A healthy smile should not be dependent on socioeconomic status.

For decades, fluoride has been hailed as a champion in the fight against tooth decay among people from all social backgrounds. Its introduction into municipal water supplies in the 1940s marked a watershed moment in preventive dentistry.

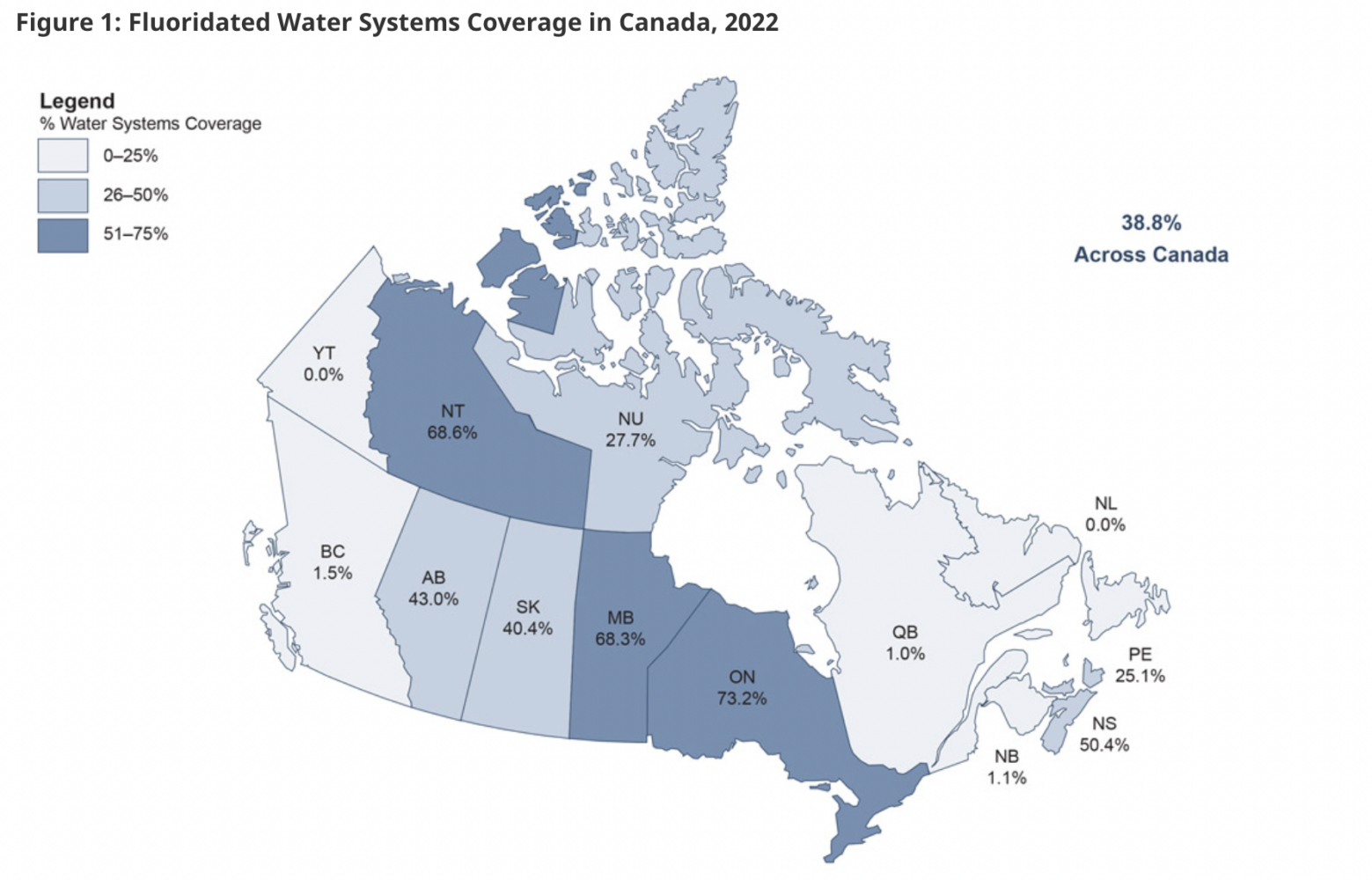

Yet, community water fluoridation systems covered only 38.8 per cent of Canadians in 2022 (another 1 per cent have access through wells with naturally occurring fluoride); since 2017, several Canadian municipalities have discontinued adding fluoride to drinking water.

The cessation of community water fluoridation has undoubtedly left a gap in the oral health landscape, particularly among vulnerable populations. Children from lower-income households have borne the brunt of this decision, with a 10-year retrospective review of Montreal emergency departments indicating dental problems being a major reason for visits. According to an Inuit Oral Health Survey, more Inuit in Canada reported poor oral health and higher frequency of oral pain when compared to non-Indigenous Canadians..

In a world where chronic diseases reign supreme, the battleground for our health often centres on what we put into our bodies. The harmful effects of sugar consumption have not only led to a startling increase in the number of medical conditions but has also increased the risk for dental problems, especially dental cavities. It’s high time for us to acknowledge that the impact of what we eat extends beyond the dinner plate to what we drink, including the water from our taps.

From its origins in naturally occurring water sources to its artificial supplementation, fluoride has consistently demonstrated its prowess in safeguarding dental health. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention considers community water fluoridation to be one of the 10 greatest public health achievements of the 20th century. The plummeting rates of tooth decay in fluoridated areas speak volumes about its effectiveness. Major public health bodies, including the World Health Organization (WHO), the Canadian Dental Association, and the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). The Chief Dental Officer of Canada and the Chief Public Health Officer of Canada have co-signed the PHAC position statement on fluoridation.

According to a PHAC 2022 report, several Canadian municipalities discontinued water fluoridation between 2017 and 2022, mostly in Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Quebec. The rationale apparently comes from studies from Mexico and Canada casting doubt over fluoride’s halo. These studies suggested a potential link between systemic fluoride intake and neurotoxicity, especially during fetal developmental stages. Though evidence remains inconclusive, it has provided ammunition for critics of community water fluoridation.

In 1984, the World Health Organization (WHO) conducted a thorough review and found insufficient evidence to link fluoride to cancer or birth defects. However, it recommended a guideline value of 1.5 mg/l to minimize dental fluorosis (a condition characterized by the presence of white spots or discolouration on the teeth). This guideline value was re-evaluated in 1996 and 2004, with no evidence suggesting a need for revision.

Map of Provincial and Territorial estimates for fluoridated water systems coverage across Canada (2022) from the Office of the Chief Dental Officer of Canada, Public Health Agency of Canada. The map does not include the estimates for coverage of wells because these naturally occurring fluoride levels are often unknown. The focus is on fluoride treated water systems from which people benefit from the optimal level of fluoride to prevent tooth decay.

Map of Provincial and Territorial estimates for fluoridated water systems coverage across Canada (2022) from the Office of the Chief Dental Officer of Canada, Public Health Agency of Canada. The map does not include the estimates for coverage of wells because these naturally occurring fluoride levels are often unknown. The focus is on fluoride treated water systems from which people benefit from the optimal level of fluoride to prevent tooth decay.

Community water fluoridation for prevention of tooth decay has been endorsed by more than 90 national and international governmental and professional health organizations, including the Public Health Agency of Canada. Ontario, Manitoba and Nova Scotia are the provinces with the highest percentage of community water fluoridation systems with rates of 73.2, 68.3 and 50.4 per cent, respectively (the Northwest Territories is at 68.6 per cent) . At the other end of the scale, the lowest rates are Newfoundand and Labrador (0 per cent), Quebec (1 per cent), New Brunswick (1.1 per cent) and British Columbia (1.5 per cent).

This raises a fundamental question: Is it ethical to neglect the oral needs of the marginalized? While the affluent may have access to dental care through private insurance and the newly established Canadian Dental Care Plan removes financial barriers for eligible Canadians, prioritizing preventive measures such as community water fluoridation holds greater promise than solely focusing on treatment interventions.

Mass medicating the municipal water supply might not sit well with some, but for those without access or the means for dental care, it could mean the difference between a healthy smile and a lifetime of dental woes.

Moreover, the economic implications of fluoride cessation cannot be ignored. With dental expenditure skyrocketing (in 2019, $16.4 billion was spent on dental care in Canada, 6.4 per cent of Canada’s overall health-care expenses), the return on investment from water fluoridation becomes increasingly apparent. Even smaller towns stand to benefit, with every dollar invested in fluoridation yielding a 20-fold return, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Closer to home, Calgary is on track to reintroduce fluoride back in its drinking water supply this summer.

In navigating the fluoride debate, a delicate balance must be struck between public health imperatives and health risks. While concerns over potential risks deserve attention, they must be weighed against the tangible benefits that fluoride brings, particularly to those on the margins of society. It’s time to move beyond polarizing discussions on public health programs and engage in a nuanced dialogue that prioritizes the well-being of all Canadians.

After all, a healthy smile knows no socioeconomic boundaries.

The comments section is closed.