Understanding the history of health care’s gender segregation, the basis for today’s “pink collar” tier of female-dominated specialties, will aid current efforts to improve pay equity in medicine.

Gender segregation in modern health care arose from the traditional association of care work with “women’s work” in societies that also barred female access to education or paid occupation. A wide range of health-care labour fell under the domain of subordinated female health-care workers. Meanwhile, from ancient times onward, men habitually positioned themselves to lead scientific and professional developments in medicine.

Birth attendants were exclusively female for most of recorded history, but in the 18th century an increasingly professionalized class of male doctor in the West began expanding into the traditional domain of unpaid female practitioners. Advances in asepsis and anesthesia throughout the 19th century improved the safety of hospital birth and caesarean section, bringing obstetrics into the realm of the male surgeon.

The formal encoding of “women’s work” in health care began with the professionalization of nurses, which in Canada occurred in the late 19th century. Built on a foundation of feminine domesticity and voluntary service, nursing developed in concert with contemporary middle-class values of efficiency, order and evangelism. The gender essentialism of Victorian culture was also woven into this newly professionalized role, formalizing the identity of nurses as feminine helpmeets to masculine doctors.

Medical education was barred to Canadian women until the turn of the 20th century.

Medical education was barred to Canadian women until the turn of the 20th century, a victory achieved after decades of activism. Much of the advocacy to end medicine’s gender exclusivity was (perhaps ironically) rooted in Victorian gender ideology, with activists claiming that women’s inherently maternal natures would elevate the profession. This theme ran parallel to contemporaneous feminist arguments that women deserved a role in public life because maternalism could heal social ills.

The association with maternity gave women purchase in certain areas, like maternal and child health. For many nurses and female doctors in the early 20th century, maternalism was a stepping stone to the nascent field of public health, a feminine-coded discipline that was less attractive to men and thus had more opportunities for leadership. Indeed, a number of pioneering children’s sanitation and nutrition programs were developed by women.

After explicit bans against women ended, there followed an era of quotas that restricted female entry until the mid-1960s. The data set in this article originated shortly after medical enrollment fully liberalized, and thus can be taken to represent the entirety of the modern era wherein explicit discrimination is at least frowned upon if not litigated against. The persistence of gender segregation despite large changes to overall gender demographics suggests the continuing influence of historical attitudes toward women’s roles in health care.

What do historical statistics tell us?

The Canadian Institute for Health Informatics publishes historical data on the physician workforce dating back to 1968, which provided the binary gender statistics used in this analysis. A small percentage of physicians were reported as “sex unknown” in the earliest years of data collection: 6 per cent in 1968-69, and then on average 2 per cent between 1970 and 1987. Statistics on non-binary physicians were not collected.

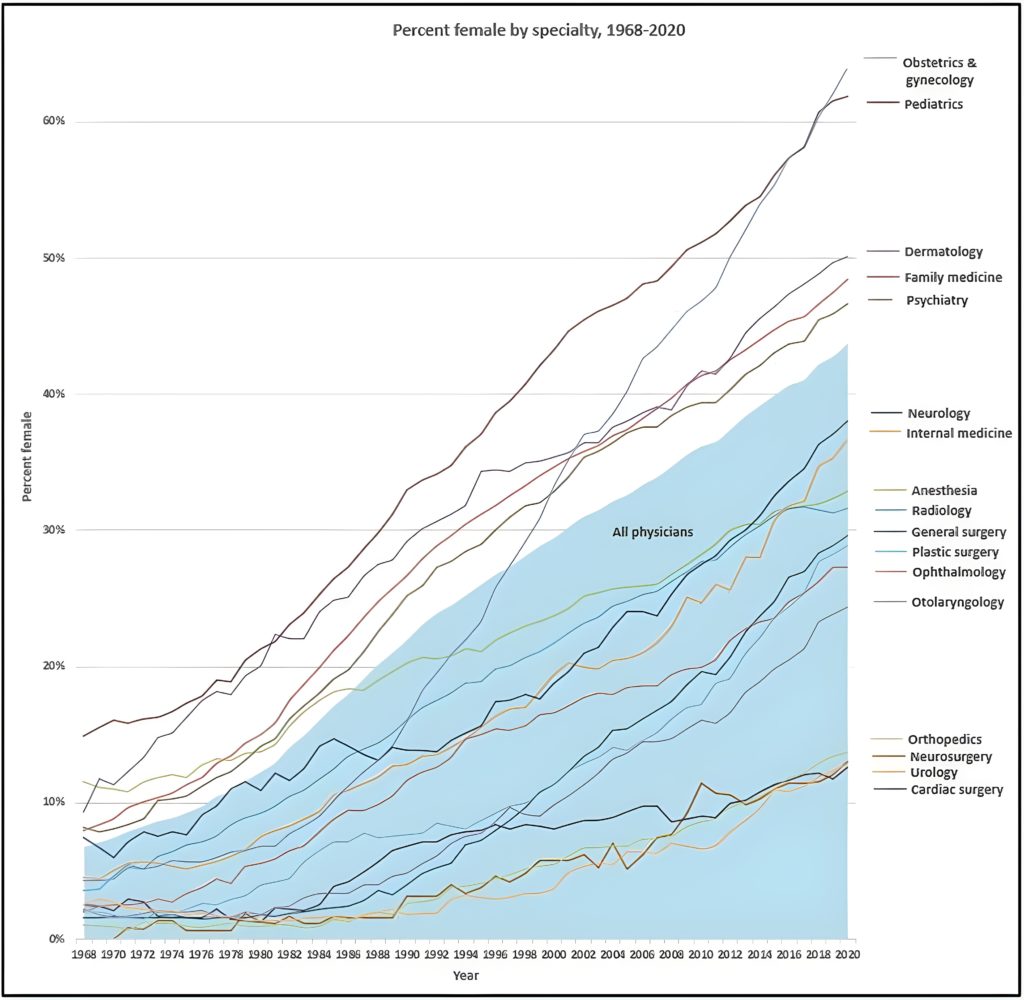

Demographic data show a large shift in overall female representation, from 7 per cent in 1968 to 44 per cent in 2020. Women are concentrated in family medicine/general practice, dermatology, psychiatry and pediatrics as shown in Fig. 1. When compared to the overall growth of women in medicine, those four specialties were consistently above par in female percentage – i.e., above the blue area that represents all physicians.

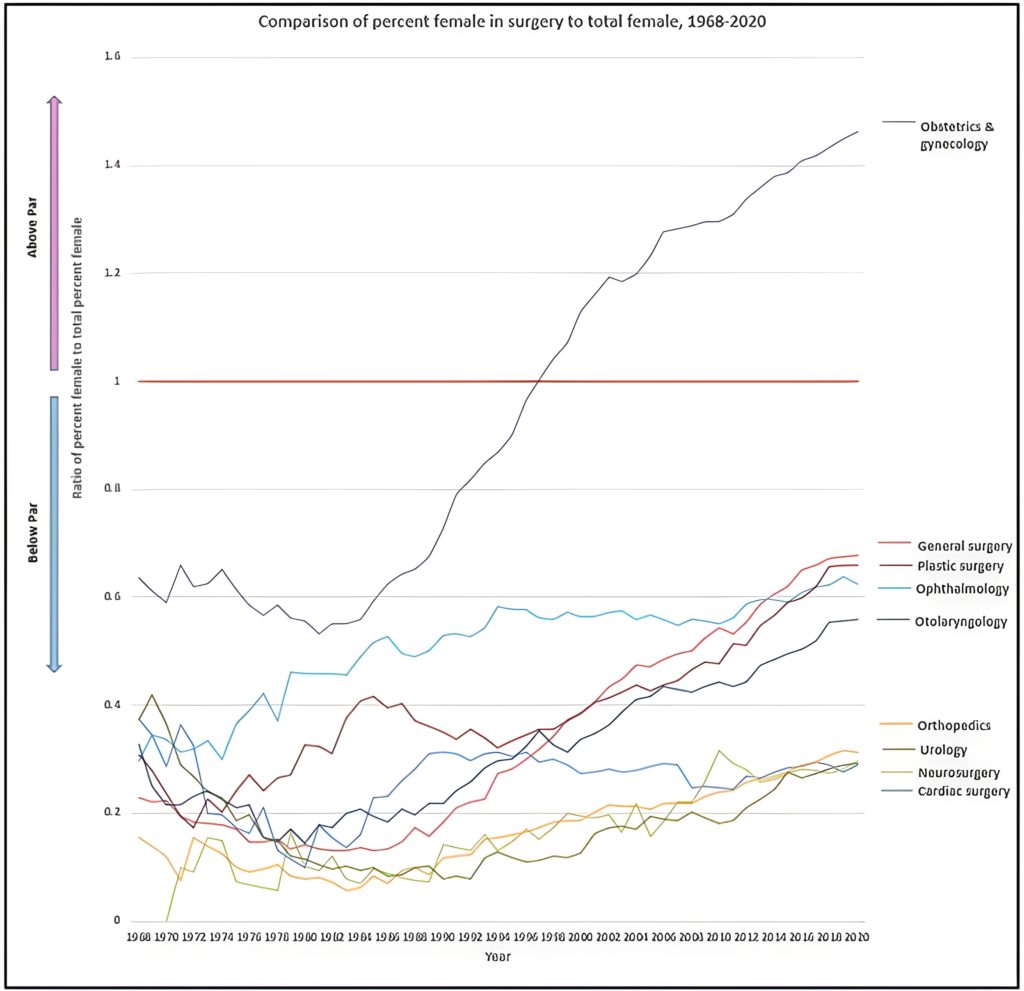

Most specialties changed little in terms of relative female representation, with the singular exception of obstetrics and gynecology, which made a dramatic demographic shift in the mid-1980s. In 1997, the specialty reached parity with the overall number of women in medicine; in 2018, it became the specialty with the highest concentration of women.

By contrast, the scant female entry into other surgical specialties is striking, especially when compared to the overall growth of women (Fig. 2). The majority of surgery remains well below par throughout, particularly orthopedics, urology and neurosurgery.

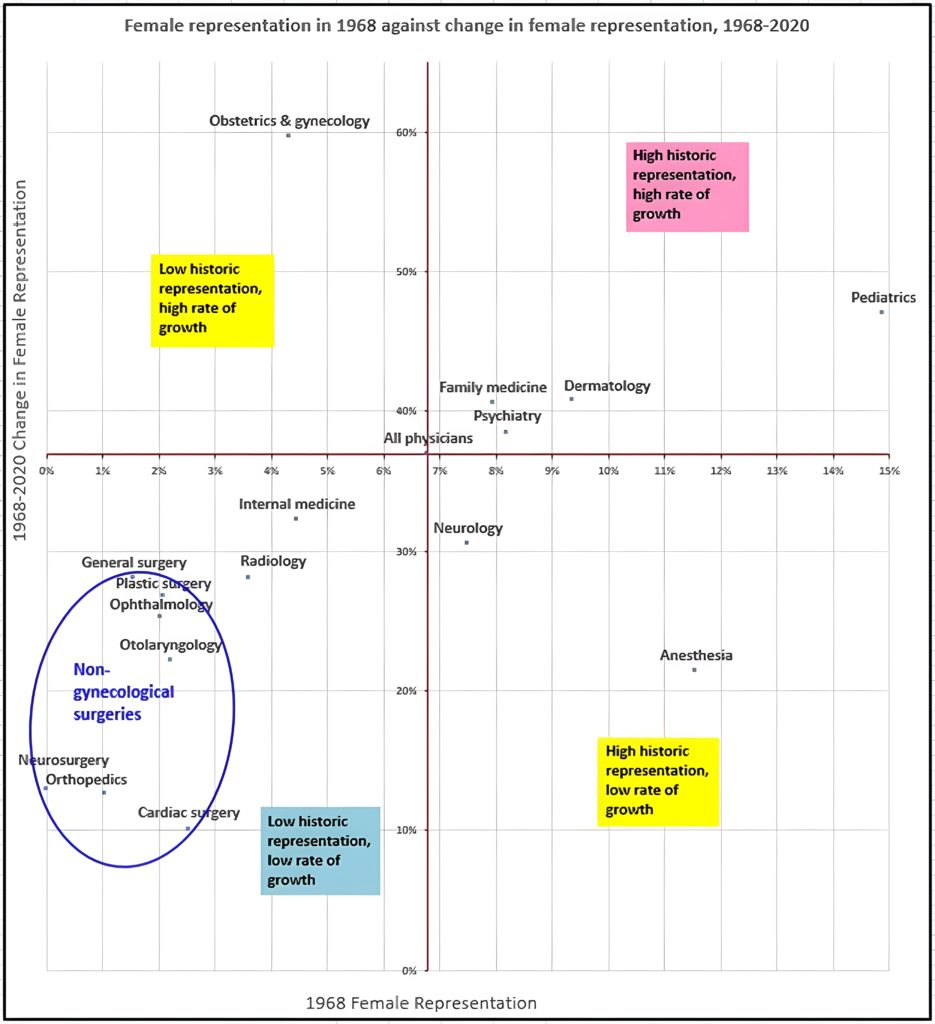

A scatterplot comparing historical female representation to the growth in female representation shows obstetrics and gynecology to be distinct from the other surgical specialties, which cluster together in the quadrant with least female entry (Fig. 3).

These statistics demonstrate the existence of a gender segregated “pink collar” tier in Canadian medicine. After being restricted to informal and subordinate roles in health care, women carved out professional space in areas they had claim to by virtue of their femininity. When the medical education system liberalized and women matriculated in ever greater numbers, they continued to move disproportionately into specialities traditionally associated with feminine traits.

Slow female entry into nearly all surgical specialties can also be well understood within this context, as many masculinized traits like power and control are associated with surgery. It’s unclear to what degree the uneven distribution of women is a result of sexist discrimination as opposed to freely made choices, however, the profession’s long history of male gatekeeping and female exclusion suggests the persistent influence of gender bias in health-care work.

The data show a flood of female entry into obstetrics and gynecology beginning in the mid-1980s, more than 70 years after Jennie Smilie, Canada’s first formally licenced female surgeon, removed an ovarian tumour on a kitchen table because no hospital would employ her. Some 50 years earlier, reformers had argued that the health of female patients suffered without female physicians. Viewed in this light, obstetrics and gynecology’s demographic shift in the late 20th century could be seen as the culmination of more than a century of activism for representation in women’s health care.

Canada’s first formally licenced female surgeon removed an ovarian tumour on a kitchen table because no hospital would employ her.

Female entry into the field of surgery has been highly segregated. That women can become the dominant gender in a surgical specialty indicates that no inherently masculine skills are needed to be a successful surgeon. Further study and discussion within the surgical community is warranted, as gender segregated niches within an industry can perpetuate historical marginalization despite improvements to representation overall.

Understanding this history can aid current efforts to improve pay equity in medicine – often called “relativity” to refer to a framework for fairly evaluating different types of medical work. Relativity analyses typically lack discussion on gender. However, there is a positive relationship between female dominance and low relative income in the medical specialties, suggesting that work associated with stereotypically feminized skills is remuneratively undervalued.

It is essential to appreciate the biases against female-coded labour and how those biases are informed by a history of restricting women’s occupation. Pay equity in the profession will necessarily include a comprehensive grasp on historical discrimination and its lingering influence on gender segregation in the specialties.

The comments section is closed.