My friend Gaby and I have had drastically different experiences getting access to COVID vaccines in Toronto – mainly because of our postal codes.

My family lives downtown, where we’ve worked and schooled from home throughout the pandemic. We learned from our local health unit that because our building is in a “hot spot” (a part of the city where COVID-19 infection rates are higher than other areas), we were eligible for vaccine appointments. We walked to the local site and were vaccinated within minutes. Gaby lives in a multi-generation household in North York where two members are essential workers. Despite being at significantly higher risk, she did not receive email from her local health network and instead had to search for vaccines for her family using a tool she found on social media: Vaccine Hunters Canada.

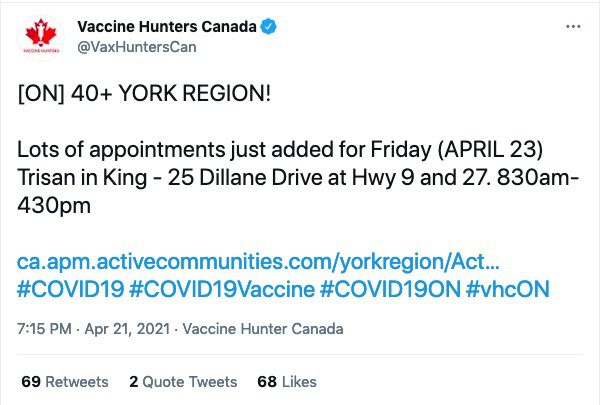

Vaccine Hunters is a volunteer-based, grassroots, online tool that helps reduce vaccine waste while promoting health equity, which has been sorely lacking in Ontario’s vaccine rollout. (More on that below). Its creators use social media to get the word out about extra vaccines and appointments that could otherwise be wasted. The Vaccine Hunters team reviews and shares pharmacy, clinic and public health unit updates as well as other crowdsourced information on Facebook, Discord and Twitter. For those with access to the internet, it’s easy to use and customizable: for example, Twitter users can type in @vaxhunterscan followed by a space and the first 3 letters of their postal code for up-to-date info.

It is a sad testament to Ontario’s vaccine rollout that high-risk families in Toronto have to scramble with social media tools just to get vaccines. But mixed-income neighbourhoods are not reflected in the vaccine rollout, with the newest approach suffering from a tunnel-vision focus on geographic regions based around epidemiological data (hot spots) more than identifying high-risk individuals based on employment, disability, health status and other factors.

In mid-April, the provincial government committed 25 per cent of future vaccines to 13 regions with the highest rates of COVID deaths, hospital admissions and transmission, boosting a “hyper-local” approach. But what if you’re high risk, like Gaby’s family members, and you don’t live in one of the hot spots? Not to mention the confusing multiplicity of booking systems using different eligibility. Some clinics book appointments online; others require people to line up and get tickets.

Because of these inequities, Vaccine Hunters is serving a dual role: not only working to eliminate vaccine waste through its communication channels but offering opportunities to high-risk individuals who fall into the no-man’s land outside of the hot zones. “It’s our duty as Canadians to help those that are most at-risk and vulnerable,” Vaccine Hunters co-founder Josh Kalpin told the National Post.

Like the rest of Canada, Ontarians in search of vaccines have embraced the Vaccine Hunters tool. For example, on April 22, Humber River Hospital had no line at their Downsview Arena pop-up clinic and opened up vaccinations to any resident of Toronto that was 40 years or older, regardless of postal code. Vaccine Hunters shared the information on social media and within less than three hours, 600 people were standing in line to be vaccinated. Similar scenarios have happened with other pop-up clinics in the region.

Gaby’s brother, who’s in his early 20s and works in a busy restaurant, is unfortunately “among the last to be prioritized,” she says. The siblings joined the Vaccine Hunters Discord server, which is divided into channels based on region and other factors.

“Typically the volunteers keep an eye out for any bookings that get cancelled,” explains Gaby, “and they ask if you want to be pinged the moment something becomes available. The one limitation of course is that you have to be fully prepared to get out the door. The first time, I got offered a slot in ten minutes. They were super understanding that I couldn’t arrive on such short notice. Then one of the volunteers offered to help me register through one of the networks for the next possible slot.”

She describes the moment she was vaccinated: “Relief.”

The pandemic has further revealed stark equity gaps in health care access for racialized people and essential workers. Our provincial government, which canceled paid sick leave for workers in 2017, spent more than a year pushing back against calls to renew it, most recently voting it down on April 26—then, in a surprising turn, approving three days of paid sick leave on April 28. Workers spent more than a year without being able to stay home when sick and many have not been vaccinated, remaining at serious risk.

According to Dr. David Fisman, a Professor of Epidemiology at the University of Toronto, scientific advisors to the Ontario government have seen their “guidance on prioritization perverted, with [priority] linked to the ridings of members of the government prioritized.” Fisman notes that essential workers don’t have the privilege of working remotely, nor job security or benefits. “So what we’ve seen over and over again is people in these situations acquiring COVID in the workplace and bringing it home to multigenerational households.”

From the data–and from the frontlines–it’s clear that the virus disproportionately impacts racialized people. As Toronto physician Seema Marwaha has written: “When you walk through a COVID ward in the GTA…you see who is suffering during the pandemic. Racialized people who are or live with essential workers. People who are working at risk so that our society can still run. It is so incredibly obvious to us on the wards who is struggling for help.”

Gaby, who is Latine, notes that by focusing vaccine efforts geographically, the province is neglecting to protect those at risk who live outside of hot spots and in mixed-income neighbourhoods.

“The message I get is we are ‘not deserving of protection and that we need to just work harder,’” says Gaby, “even though most of us are practically burnt out from complying with health guidelines while privileged groups continue to flout said guidelines and laws. This is also yet another reason why Black folks in particular are loudly and unapologetically declaring Black Lives Matter.”

The story of grassroots initiatives like Vaccine Hunters Canada has brought to light larger issues of health equity in the rollouts—and the need to think outside the box. Last week, the City of Toronto acknowledged that it could leverage the communication tools of Vaccine Hunters and officially began partnering with them. But that’s not all that governments can learn from the Vaccine Hunters experience. As health workers and policymakers race to get as many vaccines into arms as they can, it’s crucial to assess the structural causes of health inequity.

“Vaccination is part of the puzzle,” says Fisman. “We also need safe workplaces and schools, paid sick leave and job security so people aren’t fired for taking time to get vaccinated or to isolate.”

Equity also means promoting leadership in health policy decisions for those most affected by them.

“BIPOC and disabled people must be the ones leading future rollouts,” says Gaby, “because we’re the ones experiencing the greatest ongoing repercussions from the pandemic.”

The comments section is closed.