For International Overdose Awareness Day (Aug. 31), Healthy Debate sat down with Dr. Susan Boyd to discuss her latest book, Heroin: An Illustrated History.

Boyd is a scholar, activist and Distinguished Professor emerita at the University of Victoria. Her research examines a variety of topics related to drug prohibition.

In Heroin, Boyd points to our failure to address the overdose death epidemic and the decades of resistance to harm-reduction policies. The book looks at two centuries of Canadian heroin regulation and explores themes such as systemic racism’s contribution to prohibition and the structural violence of drug policies that use criminalization as the main response to drug use.

Boyd works with groups that provide harm-reduction services and organizations working to end drug prohibition, such as the Canadian Drug Policy Coalition. She teaches several courses including research methodologies; social and cultural perspectives on drug issues; media representations of drug issues; women and drugs; and critical theory.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

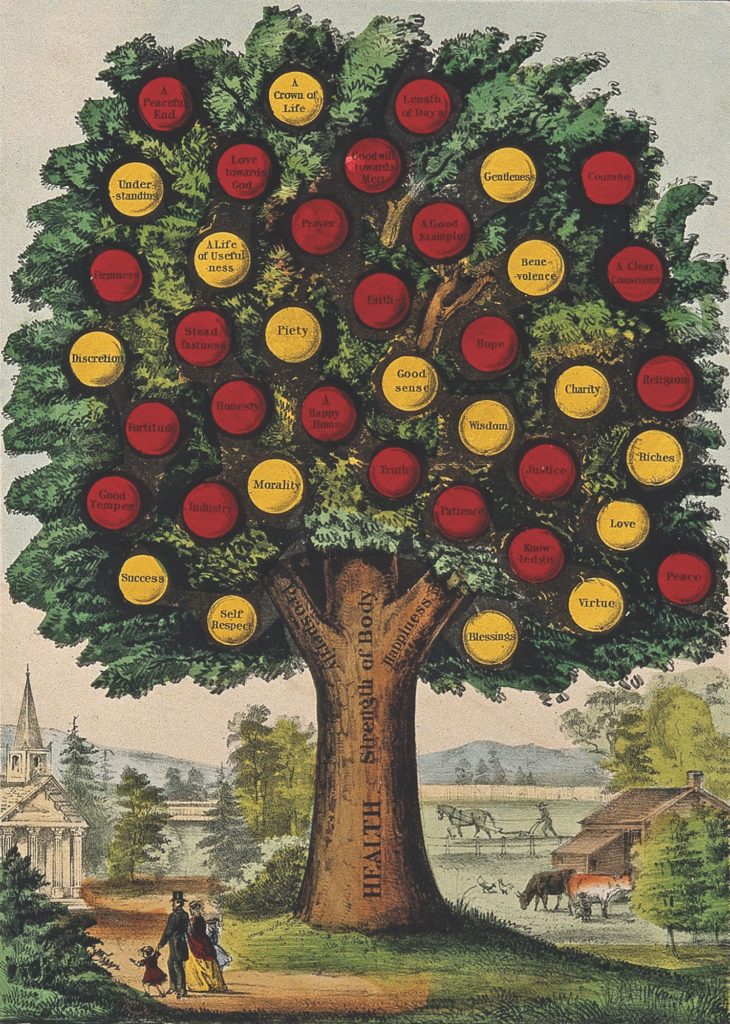

In both Busted: An Illustrated History of Drug Prohibition in Canada and Heroin: An Illustrated History, you’ve used archival photographs and illustrations throughout the book. It’s visually stunning. Why did you choose to incorporate such strong visual components in both books?

We are saturated by images every day. Similar to text, images tell a story. I wished to tell an alternative history via text and images.

For over a century, lurid representations of alleged “junkies and addicts” have been produced and disseminated by law enforcement, politicians, medical professionals and others through film, print and other media, language, theory and texts, producing a constellation of myths and stereotypes that contribute to legal and social discrimination and stigma.

Stereotypes reduce people to a few essentialist characteristics, accomplished partially through representation. Stereotyping occurs most often when there are “gross inequalities of power,” so that some meanings of an image are privileged over others. Images accumulate meanings over time and play off one another, but often one image is repeated over and over again in texts and visual representations (in print, television and online news, police reports and popular media and films). Think of the negative images and stereotypes you have been exposed to over time about people who use illegal heroin. Most often they are poor and racialized people, and equally often include the iconic image of “shooting up.” This image is now associated with deviance and degradation.

I wanted to tell an alternative history about heroin, criminalization, and the people who use heroin. Neither to demonize or sensationalize or romanticize the drug or the person using it. Each image represents a particular historical event in the regulation of heroin and resistance to that regulation.

Lastly, a reader may not be interested in the regulation of heroin but might find the images compelling. The images might entice the reader to continue reading.

In Busted, you covered the history of drug policy and resistance to prohibition in Canada. Why did you decide to focus on heroin for this book?

Busted examined the history of Canadian drug prohibition more broadly. For example, in Busted, a whole chapter is devoted to cannabis regulation. Another is about alcohol and tobacco regulation.

In Heroin, I highlight the regulation of heroin, as it became the template for further criminalization and ideas about “addiction” and people who use illegal drugs. In Heroin, I challenge ideas about criminalization, punishment, addiction and treatment.

Canada is experiencing the worst illegal drug overdose death epidemic in its history. Between 2016 and 2022, more than 26,000 people in Canada have died from entirely preventable overdoses of illegal drugs.

These deaths are due to prohibitionist drug policies and practices, a poisoned illegal drug supply and inadequate access to flexible and culturally appropriate drug-substitution programs.

The question that looms large is why all levels of government failed to act to prevent these deaths early on. Are these lives not worthy? Why weren’t legal, safe heroin and other substitution drugs provided across Canada to save lives? In trying to answer these questions, I also explored more fully resistance to our deadly drug policies by activists, drug-user unions, harm-reduction activists and allies.

I also hoped to demonstrate that drug prohibition is tied up with colonization and systemic racism, as well class and gender injustice, both in Canada and globally. Since their inception, our drug laws and policies continue to fuel systemic race, class and gender injustice. In fact, they are premised on the framework in the Indian Act, which enshrined ideas about “medical and non-medical” use of drugs, federal criminal sanctions and punishment to curtail drug use.

Rather than adopting a health and social approach – an approach that would allow for personal possession and focus more on education, based on civil fines and less punitive sanctions for illegally selling small amounts (similar to tobacco regulation) – drug prohibition in Canada started out with and still primarily uses a criminal justice approach that contributes to race, class and gender injustice.

In Heroin, you highlight this concept of the “criminal addict” in Canada’s drug policy history. Can you share a bit about what the “criminal addict” framework is and why it’s important in understanding how drug policy and public attitudes would form over the course of the 20th century? How do we still see this construct show up today?

Prior to the 1900s, people who used heroin were not seen as criminal or pathological. Rather, people were able to buy the drug legally with or without a prescription. The transition from law-abiding citizen to “junkie” or “criminal addict” is a product of drug prohibition. For over a century, heroin has been portrayed as highly addictive and destructive. In Canada, people who used heroin would also be labelled as “criminal addicts” to emphasize their supposed criminal nature.

Publicly funded drug treatment had one goal: abstinence. Abstinence-only treatment fails many people.

In Canada, unlike western nations like the U.K., the concept of the “criminal addict” was advanced in the 1930s to explain the nature of illegal drug use and to justify punitive laws. People labelled criminal addicts were seen as criminals first and foremost, and their drug use was considered secondary. Thus, it was believed that even if poor and working-class people stopped using heroin or other illegal drugs, they would remain a menace to society due to their criminal nature. Stemming from these misinformed ideas, publicly funded drug treatment was not set up in Canada until the late 1950s and reformers striving to establish heroin clinics were rejected by law enforcement, moral reformers and law-and-order politicians.

Also, publicly funded drug treatment had one goal: abstinence. Abstinence-only treatment fails many people. It was not until the 1990s that harm-reduction services emerged in Canada; yet they are terribly underfunded and can’t reasonably curtail all the harms stemming directly from drug prohibition.

One of the themes that runs throughout Heroin is of the many inequalities surrounding drug-use prohibition. You provide numerous examples where our laws are applied unevenly over different periods of time. Are there any particular examples that are the most salient today? Any that you feel might be particularly surprising for readers?

Canadian scholars Akwasi Owusu-Bempah and Alex Luscombe noted in 2021 that there is “little information on racial disparities in drug arrests” in a Canadian context. This is due to the fact that Statistics Canada did not request information on race from police services.

Recently, to fill this gap, researchers and news reporters have submitted freedom of information requests to specific police services for rates of arrests by race for drug and other offences.

Reports pointing to the over-policing of Indigenous and Black people in Canada also note that racial injustice is systemic. Like Indigenous peoples, drug-use surveys demonstrate that Black people use criminalized drugs at the same rate as white people. Yet, arrest data from five major cities (Vancouver, Calgary, Regina, Ottawa and Halifax) in 2015 also found that Black and Indigenous peoples were racially profiled by law enforcement and grossly overrepresented in cannabis possession arrests. In Vancouver, the arrest rate for cannabis possession was 21.5 per 100,000 people for Indigenous men, 23.3 for Black men and 5.5 for white men. Calgary, Halifax, Ottawa and Regina also showed similar racial differences for cannabis possession arrests.

In Toronto, Black people make up about eight per cent of the population. Yet, Black people made up 28 per cent of Toronto’s non-cannabis drug possession offences, even though their drug use rates were lower than other racial groups.

The criminalization of heroin, and other drugs, and resulting encounters with law enforcement and other institutions have an effect. Indigenous and racialized people in Canada are not more criminal than white people; rather, they are criminalized.

The medical system has had a long, complex history with drug distribution and dealing with the legal system, which you detail in your book. Over the past few years, there’s been a lot of discussion around the role physicians should play in prescribing “safer supply.” What do you see as the role that physicians have to play in supporting more equitable and humane drug policies?

In the 21st century, despite the advent of harm reduction in the 1990s, people labelled addicted or dependent on illegal heroin and other opioids continue to be seen as deviant, criminal and/or pathological. Researchers assert that repeated and regular drug use does not need to be understood as a fixed pathological identity or a “neurobiological condition.” Instead, addiction could be understood as a habit rather than a pathology.

Conventional theories about addiction and drug policies ignore how the experiences and outcomes of drug use are influenced by one’s race, class, gender or sexuality and one’s cultural, legal and social environment. Nor do conventional theories take into account people’s expectations of a drug, or the context of drug use.

Education is key to changing how we understand heroin (and other drugs) and the people who use them.

In Heroin, you give a number of examples of how both film and news media contributed to certain ideas about drug use – particularly criminality. Why did you decide to focus on news media and film throughout the book?

Every day, newspapers, radio and websites communicate the opinions of key claims makers. News reports help shape and circulate ideas and “solutions” about social issues such as heroin and other drugs.

As noted earlier, for over a century, lurid representations of alleged “junkies and addicts” have been produced and disseminated by law enforcement, politicians, medical professionals and others through media producing a constellation of myths and stereotypes that contribute to legal and social discrimination and stigma.

I wanted to provide conventional and alternative media accounts in Heroin. Media representations are one medium, among many, that shape drug policy.

The moral, legal citizen in Canada is seen as white, Christian and sober.

In light of the legalization of cannabis in 2018, Canadians have this perception that we are a fairly progressive country when it comes to drug policy. But as your book demonstrates, this characterization isn’t exactly tidy. Historically, do you think we can characterize our drug laws as “progressive?”

Canada’s drug policies are not necessarily progressive. Early on, Canada was a leader in initiating repressive drug policies. Since the 1990s, we have attempted to adopt some harm-reduction services. It is quite political and there continues to be a lot of resistance to services that are not abstinence based. The moral, legal citizen in Canada is seen as white, Christian and sober.

I wish I could predict where we are heading. There is tremendous effort for change, both domestically and internationally.

Finally, who is this book for? What do you ultimately hope your readers will take away from this book?

Heroin is for lay readers, from teenagers to seniors, politicians, health providers, criminal justice and child protection workers, and scholars. After reading Heroin and learning about activists and drug-user unions and their allies resisting deadly drug policies and setting up life-saving services (even in the face of arrest), I hope readers will understand that change is possible when people come together. I also hope readers will conclude that it is time for a change in drug policies, right now!

All images provided by Fernwood Publishing.

The comments section is closed.