Every patient, young and old, who enters the hospital where I work needs to have a discussion with their physician about how far the medical team should go in attempting to revive them in the event that they stop breathing or their heart stops pumping. The results of this discussion are known as their ‘code status’, which is recorded at our hospital on a deceptively simple form: three separate check boxes state ‘Full code’; ‘Do Not Resuscitate (DNR)’; and ‘Other’ with a space to write in custom resuscitation orders.

This policy is meant to promote patient autonomy in making individual choices for their care. But sometimes, improperly guided code discussions create the potential for patient harm through the creation of ‘partial DNR’ orders with questionable therapeutic benefit.

I’ve experienced this personally as a medical student, where my inexperience with end-of-life conversations has sometimes led discussions with patients to devolve into a menu-like presentation of the types of interventions that are possible – a sort of a la carte approach to determining my patient’s code status. And I don’t appear to be alone – research shows that hospitals are experiencing this type of situation more frequently these days.

While a patient may voluntarily agree to a ‘variety menu’ of proposed treatments, partial DNR orders raise questions surrounding the validity of this agreement. In order to obtain informed consent, physicians should ensure that patients understand the severity of their illness and the nature of how advanced cardiac life support is performed.

A patient who suffers from severe end-stage disease, but expects to make a full recovery from a cardiopulmonary arrest, and opts for chest compressions while refusing the use of a breathing tube, misunderstands the nature of CPR and its components that are necessary to provide true benefit.

It is important to realize that most patients have only seen CPR on TV. They don’t know about broken ribs, endotrachael tubes, or the risk of permanent disability. Getting informed consent means talking to patients about their misperceptions, and explaining the real risks, benefits, and likely outcomes. This isn’t easy, especially because most patients I have encountered think their chance of surviving resuscitation is greater than 50%, when in reality it is closer to 15%.

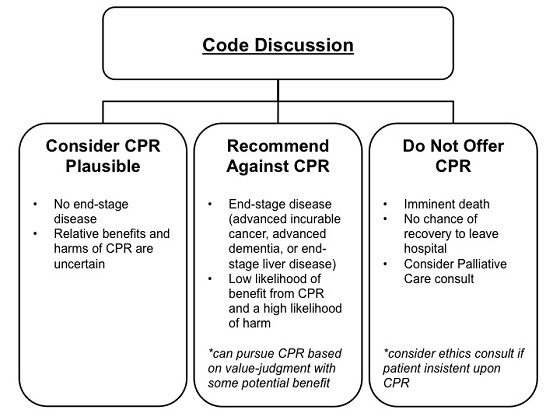

Ultimately, physicians should make a recommendation about CPR that is consistent with the patient’s goals of care (which comes from the initial aspects of the discussion with them). And instead of offering patients individual items within a CPR protocol, physicians should instead group interventions according to their intended goals of care. When having these code discussions, the options offered by the physician should change as the likely proportion of burdens to benefits increases, including the possibility of not offering CPR to a patient:

Adapted from Blinderman CD et al. JAMA 2012

Of course, the best approach is for these discussions to happen before a patient ever steps foot in hospital. We need to promote a system where advance care planning occurs between family physicians and their patients, who will help normalize the subject and raise it before they are faced with an acute illness. Patients should be reassured that a DNR order does not mean ‘no care’, but rather directs clinicians to allow a patient to die naturally in the event of a cardiac or respiratory arrest. This means that prolonged chest compressions and endotracheal intubation will be withheld, but not other critical interventions, including the treatment of pain and for the feeling of being short of breath (along with a host of other possible symptoms). In this way, physicians may help reduce the anxiety and shock that can accompany a code discussion during an admission to hospital.

While many family doctors and specialists are already doing this, numerous patients still present to hospital without a clear directive for their goals of care. Our lack of integrated electronic medical records across Ontario also means that even if family doctors have engaged in this discussion with their patient beforehand, the hospitalist physicians do not have access to it, and therefore must go through a full code discussion again. But so long as our patients continue to require detailed code discussions at each hospital admission, we should continue our attempts to balance the risks and benefits for all of our proposed treatments and talk to our patients about them, especially when they surround the issue of CPR in our patient’s final moments.

The comments section is closed.

Thank you for this article Kieran – it definitely sounds as if you are the type of physician I would want to encounter in the health system.

The diagram you provide could help many family grapple with this type of decision. I also believe that it would be useful to develop a standard family (or physician) guide for the actual discussion we all should have at some point (and this is likely sooner than many of us expect) .

In the case of my parents – we were extremely lucky to have a geriatric psychiatrist willing to lead a very sensitive and ultimately heart-warming discussion with my parents to establish a DNR code for them. I wish all families had the good fortune of this phenomenal health provider when faced with this type of discussion.