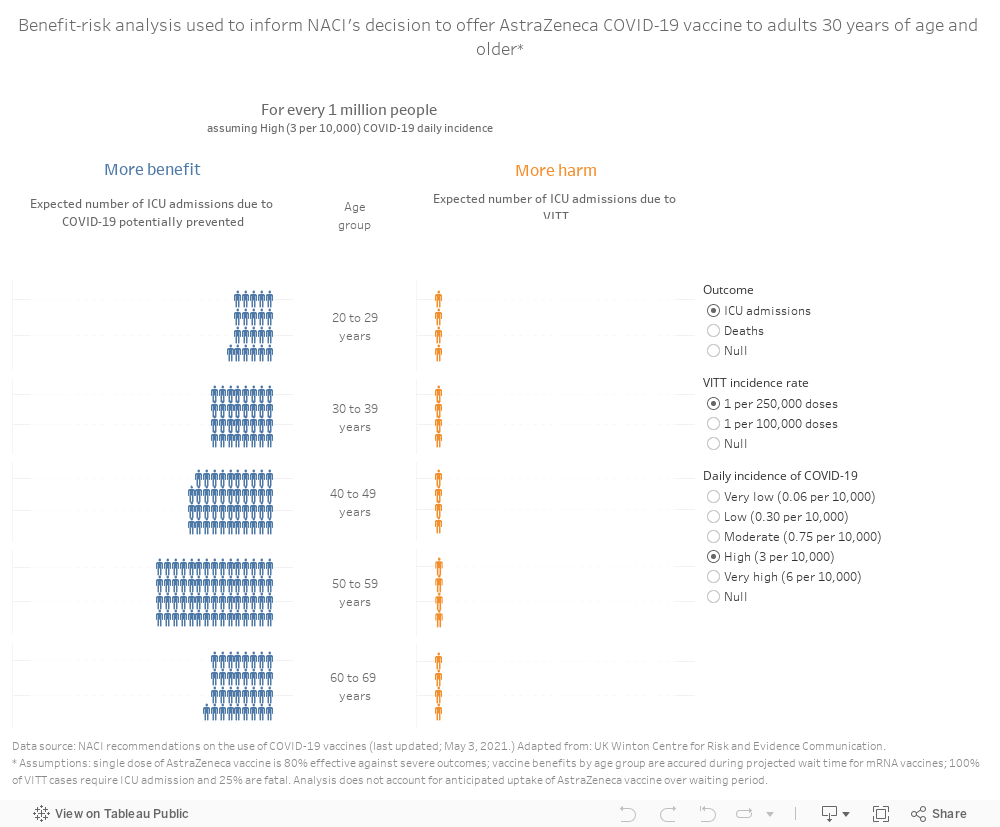

NACI’s recent analysis found that the number of COVID-19 ICU admissions and deaths preventable by the AstraZeneca vaccine while waiting for an mRNA product would be higher than the expected number of VITT cases, even in some scenarios where the COVID-19 exposure risk was low to moderate. The model assumed that the risk of blood clots was the same across all age groups. (Although initial reports suggested that clots may occur more often in women under age 55, this group may also be overrepresented among early vaccine recipients.) It found greater benefit from the vaccine among adults 30 and older who are at higher risk of becoming severely ill with COVID-19.

var divElement = document.getElementById(‘viz1620749969710’); var vizElement = divElement.getElementsByTagName(‘object’)[0]; if ( divElement.offsetWidth > 800 ) { vizElement.style.width=’1000px’;vizElement.style.height=’827px’;} else if ( divElement.offsetWidth > 500 ) { vizElement.style.width=’1000px’;vizElement.style.height=’827px’;} else { vizElement.style.width=’100%’;vizElement.style.height=’2027px’;} var scriptElement = document.createElement(‘script’); scriptElement.src = ‘https://public.tableau.com/javascripts/api/viz_v1.js’; vizElement.parentNode.insertBefore(scriptElement, vizElement);

(Tableau infographic best viewed on desktop or tablet.)

Media headlines often fail to capture the full story behind these statistics. We regularly hear about the one rare adverse event following immunization, but rarely about the success of vaccines in averting hundreds or thousands of COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations.

Experts urge better communication. “It’s been my experience that transparency is helpful in developing trust,” says Sundaram. She and others advocate for public health decision-makers to be more transparent and put the risks of these rare but serious blood clots into the context of other risks people take in their daily lives.

Vohra-Miller agrees: “When you minimize the side effects, you’re chipping away at people’s trust. And once you chip away people’s trust, it takes 10 times more work to build it back up.”

The comments section is closed.