Canada is the only country in the world that provides universal public insurance for medical and hospital care but not for prescription drugs. Is this a desirable divide in health policy or a failing of our health care system? If the latter, what would our system ideally look like?

In an effort to answer this question based on evidence, values, and insights from real-world experience, I recently hosted a national symposium on the future of drug coverage in Canada: Pharmacare 2020. Participants represented a deliberately wide range of perspectives, including those of pharmaceutical companies, governments, health professions, academics, patient groups, health charities, pharmacies, private insurers, employers, and unions.

A working hypothesis behind the meeting was that most stakeholders would agree on most of the “big picture” issues in this important component of our health care system. And agree they did!

Because the conference was meant to foster productive dialogue on policy problems, goals, and solutions, we incorporated anonymous, real-time polling of delegates as a means of engaging participants in frank and honest discussion. The polling results illustrated remarkable (perhaps even inspiring!) agreement on key policy issues and some telling disagreement on others.

First and foremost, the jury is in on whether our system is broken. Over 90% of conference delegates said that pharmacare in Canada needs to be reformed. Speakers and delegates from all perspectives expressed shared concerns about the accessibility, appropriateness and cost of prescription drugs under our current system that fragments pharmaceutical policy from the rest of our health care system.

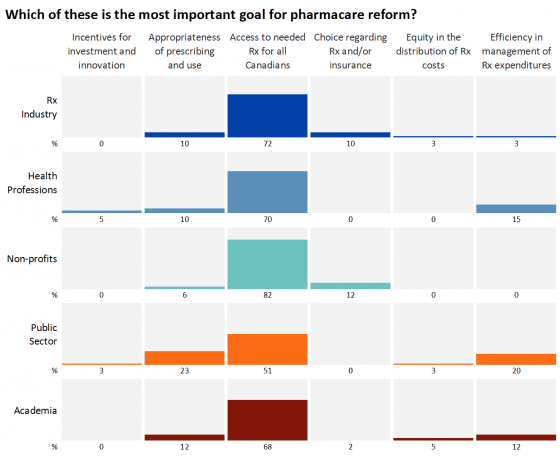

What was most surprising to me, however, was the degree of consensus on policy goals. Approximately two-thirds of conference delegates said that ensuring access to necessary prescription drugs for all Canadians was the number one goal for pharmacare reform. As shown in the slide of results by respondent type, ensuring access to necessary medicines for all Canadians was the top goal within all categories of conference delegates, including those from the pharmaceutical industry, health professions, non-profits (patient groups and health charities), government, and academia.

Why is consensus on an issue as obvious as promoting access to medicines so important? Because recent and older studies have found one in ten Canadians report skipping prescribed doses or not filling prescriptions altogether because of cost. Those studies have also shown that pharmacare systems with income-based deductibles – such as the one British Columbia has and the one Alberta proposed last week – result in the worst rate of access to medicines in Canada.

Even very small patient charges can prevent people from using medicines that can improve their health and save money elsewhere in the health care system. Thus, the #1 goal for pharmacare reform – access to necessary medicines – is best assured by a system that covers all Canadians for all of the costs of all necessary prescriptions. Moreover, such a system would also help to address other priority goals for reform, including improving prescribing appropriateness and more efficiently managing expenditures.

At the other end of the spectrum in terms of policy priorities, a majority of delegates, including a majority of those from the pharmaceutical industry, said that providing incentives for pharmaceutical investment and innovation is the least important goal for pharmacare reform. A sizable share of participants from most stakeholder groups said that ensuring choice regarding insurance and/or drugs covered is the least important goal for reform.

Though there is clear consensus on need for reform and on the most and least important goals for reform, financial interests did affect voting on specific policy options. Whereas less than a quarter of delegates from the pharmaceutical industry felt that a single-payer public pharmacare system was the right approach to patented and generic drug pricing, nearly two-thirds of all other delegates felt that such a system would be the right approach to those issues.

A significant majority of non-pharmaceutical industry delegates also said the ideal role for private insurance would be minimal in the future with drug coverage being provided through a comprehensive universal public pharmacare program. It was pointed out during the conference that a comprehensive, public pharmacare program was the original vision for medicare in Canada.

In 1964, the Hall Commission called on the federal government to provide 50% of the costs of universal provincial drug benefit programs that used a formulary managed by a committee of experts and kept patient co-payments at or below $1.00 (approximately $7.50 in today’s financial terms). Such a system is virtually identical to the system called for by the 1997 National Forum on Health, in part because such an approach to drug coverage exists in all other countries that offer universal insurance for medical and hospital care.

At the close of this recent conference on pharmacare in Canada, a majority of delegates said lack of political will was the leading top barrier to meaningful pharmacare reform. This is important because the next leading barrier to reform identified by delegates was opposition from interests.

Completing the medicare prescription – so that medicare does not end at the entrance to a pharmacy – will improve the health of Canadians while saving money. But it is in the “saving of money” that we run into problems. Every dollar of savings in the system is a dollar of someone’s income or profit. As there are billions of dollars to be saved (or lost, depending on perspective), some industries will launch intense public and back-room campaigns to oppose expanded pharmacare. This is why it is so important that ordinary Canadians and honest representatives of their interests get involved in this policy debate and call on governments to expand public pharmacare programs.

I’ve been studying pharmacare in Canada for 20 years. Never before has it been so clear that stakeholders across the spectrum believe reform is needed. This consensus, as well as the clear consensus on both the most and the least important goals for reform, must be kept in mind as the debate escalates. If policy makers can be held to account on performance of their systems against the most critical goals – ensuring access for all, improving appropriateness, and managing expenditures –meaningful and positive reform is possible by 2020.

The Pharmacare 2020 conference was part of an ongoing conversation about future of prescription drug coverage in Canada. We encourage people to visit our website now and in the future to find out more about the policy issue and options for reform.

The comments section is closed.

Especially important in expanding access is controlling cost. While there is broad-based support for pharmacare reform around access of needed drugs for all Canadians, I suspect the pharma/non-pharma divide will become readily apparent when we consider whether access to drugs should be appended with the qualifier “at any cost”. We should not confuse coverage with cost sustainability – drawing a parallel to expansion of coverage in the United States, the healthcare service providers (physicians groups, hospitals) were likely ecstatic about the idea that more individuals would be covered, as they would as long as SOMEONE was paying the exorbitant bill they were charging without scrutiny.

Evidence-based rewarding of the pharmaceutical industry through appropriate price regulation should be the key factor considered moving forward. The sanctity of life should not be pharma’s leverage to pressure governments into funding irrational drug prices owing to pharma’s insatiable focus on profits and the bottom line.

Thanks for igniting this debate. Pharma coverage in home care sector is a huge challenge – we need to move from conversation to action.