In Ontario, specialists are concentrated in larger cities, and Ontarians living in smaller cities and rural regions have challenges accessing specialist services.

In Ontario, Local Health Integration Networks (LHINs) use non-financial incentives to try to attract specialists to practice in hospitals that serve rural areas, and provide telemedicine and outreach clinics for patients.

In contrast, Germany has introduced a new law with stronger central planning and financial incentives to encourage specialists to practice outside large centers.

Ontario is over twice the size of Germany in terms of land mass, and differs widely in terms of geography and population density. In Ontario, the majority of the population is concentrated in the south, with very sparsely populated communities scattered across the vast, remote north. In Germany, while the population is concentrated in urban areas, there is quite a bit of settlement throughout the countryside, with vilages and towns throughout the more rural regions of the country.

Nevertheless, there are some regions of Ontario, concentrated in the south, that are similar to Germany in that they have smaller communities that share similar challenges of access to specialist doctors as the German countryside. In collaboration with colleagues from Germany, healthydebate.ca reviews recently-introduced German legislation that is meant to improve access to specialists in the German countryside, and asks whether there are lessons for some rural regions of Ontario.

Where specialists practice in Ontario

Of the nearly 25,000 doctors in Ontario, a little more than half are specialists. Specialists tend to practice in large urban centres and university-affiliated teaching hospitals, where they have access to hospital resources such as diagnostic and laboratory services, operating rooms and inpatient services. This is generally appropriate, as smaller centres lack the volume of patients with specialized needs that larger centres have.

However, Canadians living in smaller communities, or in remote or rural areas have well documented problems in accessing specialist health care services. These people tend to have to travel longer distances to access specialists, or access these providers remotely. This problem of access is further exacerbated by higher rates of long-term disability and chronic illness. For example, rates of obesity and chronic diseases are higher in remote and rural areas of Ontario. A recent report by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences found that in areas of the province where diabetes rates are the highest, access to resources, such as endocrinologists, to provide care for people living with diabetes, is more of a challenge.

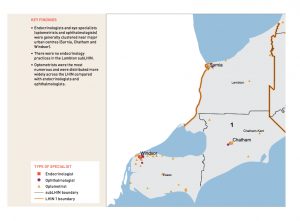

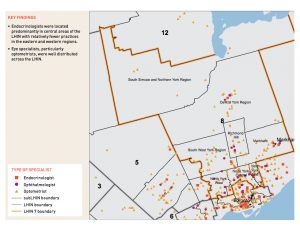

The prevalence of diabetes in the Erie St. Clair Local Health Integration Network (LHIN) region is slightly higher than the rest of the province. There are 174 endocrinologists in Ontario, with 7 of them practicing in the Erie St Clair LHIN. This region is home to an estimated 650,000 people, about 5% of Ontario’s population. The Toronto Central LHIN, is home to just over 1,000,000 people, about 9% of Ontario’s population, and has 62 endocrinologists. In the Toronto Central LHIN there are 8 large university-affiliated teaching hospitals, as compared to Erie St. Clair where there are two university-affiliated hospitals. There is about 6 times the number of endocrinologists per capita in the Toronto Central LHIN when compared to Erie St. Clair.

Click on the two maps below from the ICES Report Regional Measures of Diabetes Burden in Ontario to see the distribution of endocrinologists in the Erie St Clair LHIN, and Toronto Central LHIN.

An article published on May 18 in the Windsor Star notes that “using provincial benchmarks … Windsor is short about 100 specialists.” Windsor is the largest urban centre in the Erie St Clair LHIN, and specialists who practice in Windsor serve patients throughout the southern and eastern communities of the LHIN. Ken Deane, CEO of the Hotel Dieu Grace Hospital in Windsor notes that that there are number of programs and incentives in place to attract and retain specialists to the hospital. This includes establishing the Hotel Dieu Grace Hospital as a satellite site of the Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry at Western University. Deane says that “medical student training and increasing residency positions is part of a broad strategy to ensure specialists stay after their training, or can be attracted back to Windsor and other areas” if they are originally from the region.

An article published on May 18 in the Windsor Star notes that “using provincial benchmarks … Windsor is short about 100 specialists.” Windsor is the largest urban centre in the Erie St Clair LHIN, and specialists who practice in Windsor serve patients throughout the southern and eastern communities of the LHIN. Ken Deane, CEO of the Hotel Dieu Grace Hospital in Windsor notes that that there are number of programs and incentives in place to attract and retain specialists to the hospital. This includes establishing the Hotel Dieu Grace Hospital as a satellite site of the Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry at Western University. Deane says that “medical student training and increasing residency positions is part of a broad strategy to ensure specialists stay after their training, or can be attracted back to Windsor and other areas” if they are originally from the region.

Gord Vail, Chief of Staff at Hotel Dieu Grace agrees, noting that attracting specialists who are originally from the region has been one approach as “people tend to gravitate closer to home, family ties or partners who have jobs in the area.” Roger Strasser, Dean of the Northern Ontario School of Medicine says “the research evidence shows that the factor most strongly associated of going into rural practice is a rural upbringing, the second is positive clinical and educational experiences in rural settings.”

However, is it sufficient to rely on social ties and links to medical schools to ensure access to specialists for Ontarians living outside of large centres like Toronto? Hospitals generally post positions for specialists based on need. However, the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care does not get involved in the direct hiring or recruitment of specialists to specific areas. This can be challenging for LHINs who are charged with planning health care services in a region, but lack the authority to determine where specialists can practice.

In the absence of more authority to attract specialists to the region, Ralph Ganter, who is the Senior Director of Planning for the Erie St Clair LHIN notes that the LHIN has programs in place such as telemedicine to try to facilitate access to specialists based in Windsor for people living in the region. Gord Vail notes that some hospitals located in smaller communities run outreach clinics for specialized services like oral surgery and cardiology tests once a month, so that people in their communities do not have to travel to larger centres to access these services.

‘Bedarfsplannung’ and the German Attempts to Improve Access to Specialists in Rural Areas

Germany has taken a different approach in an attempt to improve access to specialists in rural areas. Given that nearly one in four doctors in Germany will be reaching retirement age in the next five years, and the growing concentration of specialists in urban areas, the German government recently updated a law known as ‘Bedarfsplanung’. Bedarfsplanung, which translates into English as “supply management plan”, is a nation-wide approach to planning where specialists in Germany can practice.

Legislation governing the German health system was put in place in 1913 and is revised every few decades in response to ongoing changes to the system. Until recently, the legislation was last revised nearly 20 years ago because of circumstances the exact opposite of the current situation. At that time there was an oversupply of doctors in Germany, and the government limited physicians’ ability to bill the public-insurance funded health care system as well as restricted the number of various specialists from entering regions where it was determined that their specialty was over-represented. To learn more about the German health care system click here.

However, twenty years later there are now a growing number of vacant medical practices, particularly in rural areas of Germany. One half of patients living in rural areas have to travel to urban centres for medical treatment. Uneven specialist supply through the country has received a great deal of attention in the media and garnered prominence as a political issue. Many local mayors from rural areas exerted pressure on the national government to improve access to specialists in their region.

Bernhard Gibis, a researcher at the German National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians described this as “an emotional debate about giving the countryside more attention… to make sure it isn’t further left behind.” Gibis noted that rural regions of Germany have become destabilized in the last few decades by urbanization, closure of industry and population shifts, particularly of younger people leaving for cities. This has left rural areas worse off economically and with much older populations.

The Bedarfsplannung law was revised in January of 2012 as a response to these concerns. It was developed by the coalition government in consultation with the Federal Joint Committee (G-BA), a board of doctors and members of hospitals and social health insurance funds.

Bedarfsplannung, includes stronger government control over where specialists can practice by creating defined planning areas that consider population size, age and disease status, as well as health care infrastructure to determine the number of specialists in each region. In addition, the Sick Funds legislation that required doctors to live within a certain distance from their practice area and take a mandatory amount of emergency department coverage and call, were removed. In place of these abolished practice restrictions, the new law has focused on financial incentives by paying doctors who practice in rural areas a per-patient financial incentive.

Overall, this new law has been well accepted by doctors and their associations, and it is estimated that it will infuse an additional $460 million into rural doctors’ incomes across the country.

In spite of the enthusiasm for the law, many experts doubt that these financial and planning efforts will be sufficient to lure doctors back to practice in rural regions. The German Medical Association, for example, suggests that the impact of the law will likely be blunted because payments for services in urban regions were not decreased. The AOK, one of the largest Sickness Funds in Germany agrees, noting that without reducing high-cost services and providers in urban centres, this infusion of resources to rural areas may not be sustainable.

Klaus Jacobs, who is the CEO of AOK’s scientific institute, is sceptical that “bureaucratic” approaches are sufficient to address broader social barriers that prevent specialists from setting up practices in more rural regions, noting that the appeal of financial incentives clashes with the more vibrant cultural life, as well as the better education for children and job opportunities for spouses, that urban areas offer.

Gibis agrees, saying “The law is putting in place pragmatic measures to make practice in the countryside more attractive, but there’s some hubris to think that planning can counteract this societal issue.”

Different Approaches, Shared Challenges

While Germany is tackling access to specialists in rural areas through legislation, Ontario has taken a different approach through setting up medical schools and resident training in hospitals servicing rural regions. Hospitals and LHINs are taking a lead on innovative programs, such as partnerships with medical institutions and clinics, aiming to attract specialists to hospitals that provide care for people living in rural areas.

Roger Strasser notes that “culture in Germany is very different from culture in Canada – imposing restrictions on where doctors can practice has been tried in Canada and only found to have limited effects. On the other hand, planning at the local level with communities and building from the ground up is more effective in the Canadian context.”

Can Ontario learn anything from Germany’s approach?

The comments section is closed.

I think the main impact is desired life style and opportunities for meeting the spouse’s professional

ambitions.

I belief the trouble starts at the beginning – in the selection of candidates for medical school. By picking only the highest of the high achievers, people that are driven, looking to develop themselves into the next super-star, we are not bringing up enough physicians that would be happy to move to the country and settle into a practice or hospital that provides little opportunity for development. I firmly belief that it takes bright people to become doctors, but I feel that selection criteria need to be adjusted to train doctors that will be happy in those rural settings. Selcetion of students must include those that appreciate and enjoy the virtues of a small community, that will be genuinely happy to pursue a practice in such a setting.

On that note, I do not belief that forcing doctors (such as internationally trained physicians) into these settings is the right thing to do, either.

I agree this is likely a piece of the puzzle, yes. This might be part of why NOSM graduates far more people into family med programs (as a fraction of the class size). In general, medical schools talk a good game about non-academic criteria but have not done enough yet to shift the focus away from GPA, etc. You tend to end up with people who are “deep but narrow,” keen to master medicine but not overly aware of societal context.

My perspective on this is as a medical student based in Windsor, but who is not from there.

My way of thinking about this problem is to divide specialists into two categories. The first category are those “procedural” specialties, whose practices are in some way or another linked to OR time, dialysis machines, endoscopy suites, or other equipment that they have no control over. For these specialties, the rate-limiting factor in their recruitment is whatever equipment they need. In other words, they will go where the jobs are, and, generally speaking, there aren’t enough jobs to go around in these fields. If the government wanted to attract more nephrologists to Windsor, for example, all it would need to do would be to add more dialysis machines. If it wanted more neurosurgeons, all it would need to do is add more OR time.

On the other hand, you have the “non-procedural” specialties, such as endocrinology or psychiatry. For these folks, their ability to practice and the nature of their practice remains more or less the same no matter where they are in the country. Unless they are some kind of sub-sub-specialist, an endocrinologist does pretty much the same job in downtown Toronto as they would in Essex County. Therefore, if you’re not from the region, what’s the motivation to move to Essex county? These specialties are not always totally immune to the effects of infrastructure, however. For example, the opening of a new chronic care facility at the Western Campus of Windsor Regional Hospital has gone some way to making a dent in our massive shortage of psychiatrists.

I grew up in a city of 400 000 and, to me, Windsor (population ~ 200 000 and shrinking) feels small. It’s very difficult for me to imagine myself being happy in a place smaller than the one where I grew up. This is despite the focus that UWO puts on rural medicine and the two very positive rural medicine experiences I have had to date, one in Chatham and the other in Alexandria (close to Ottawa). The only classmates I know of who are considering returning to practice in the area are those who grew up here. An increase in residency positions or mandatory rotations specifically tied to Windsor would probably make a difference, as the transition from residency to practice is probably a clearer one than the idea of returning after residency (completed elsewhere).

Faced with all of these challenges, would additional money help? Well, sure it would. For enough money, you can get people to do anything. But it be cost effective? Would it be worth it? Who knows?

First of all, great article!

As much, I would sway more to the side of providing incentives that improve the quality of life and family support for doctors, the financial incentive is unarguably an effective short term approach. Therefore, I think the benefits from both the approaches would let us go a step further is dealing the specialist supply problem.

This supply issue is one that needs to be tackled by not just Ontario but other provinces as well. Even though there are a number of rural in each province, not every area has the same population size, age, disease level and health care infrastructure as the article pointed out.

Therefore, while using the Ontario way as the base line for all rural areas, some sort of financial incentive could be given to areas that are most vulnerable. May be the least 5 or something. This would hopefully help with the immediate shortage issue while giving time for the long-term effects to take place. Since health care policies would obviously need to be adjusted with changing economy and people, the financial incentive can stop in the future. As I stated, using money to solve problems such as these would only solve problems for a short term. Any province or country would have to eventually thing about the long-term care and effects of their actions instead of trying to place a bandage and hoping that it would help.

Once again, this is only my humble opinion. I would love to know what you guys would think!