Public health ethics state governments are responsible for monitoring and mitigating the short- and long-term consequences of COVID-19 control measures beyond reducing the number of cases, deaths and hospitalizations. This is an essential consideration as we reach a new stage in the pandemic and governments consider maintaining or loosening restrictions.

In public health, the patient is the “population” and regulations, orders and monetary disincentives (e.g., fines) are standard policy tools. This contrasts sharply with conventional “medical” ethics that focus on individual patients and their autonomy and health-care journey.

When assessing the impact of COVID-19 prevention and control measures it is important, especially for frontline health-care workers, to understand the foundational differences between “medical” versus “public health” ethics.

Health-care workers generally operate under a normative deontological ethical framework. This model is framed in what is the “morally” right thing to do, despite the outcome. That is, the means outweigh the outcome.

This is folded into the concept of informed consent. Patients capable of giving consent can decline therapy, even if it is lifesaving. This line blurs when an individual may cause harm to others and society steps in. For example, a patient with infectious tuberculosis may decline therapy but then be forced into isolation to prevent spread.

The field of medical ethics has been strongly influenced by Beauchamp and Childress’s ethical framework: beneficence (do good); non-malfeasance (do no harm); justice/equity (distribution of scarce health resources and deciding who gets what); and patient autonomy (patients’ rights to self-determination in their health-care journey). They argue that no one of these principles is paramount despite patient autonomy being commonly considered above the other principles in the general medical literature.

Public health ethics involves a subset of normative consequential ethics, i.e. a utilitarian framework. In utilitarian ethics, the ends justify the means when utility is maximized overall. In other words, “the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the one.” This is further refined by adopting a combined utilitarian and Rawlsian approach, the latter of which focuses on distributive justice such as focusing on preventing harm to the most vulnerable.

Taking this one step further, there is a responsibility for the state to follow ethical principles when it imposes restrictions on individual freedoms and charter rights, as is the case during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ross Upshur published a set of principles in 2002 to guide the imposition of such public health directives. They include: Mill’s harm principle, transparency, using the least coercive means possible and equity.

As originally described by Mill, his harm principle reflected that: “The only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community against his will is to prevent harm to others. His own good, either physical or moral, is not a sufficient warrant.”

This fits with the classic cliché: “Your right to swing your fist ends where my nose begins.” During COVID times, this could be: “You have the right to be infectious as long as you do not infect anyone else.”

This dovetails with the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which entrenches individual rights relative to mobility, association, peaceful assembly and speech “… subject only to such reasonable limits prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society” (Section 1).

Quarantine, isolation, indoor and outdoor group size caps, travel bans and mandatory mask use are examples where the state has to demonstrate that such impositions on individual freedoms are directly linked to preventing or reducing risk to others. This is not to argue that such measures are not needed, or that they do not necessarily work. However, in a free and democratic society the state has a duty to provide compelling information and data to back up its orders. If the latter is provided, compliance may be improved. This links to the second principle of transparency.

Releasing information should go beyond the frequent bureaucratic justification of releasing information “only if needed for public safety,” and the press (e.g., Winnipeg Free Press, CBC) has been critical of the apparent lack of transparency.

Transparency helps individuals link restrictions on their freedoms to the tangible protection of society.

For example, if the public were better informed about the breakdown of disease transmission sources (e.g., worksites, acute care, PCH, community, house parties, etc.) individuals may make better risk reduction decisions and be more compliant with prescribed public health orders.

In addition, transparency helps to establish trust in the government. The paternalistic “we got this” or “trust us” platitudes have no place in a 21st century democracy, especially during a pandemic.

A prime example of a lack of transparency is Manitoba’s refusal to release provincial Personal Care Home (PCH) inspection reports. Prior to the pandemic, family and friends could visit their loved ones in PCHs and directly observe how well, or not, they were being cared for. During the PCH “lockdown,” it is hard to imagine the angst and fear they felt as they watched media reports on multiple PCHs in Manitoba and around the nation.

Using the least coercive means possible is self-explanatory. Start with education and information and move to progressive measures to achieve compliance with justified impositions on individual freedoms.

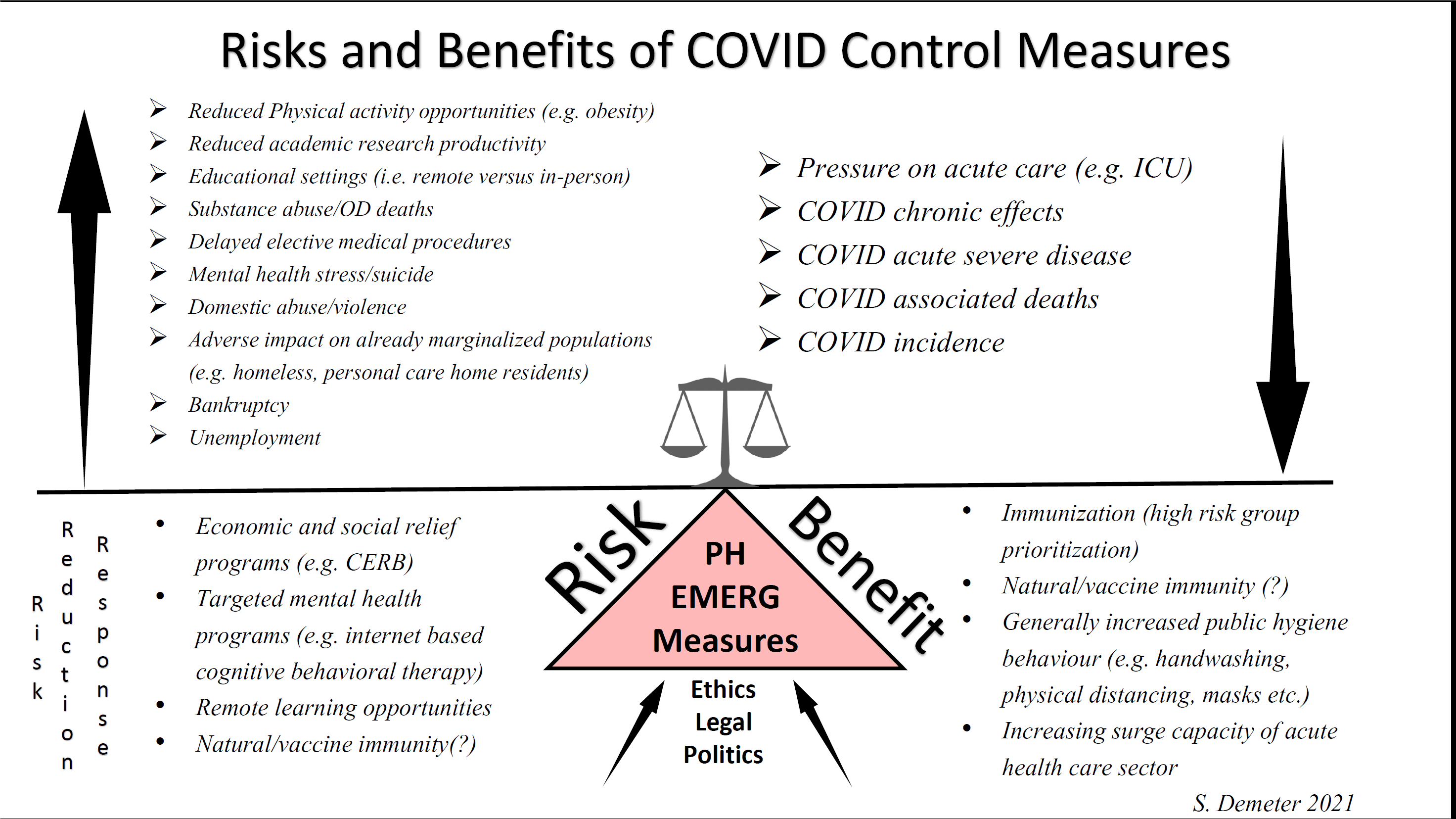

Fixating on “flattening” the curve at all costs avoids the uncomfortable reality that such preventive measures also cause harm, especially to marginalized groups such as the homeless, low-income families, PCH residents, those living with disabilities and those with mental health challenges, to name a few.

This sentiment has recently been echoed by the Public Health Agency of Canada.

The reciprocity principle states that the government should provide individuals and communities with the resources and means to achieve compliance with public health or emergency-measures directives. Salary, rent, small business and other monetary compensation programs are good examples of attending to this principle. Maintaining essential services for groceries, gas and daycare are other good examples.

Many health-care unions have raised concerns about inadequate resources or access to personal protective equipment (PPE). The Ontario Health Coalition raised concerns that a lack of adequate PPE is related to the incidence of infection in health-care workers.

It is interesting to note that B.C. has adopted an Ethical Decision-Making Framework that includes, and significantly expands upon, Upshur’s framework. It includes the following elements: respect, harm principle, fairness, least coercive and restrictive means, working together, cooperation, reciprocity, proportionality, flexibility and procedural justice.

Health-care policy makers face extraordinary COVID-related challenges. Pandemic control strategies, especially those that impact on personal freedoms of mobility and association, can have significant adverse socio-economic, educational and lifestyle consequences not directly related to COVID-19. Governments need to appreciate this and utilize established public health ethical frameworks to guide the imposition of such restrictions.

The comments section is closed.