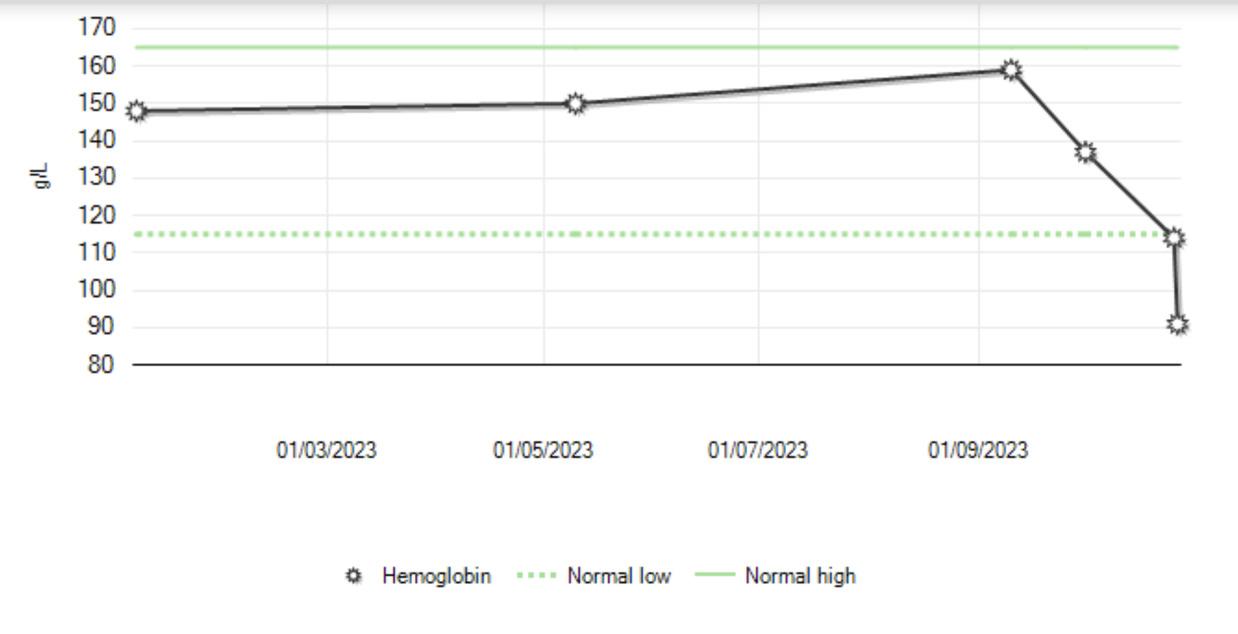

There is nothing in a textbook that prepares you for the moment you’re staring at a graph of your hemoglobin dropping. No amount of clinical experience can equip you to lie for days in a hospital bed with four tubes coming out of your body – a PICC line in one arm, a drainage tube in your abdomen, an IV in the other arm and a Foley catheter anchoring you to the bed.

As medical trainees, we spend years learning to care for patients – the intricacies of pathophysiology and evidence-based algorithms, the subtle art of breaking bad news. But absolutely nothing prepared me to be a doctor better than being a patient.

In late 2023, I was a final-year medical student. My biggest concern, like most of my peers, should’ve been CaRMS residency applications. Instead, I was hospitalized with a post-operative abdominal abscess – a large infection that formed after an emergency surgery.

One moment, I was rounding on patients on the surgical floor; the next, I was one of them. Despite trying to dismiss my high fever and racing heart as just being a “tired med student,” I was admitted to hospital and soon realized the patient sharing my room was one I had rounded on earlier that morning – there were no other beds available. I wanted to disappear into the floor.

Later, when I had enough strength to walk in that thin, crispy hospital gown, other patients would occasionally call out, “Hey, weren’t you my doctor?”

Looking away, I’d mutter “I’m not a doctor,” which, technically, wasn’t a lie.

What followed felt like a never-ending string of complications; first, the infection in my abdomen spread to my blood — Staph aureus bacteremia, a deadly infection that kills about three in 10 people who get it. I try not to think about that stat.

Even after discharge, I needed four weeks of IV antibiotics through a PICC line that snaked from my arm to my heart. The pump’s constant whoosh became the soundtrack of my recovery — I can still hear it sometimes.

When the line was finally removed, a large blood clot took its place, requiring months of blood thinners. Eventually, I began to feel like a professional patient.

It was the kind of experience that breaks something inside of you. Yet, in the cracks, something new also forms. At the time what poured out was fear, frustration and grief. It wasn’t until my body healed, and time passed, that I was able to look inward and make sense of it all.

At the time, I hated when people would stand by my bedside and say, “This is going to make you a better doctor.”

I seethed at those words.

I already had empathy. I already had resilience. Did I really need a brush with death to become a good doctor?

Looking back now, more than a year and a half later, I must admit they were right. My time as a patient was terrifying, at times surreal, but undeniably full of enduring lessons.

Here are five of them:

- The Overwhelm of Information Overload

I could pass exams. I could recite the coagulation cascade, describe the SIRS criteria, draw anatomy. But none of that mattered the day I stared blankly at the home care nurse as she explained – yet again – how to flush my PICC line.

I nodded, but the information flew in one ear and slid out the other. I couldn’t retain anything. Not because I didn’t care, but because my brain was overloaded.

That moment showed me that even the most medically literate patients can feel completely lost. It’s not ignorance; it’s overwhelm – a totally natural response to illness and trauma.

Now, when I counsel patients, I think of the blank expression I must have given that nurse. I slow down. I pause. I check in. I always try to remember how it feels to be on the other side of the explanation – scared, tired and hanging on by a thread.

- The Power of a Seat

In medical school, we are taught about a well-known study showing that when doctors sit instead of stand when talking to patients, these patients feel they’ve spent more time together — even when the actual visit is the same length.

Intellectually, I knew this.

But it is one thing to know a fact; it is another to live it.

Every morning, my infectious disease doctor would sit beside my bed. He always came straight in from the cold, still in his winter coat, before even stopping by his office. He didn’t rush. He looked me in the eye. He let me rant over and over about how I had to get back to writing my CaRMS applications. He held my hand and told me he’d do everything he could to get me better – and he did.

Studies show that patients care about feeling cared for, sometimes more than the actual care they received.

That image, and the feeling of his care, is burned into my memory – him seated beside me, holding space for me and my fears with compassion and patience.

Sometimes, the most healing thing a physician can do is pull up a chair.

- Continuity of Care Isn’t a Luxury; It’s a Lifeline

At one of my lowest moments in the hospital, my phone rang. It was my family doctor.

We didn’t have a scheduled appointment. She had just called.

“Danielle? I’ve been seeing CT scan after CT scan come in… At first, I thought it was a mistake. Are you OK? Aren’t you supposed to be in the middle of CaRMS?”

Yes!! I wanted to scream. I was supposed to be focused on CaRMS. I wasn’t supposed to be here.

I will never forget the sheer validation and relief of that moment.

Amid the whirlwind of seeing more doctors than I could count – specialists, residents, hospitalists – hearing the voice of someone who knew me brought me to tears. She didn’t need a chart or one-liner; she knew who I was before this illness swallowed me whole.

Continuity of care is about more than follow-up. It’s about familiarity, safety, trust; it’s human connection. In an era where fewer and fewer Canadians have access to the vital connection that is a family doctor – as many as one in four people in Ontario – we must remember that continuity isn’t a luxury — it’s a lifeline.

- Patients Feel Powerless — Even When They’re Doctors

What do you call a doctor admitted to the hospital?

Still a patient.

One day, a nurse came in to start a blood transfusion – which I had not been told about.

“Oh, I didn’t know that was happening,” I said gently. “Don’t I need to sign a consent?” I was not objecting; just curious.

Minutes later, a likely overworked resident stormed in, clearly annoyed at having been paged out of the operating room. Frustrated, the resident snapped “You’re a med student. You’ve consented patients for blood before, right? Consent yourself.”

I wish I could say I advocated for myself. But I felt small, scared and ashamed of being a “difficult” patient. I shrank into my hospital bed.

I hold tight to that memory to remember just how fragile dignity is in the hospital. From flimsy gowns to fragmented sleep, patients lose control over almost everything.

It is a lesson I carry to this day. Now, as a resident physician, I know that no physician ever sets out to dismiss or intimidate a patient, but this taught me how easily it can happen — even to someone with a medical background.

- It Takes a Village

“Do you have any supports at home?”

It’s a standard refrain of discharge planning. But after my discharge, I learned how vital the role of community is in healing.

My recovery involved everyone around me. My family, who drove hours just to sit beside me when I was too weak to even speak. My roommate, who cleared out our fridge for weeks’ worth of bags of IV antibiotics. Friends who bought me ginger ale at 2 a.m. when nothing else stayed down. Classmates who stopped by my bedside after 26-hour shifts just to check in. I couldn’t have done it without them.

Illness radiates outward; it spills into households, friendships, communities.

Support systems aren’t just helpful – they’re essential for healing. If we don’t ask who’s standing behind a patient when they leave our care, even the best medical care can fall short.

In the end, it wasn’t medicine alone that healed me; It was the people who didn’t let me face any of it alone.

—

Being a patient is undoubtedly the hardest job in the hospital. At the same time, I’m grateful for what it taught me. Not because suffering has any inherent value, but because it gave me perspective.

It reminded me that patients are more than medical cases. They’re people – often scared, often overwhelmed, always worthy of dignity and care. It reminded me that healing isn’t always linear, and that compassion and competence go hand in hand.

And that the line between “provider” and “patient” is always thinner than we’d like to think.

That’s my best friend! You are so strong Dani! What an excellent read.

Thank you. Ok if I share?

Yes, of course ! Thank you

Your excellent article depicts how simple kindnesses and common sense, so often overlooked (especially by busy, overworked professional healters), go a very long way in people’s care and recovery.

Thank you for sharing Danielle. You taught us all something very important with this article.

This was a brilliant read. I am forwarding to my trainees. Thank you for sharing.

Thank you for the kind words!

Thank you for sharing. And for summarizing your reflections so poignantly.

Thank you, Dr. Forte!

Wow, Danielle. This is a an excellent article. Every part of your insightful essay made me pause. Thank you for sharing, and showing us how best to show up for our patients, and each other. Very different to be on the other side.