Despite some improvements, reports published in recent years suggest primary care in Quebec performs poorly compared to other Canadian provinces in terms of accessibility and coordination.

Quebec’s primary-care system is mainly based on the Family Medicine Group (FMG) model, in which patients are registered with a family physician who works with a team of other health-care professionals, such as nurses, social workers and pharmacists. FMGs were introduced in 2002 in response to challenges faced by the community-based CLSC model, including a lack of integration with the broader health-care system and difficulties in attracting and retaining family physicians. Today, 65 per cent of the population is registered with a family physician working in an FMG.

Twenty years later, primary care in Quebec has not caught up with the rest of Canada. The OurCare survey conducted last year that garnered more than 9,000 responses from across Canada, with more than 2,500 coming from Quebec, provides some answers.

In Canada, close to one out of five adults (22 per cent) report not having a family doctor or nurse practitioner they can see regularly. In Quebec, the situation is worse – one in three (31 per cent) report not having a family physician or nurse practitioner. Although this proportion is slightly higher than reported by the Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux in April 2023, the fact remains that for more than 2 million Quebecers, the front door to the health-care system is closed. They have no reliable place to turn when they have new, worrisome problems but also no one to help manage chronic conditions, ensure they receive preventive care or coordinate their journey through the complex health system.

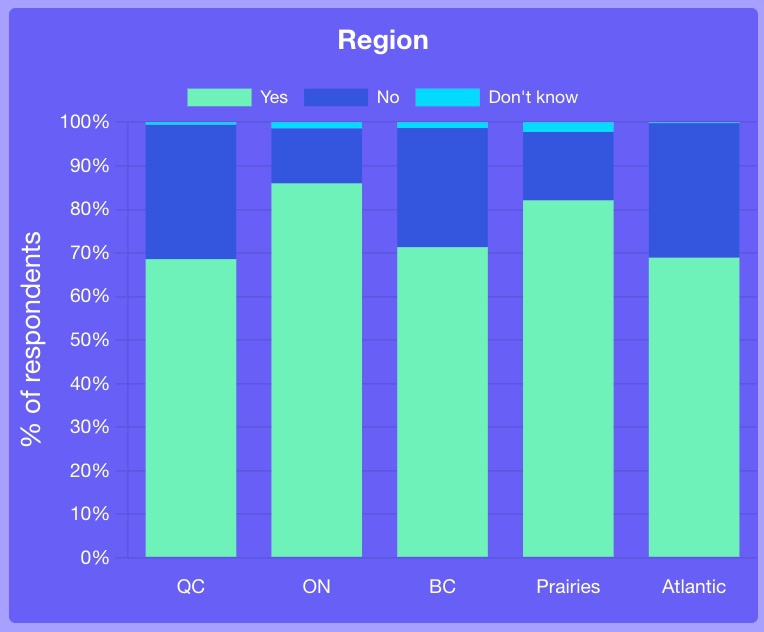

OurCare survey Question 1: Do you currently have a family doctor or nurse practitioner that you can talk to when you need care or advice about your health?

OurCare survey Question 1: Do you currently have a family doctor or nurse practitioner that you can talk to when you need care or advice about your health?

This is despite those earlier investments in interprofessional team-based care, which is often touted as a solution to the problem of accessing primary care. Indeed, the OurCare survey found that compared to other regions in Canada, more Quebecers have a family physician who works with a nurse practitioner, nurse or social worker. But, the context in Quebec is unique with many family doctors required to work elsewhere in the system, contributing to a shortage of human resources in primary care. Furthermore, the fee-for-service payment model does not encourage delegation to other professionals and can result in an unnecessary demand for care.

Despite its reputation as a bastion of social programs, Quebec has faced criticism for gradually opening the door to health-care fees over the past two decades. Of those without a primary-care provider, 37 per cent of Quebec respondents have had to pay a fee for non-urgent care compared to 21 per cent across Canada. The vast majority of those fees were for the appointment itself, suggesting that some people have to turn to the private sector to get the care they need. Such financial barriers disproportionately affect low-income and vulnerable Quebecers.

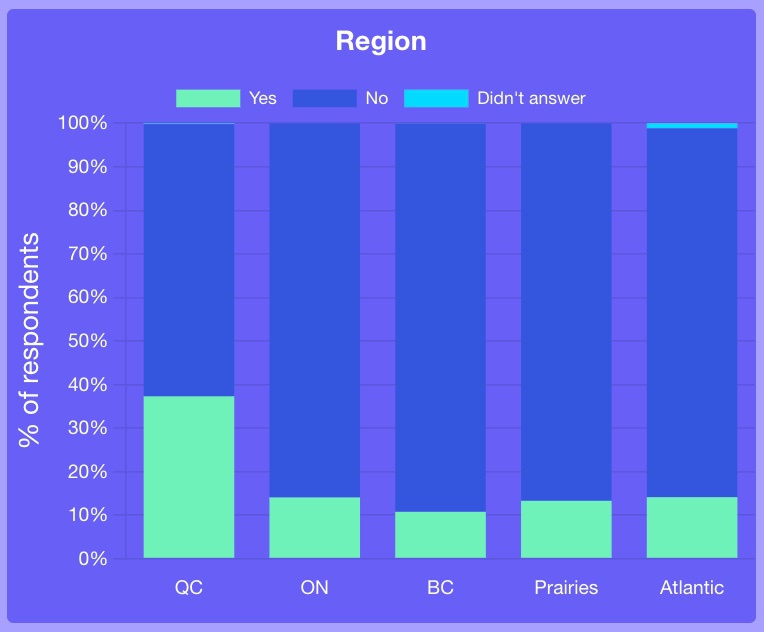

OurCare survey Q17: Did you have to pay a fee? Percentages of people with no primary care who tried to get care last time they had a health issue? (From survey section titled Those without a family doctor or NP. Select the question from the dropdown menu).

OurCare survey Q17: Did you have to pay a fee? Percentages of people with no primary care who tried to get care last time they had a health issue? (From survey section titled Those without a family doctor or NP. Select the question from the dropdown menu).

Survey results also suggest that Quebecers are strongly supportive of new models of practice that prioritize accessibility and convenience for patients: 85 per cent say the multidisciplinary health-care teams should be reorganized to operate like the public education system, accepting anyone living in the neighbourhood (72 per cent for all Canadians); 73 per cent say they are supportive of that model even if it means changing providers when moving neighbourhoods (66 per cent for all Canadians). Another striking difference is that Quebecers seem to prioritize the personal connection with their primary-care provider less than other Canadians. Only 49 per cent consider it very important that their family doctor or nurse practitioner “knows them as a person” in contrast to 65 per cent for all Canadians. This most likely is driven by the longstanding challenges in access to primary care.

OurCare survey Q51: Do you think teams of family doctors and nurse practitioners in Canada should have to accept as a patient any person who lives in the neighbourhood near their office?

OurCare survey Q51: Do you think teams of family doctors and nurse practitioners in Canada should have to accept as a patient any person who lives in the neighbourhood near their office?

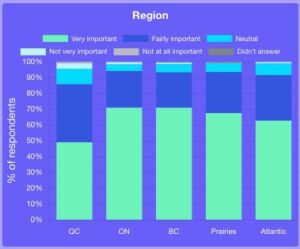

OurCare survey Q25: When you think about getting care from a family doctor or nurse practitioner and the practice they work in, how important is the following to you? “They know me as a person and consider all the factors that affect my health.” (From survey section titled What is important when it comes to primary care. Select the question from dropdown menu).

OurCare survey Q25: When you think about getting care from a family doctor or nurse practitioner and the practice they work in, how important is the following to you? “They know me as a person and consider all the factors that affect my health.” (From survey section titled What is important when it comes to primary care. Select the question from dropdown menu).

While Quebecers demonstrate strong support for new models of practice, such as neighbourhood access to primary-care providers, recent changes aimed at improving access, such as the “single point of access for unattached patients while they are waiting for attachment” (Guichet d’accès à la première ligne) and the collective enrollment to family medicine groups (GMF) instead of family physicians, have been met with both enthusiasm and concerns. Some primary-care professionals have expressed concerns that these changes may challenge the continuity of care and longitudinal follow-up with their patients, potentially leading to a breakdown in the patient-provider relationship.

Balancing the urgent need for equitable access to primary care with the importance of maintaining relational continuity and comprehensiveness of care is a critical challenge for policymakers in Quebec. Prioritizing solutions to the current primary-care crisis in Quebec and the rest of Canada requires us to engage directly with patients and the public.

Over the coming months, OurCare is hosting Priority Panels in five provinces, each comprising approximately 35 members of the public who are demographically representative of the region. The Quebec priority panel has been meeting since April and their deliberations will culminate at the end of May with draft recommendations on how we can do better. We hope policymakers are listening.

The comments section is closed.