Findings from COVID-19 serological studies can provide important pieces of the epidemiological puzzle but they require cautious interpretation.

Health Canada authorized the first serological test for COVID-19 to look for antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in the blood recently. While existing diagnostic tests tell us if someone is currently infected, serological tests will tell us how many have been previously infected and if they are possibly immune to reinfection. This includes people who had only mild infections and those who never developed symptoms at all (asymptomatic cases). They might also tell us how many remain susceptible, assuming prior infection confers some short-term immunity.

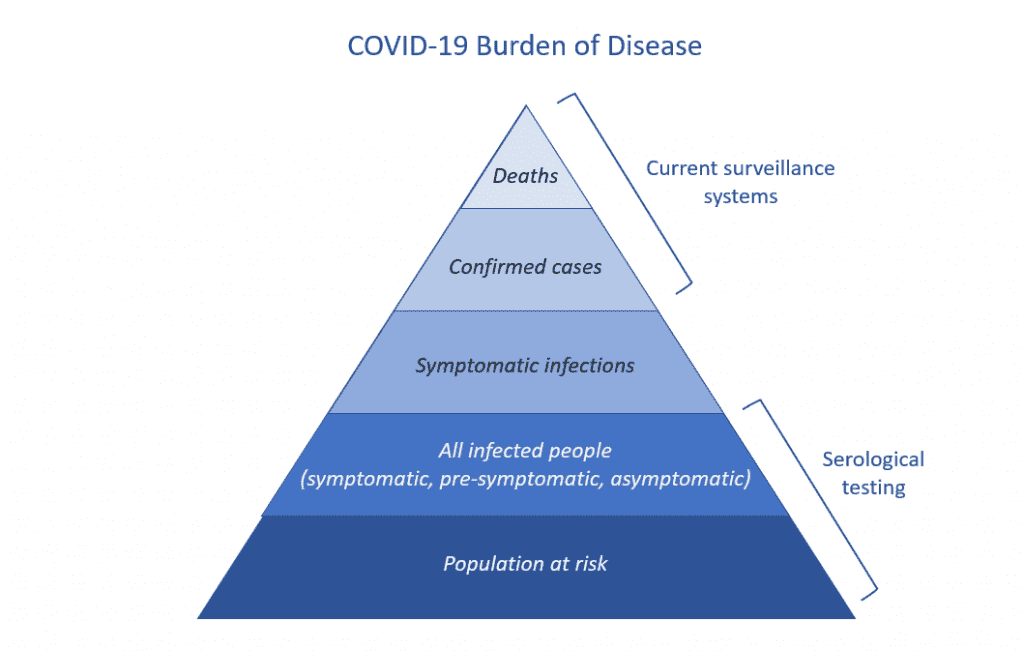

Epidemiologists are often preoccupied with getting this all-important “denominator” information. Right now, our surveillance systems only look at the  top of the COVID-19 disease pyramid: reported cases (mostly in hospital) and deaths that have been confirmed through diagnostic testing. But because of limited testing, we don’t know the size of the base of the pyramid.

top of the COVID-19 disease pyramid: reported cases (mostly in hospital) and deaths that have been confirmed through diagnostic testing. But because of limited testing, we don’t know the size of the base of the pyramid.

Knowing how many people have been infected will give us a better idea of the spread of COVID-19 in the population and can inform our public health response going forward. It will also allow epidemiologists to more accurately estimate the proportion of infected people who die from COVID-19 (the infection fatality ratio) and the proportion of infections that are asymptomatic.

Importantly, serological tests might tell us on an individual basis whether someone has immunity to SARS-CoV-2 – a critical question for policymakers as provinces reopen sectors of the economy. However, the idea of these so-called “immunity passports” has been widely criticized by scientific experts and the World Health Organization on scientific, political and ethical grounds.

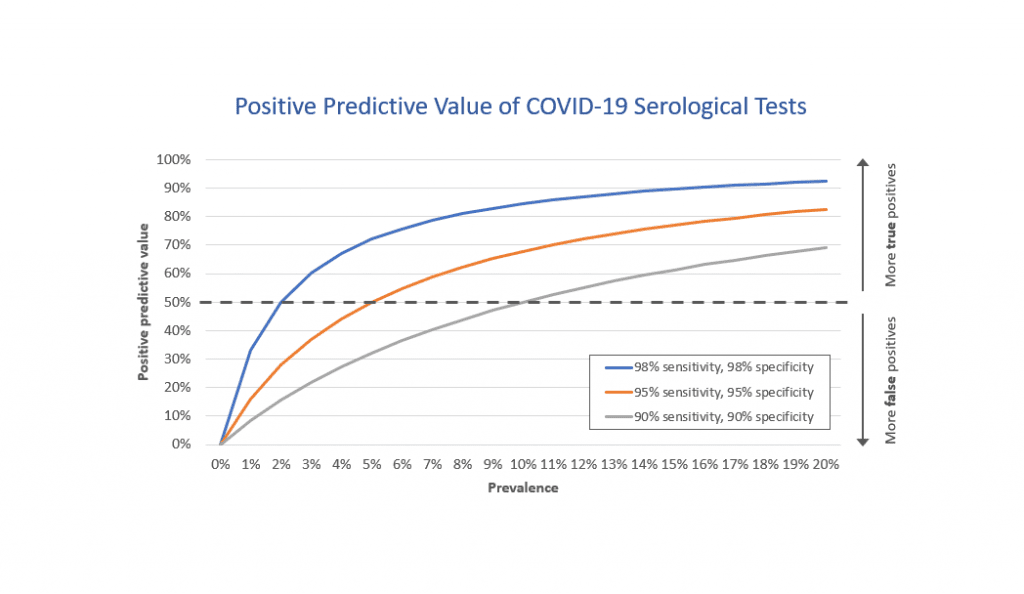

That’s because the accuracy and reliability of these tests can vary considerably. Before serological tests can be made widely available for diagnostic purposes, we need to know what proportion of people who were truly infected with SARS-CoV-2 have a positive antibody test (known as “sensitivity”), what proportion of people who were truly not infected have a negative antibody test (known as “specificity”) and how common the infection is in the population (known as “prevalence”).

Even a “good” test (for example, one with 95 per cent sensitivity and 95 per cent specificity) will have a small margin of error that when multiplied on a population scale can produce a large number of incorrect results, essentially telling people they are immune to COVID-19 when in fact they are not.

For example, when the disease is rare in a population (say prevalence of 5 per cent), even that “good” test would result in 950 positives for every 10,000 people tested. Of those, 475 people would be correctly identified as cases, but an equal number of 475 people would be false positives. Under that scenario, serological testing would be no better than tossing a coin.

Serological tests currently being used in the United States under Food and Drug Administration Emergency Use Authorization range from 87.5-100 per cent for sensitivity and 94.4-100 per cent for specificity. But other commercially available tests may be far less accurate.

There is also a lot that we still don’t know about SARS-CoV-2 immunity.

Patients who have recovered from SARS-CoV-2 infection typically mount an immune response within two weeks of disease onset but we don’t yet know the amount of SARS-CoV-2 antibody that will confer immunity to reinfection – what epidemiologists call the correlate of protection. Some point-of-care rapid tests show a red line to indicate a positive result, like a pregnancy test, but this a false dichotomy. Antibody levels occur along a continuum; someone with a high antibody titre is probably protected from reinfection but someone with a low but detectible titre might not be.

We also don’t know how long that immunity will last. It could be one to two years, similar to seasonal coronaviruses, or it could be two years or more as with the original SARS and the related MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome) viruses.

We don’t know how well antibodies targeting different parts of the virus will neutralize the SARS-CoV-2 virus or the amount of potential cross-protection from other human coronaviruses. As we’ve learned from zombie movies, not all targets are alike. Some antibodies might be the equivalent of a shot to the zombie’s head but others might just take off its arm or leg. The latter won’t be enough to stop the virus although it might slow down the attack.

Finally, there are also some infected people who will falsely test negative on serological tests either because they did not develop enough SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, especially for mild cases, or because they were tested too early in their infection and before they had enough time to develop antibodies.

The most recent evidence suggests that the proportion of people who have SARS-CoV-2 antibodies ranges from less than one per cent among blood donors in Scotland to up to 14 per cent in hard-hit areas like Heinsberg, Germany, and New York, with most estimates far below the population prevalence needed to use serological tests for diagnostic purposes. Many antibody surveys to date have also been widely criticized for selecting participants with a higher likelihood of exposure to COVID-19, under-representing minority and low-income populations, finding only a small number of positive cases and the accuracy of the tests used.

Population-based antibody surveys will fill an important gap in our understanding of COVID-19 epidemiology. But they won’t be a quick fix to the pandemic. Instead, we must continue our public health actions, including enhanced diagnostic testing, tracking of confirmed cases and their close contacts and supporting individuals to self-isolate as we move into the next phase of our pandemic response.

The comments section is closed.

Thought this is a great article which summarized the state of antibody testing for SARS-COV-2 I totally agree with your conclusions I am a clinical and molecular immunologist just getting ready to offer antibody testing in south jersey in my lab As lab director I’m recommending it as a first step towards defining immunity in patients My intensions is to expand that to include both antibodies and T cell activities in patients. There is evidence that T cells play an active role in both protecting and activating the immune system by the virus

Thank you, succinct and well targeted for me, on the thoughts I have had… and I particularly like the Zombie reference! :)