All of us can name the biggest infectious disease killer in the world: COVID-19. But do we know which infectious disease bore this title prior to the COVID-19 pandemic? It was tuberculosis (TB) – a disease that continues to take over a million lives every year and was responsible for 1.5 million deaths in 2020 alone.

Although more than 1.7 million lives were lost to COVID-19 in the same year, TB has accompanied humanity for much longer, causing suffering and death for millennia, and continues to do so today. The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted TB care worldwide; TB deaths actually increased in 2020 compared to 2019, representing the first year-on-year increase in 15 years.

Although the burden of TB is disproportionately experienced in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), it also persists here. Since Canada’s confederation, when TB was the leading cause of death in the country, the disease has remained a public health problem and progress on its elimination has been slow.

One of the major barriers to ending TB in Canada is the long-standing lack of robust national surveillance for the disease. Alarmingly, the most “recent” Canadian TB report (published in 2019), presents data on TB cases from 2017 and TB outcomes from 2016. It is now 2022, and five-year old data are inadequate for informing an evidence-based TB response. This is especially true in light of the severe disruptions that the pandemic has caused for TB programs across the country. The lack of recent data makes it difficult to accurately evaluate and mitigate the disruptive impacts of the pandemic on TB programs and their consequences for people affected by TB.

Further, Canada has committed publicly to specific global and domestic goals to reduce TB cases and TB-associated deaths, but the lack of recent data means that we cannot measure whether we are on track to meet these goals.

That is why, this year on World TB Day, we at Stop TB Canada (a network of TB advocates) have launched the Canadian TB Tracker to hold the Government of Canada accountable to the TB elimination targets it has set. Given that this year’s World TB Day theme is “invest to end TB,” it is our hope that highlighting findings from this tracker will generate impetus for Canada to invest the resources necessary to end TB, both at home and abroad.

The tracker lays bare large gaps between stated goals and the reality of TB elimination in Canada.

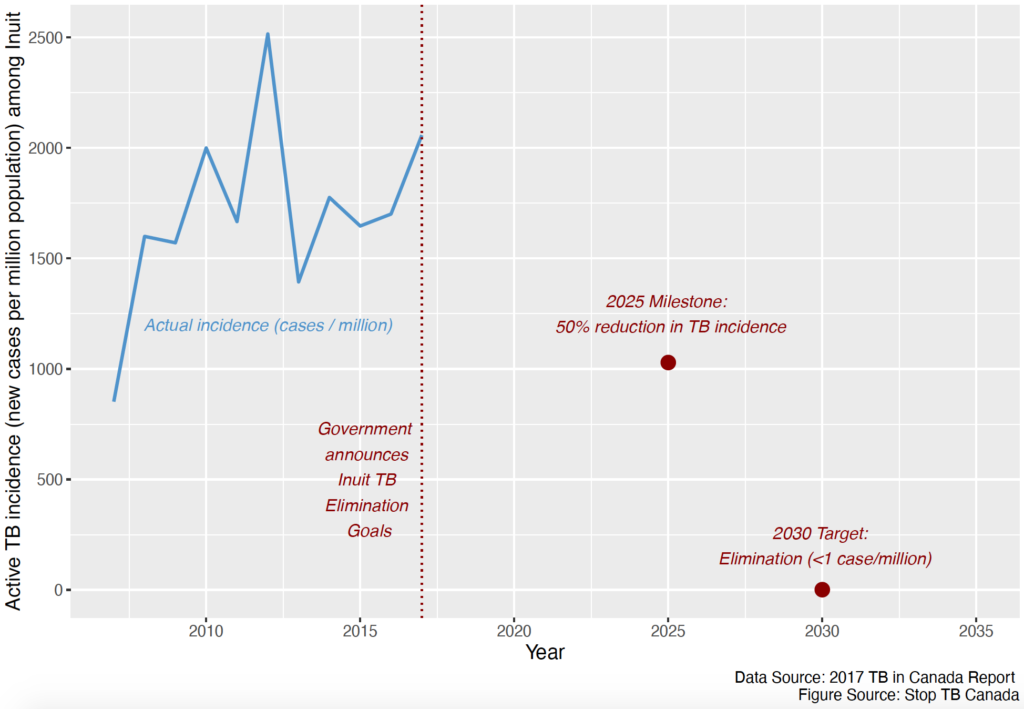

The tracker lays bare large gaps between stated goals and reality regarding TB elimination in Canada. One of the most striking of these is the lack of progress on TB elimination among Inuit. In 2017, the incidence of TB among Inuit was more than 400 times higher than among the general Canadian population. In the same year, the Government of Canada committed to eliminating TB across Inuit Nunangat (the Inuit homeland) by 2030, which means reaching a TB incidence of less than 1 TB case per million population. Fig. 1, adapted from the tracker, shows TB incidence among Inuit compared to Canada’s Inuit TB elimination targets. With an incidence of 2,058 TB cases/million among Inuit in 2017, we are far from reaching the 2030 elimination target. Alarmingly, current progress toward this target cannot be monitored given that the most recent Inuit-specific data are now more than 5 years old.

The disproportionate burden of TB among Inuit in Canada is a direct result of neglect to address the social inequities that facilitate transmission of the disease, including food insecurity, inadequate housing and inequitable access to health care. How can Canada honour the calls in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (particularly calls 18 and 19) while allowing conditions to persist that put Indigenous Peoples at higher risk for diseases such as TB, and then fail to, at the very least, measure how far we continue to fall short of stated elimination goals?

Apart from the goal to eliminate TB across Inuit Nunangat, Canada has also signed on to global TB elimination commitments to reduce TB incidence in the country as a whole. One of these is the World Health Organization’s End TB Strategy, launched in 2015, which includes a target to reduce TB incidence by 90 per cent by 2035 (compared to 2015). Again, we are not on track to meeting this target – unfortunately, the overall incidence in Canada has in fact increased since 2015.

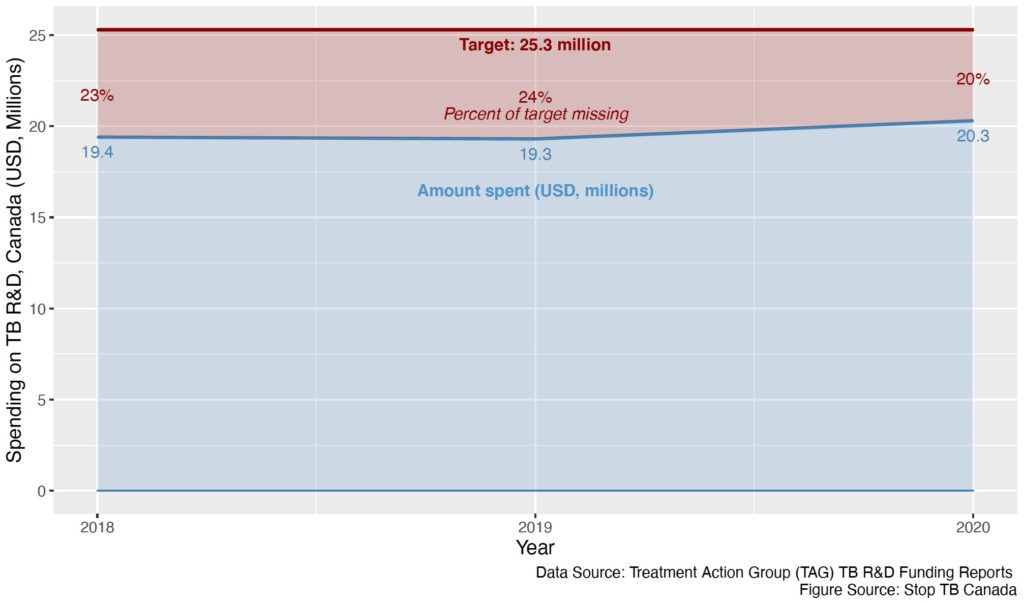

The tracker also shows Canada’s contributions to TB research and development (R&D) funding. At the first-ever United Nations High-Level Meeting on TB in 2018, member states committed to contributing their “fair share” to TB R&D funding, defined as countries dedicating at least 0.1 per cent of their overall research spending to TB. Unfortunately, Canada has consistently failed to meet this target (set at USD 25.3 million) (Fig. 2), and as of 2020, we are still falling short of it by 20 per cent. If the Government of Canada is genuinely committed to ending TB, it must invest the resources required to do so. Investing in TB R&D is not only critical to TB elimination but builds capacity to respond effectively to other infectious disease threats that rely on similar tools and systems.

Overall, the tracker underlines that if we have any hope of finally ending TB in Canada, two things are critical: The first is building a national TB surveillance system with detailed and timely TB data to plan an appropriate TB response and track progress toward its elimination; the second is to commit the necessary financial resources to support ending TB (including the resources required to bring our out-of-date surveillance system into the present).

It is disheartening that tracking progress toward TB elimination in Canada has fallen on a small volunteer advocacy group with limited resources when it is within the purview of the governmental entities that publicly committed to these goals. But the good news is that Stop TB Canada’s tracker is a powerful new advocacy tool, which everyone (including you) can use to help hold our leaders accountable to working toward TB elimination.

Together, we can advocate for ending TB in Canada, and around the world.

The comments section is closed.

I am delighted to read this article. Thank you.

Through the guidance of OLA Executive Director Edward J, O’Brien, Ontario led the way in the 1940s, 50s, 60s and 70s with thoughtful, innovative methods of diagnosis, treatment and especially volunteer community support in TB control. Supported by the Ontario and Canadian governments as well as the Canadian Lung Assc., WHO and the International Union Against TB, the Ontario TB/RD Association entered the European, Southeast Asian and Pacific Rim countries to urge, identify and assist the poorest places in the world in the fight against what was known as the ‘white scourge’. Check out the history of the Canadian Lung Association and the Ontario Lung Association. Disclaimer: my father was Edward J. O’Brien.

This is interesting to the Lyme disease community because the model for complex Lyme disease should be TB according to professor Ying Zhang. Lyme was misclassified as a minor nuisance disease when the insurance industry red-flagged it as being to expensive to treat in 1994. Current tests miss at least 1/3 of the cases and are inaccurate at the earliest acute and late stages of disseminated Lyme. The serological tests were never meant to be a definitive diagnosis, only to assist the physician in making their diagnosis and cannot be used reliably to rule out Lyme disease. Infectious disease doctors are only interested in those patients that pass the flawed test. 95% of doctors believe Lyme disease is difficult to acquire, easy to diagnose, readily cured with a short course of antibiotics. -Dr. Ken Liegner. If a patient has symptoms following treatment either initial diagnosis was wrong or they have Post Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome [PTLDS] since there is no such thing as chronic Lyme disease.

We have inaccurate data that misses at least 90% or more of new cases and have no idea of the prevalence. From Lloyd/Hawkins 2018 we can calculate Between 2009 and 2021 Canada has had between 176,854 and 850,651 cases of Lyme disease. If 20% of those cases remain ill then the prevalence numbers might range between 35,371 and 170,130 across Canada.