The COVID-19 pandemic may have shut down schools but, as new research shows, it also shut down both in-person and online bullying. And bullies are still lying low.

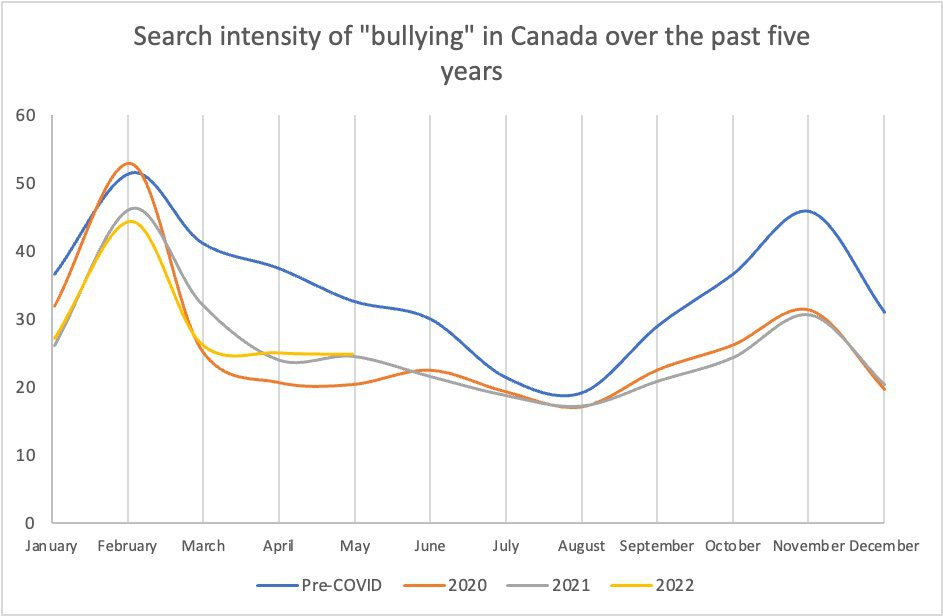

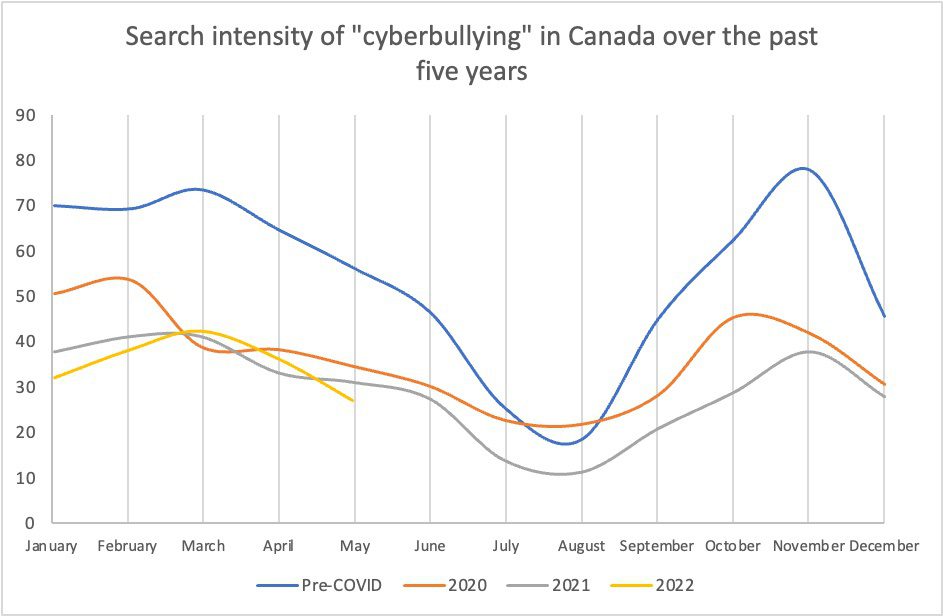

Bullying in Canada during the 2020-2021 and 2021-2022 school years was down by 28 per cent from its pre-COVID level and cyberbullying down by 44 per cent, based on Google searches for “bullying,” “cyberbullying” and similar terms.

“Schools were having to shift from in-person to remote instruction (in the spring of 2020),” says lead researcher Andrew Bacher-Hicks, an assistant professor of education at Boston University. “A lot of people were concerned that cyberbullying was going to take off.”

After all, students would be reachable on their electronic devices all day. Bullies might be able to send messages to their victims through learning platforms without teachers’ noticing – and victims would have no reprieve.

In fact, online bullying declined, according to Bacher-Hicks and his colleagues.

The researchers used Google Trends to measure the popularity of terms related to “bullying” and “cyberbullying.” This method has been used before to predict voting patterns, stock prices and a variety of public health outcomes from flu outbreaks to suicide rates.

Google Trends has the advantage of measuring this in real-time. Researchers could see how often bullying was searched for as it was being searched for; asking students in a survey would mean a time delay that could play tricks on their memories. Google Trends is also all-seeing: students can lie in a survey, but they can’t lie to a search engine.

Bacher-Hicks and his colleagues found that there was a roughly 30 per cent drop in the prevalence of searches for terms related to “bullying” and “cyberbullying” in the United States after the start of the pandemic.

Applying their methodology to Canadian data, searches for “bullying” fell by roughly 40 per cent in the three months after lockdown and online learning began – that is, until summer holidays – compared to the same period pre-COVID.

Searches for “cyberbullying” were already down by roughly 25 per cent in the first couple of months of 2020, again compared to the same months pre-COVID. After the pandemic started, they also fell by more than 40 per cent.

And even though schools started returning to in-person learning (with starts and stops) in September 2020, searches for “bullying” and “cyberbullying” have remained low and have not returned to their pre-pandemic levels.

(The peaks in searches about “bullying” in February and November are due to two anti-bullying initiatives, Pink Shirt Day and Bullying Awareness Week, and not to seasonal spikes in bullying activity. Search popularity doesn’t perfectly match how often bullying or cyberbullying occurs.)

The drops surprised Bacher-Hicks, whose research focuses on measuring teacher impact and on the links between crime and education. But it didn’t surprise many of the bullying specialists to whom he reached out.

“The same individuals – both in terms of the victims and the aggressors – are involved in in-person bullying and cyberbullying,” says Bacher-Hicks. “Others have noted that in many cases … online bullying is an extension of in-person bullying that’s happening during the school day.

“If you reduce in-person bullying, you may also be able to reduce cyberbullying without doing anything specifically about cyberbullying.”

Why hasn’t bullying risen more since students have gone back to school?

Why hasn’t bullying risen more since students have gone back to school?

“Some of the key changes that were put in place (in the autumn of 2020) were things to prevent the spread of COVID from one student to another,” says Bacher-Hicks. These changes included social distancing and adding more structure to the school day, to have less unstructured time in the hallways and during lunch, for instance. Reducing these interactions also reduced bullying.

This opinion is shared by Tracy Vaillancourt, a professor of education at the University of Ottawa. Along with her colleagues, Vaillancourt surveyed more than 6,000 Canadian students between Grades 4 and 12 and found that they reported less bullying after the pandemic started. She says that the key to tackling bullying is increased supervision.

“You can see when things are going wrong with students when you have a reasonable number of them to attend to. But if you have two teachers for 300 students, you’re not going to notice when things are going amuck.

“We just need more adults monitoring students during non-classroom time.”

This doesn’t mean that adults will act like Big Brother; reinforced adult presence should not result in social isolation and shrunken friendship circles. “Positive relationships will flourish,” says Vaillancourt. “I don’t think there’s anything that supervision will do to thwart that – but supervision does thwart bullying.”

The Durham District School Board, east of downtown Toronto, has a policy of making adults visible around the school.

“The more positive a (school) climate is, the better (the) chance of less bullying happening,” says Gary Crossdale,” superintendent of its Positive School Climates department since 2020. It starts with the principal, who sets the tone in his or her interactions with other staff members – not just teachers but also secretaries and caretakers, for example – who then transmit this down through their own interactions with students.

When school was in-person (and now that school has returned to being in-person), principals and other adults can be found outside at recess or greeting students at the door; when it was online, they would pop into virtual classrooms. All of this establishes trust and meaningful relationships, and it makes students more comfortable reporting instances of bullying, Crossdale says.

“School is one of the greatest stabilizing features in a child’s life, and adults make the best schools safe and inclusive.”

The comments section is closed.