As part of the 2003 Health Accord, the Federal Government made major investments in interprofessional education. This included contributing $28 million dollars to build training centres across Canadian colleges and universities.

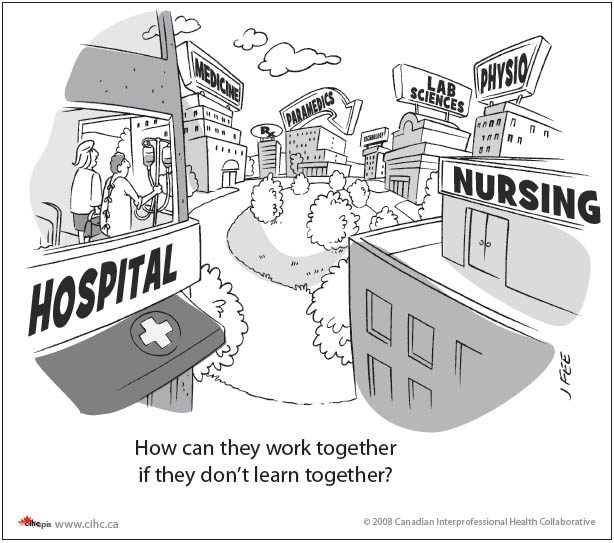

Investing in interprofessional education was motivated by the belief that changing the way health care professionals work together would be a key part of health system renewal. More interprofessional practice was envisioned as a way to achieve the goals of health system renewal set out by the Romanow Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada of improving patient centredness, safety and quality of care.

The first step to lead this change was teaching the next generation of health care professionals how to more effectively work together.

A decade after this federal investment was made alongside some provincial governments contributions, Healthy Debate asks whether this investment in education has translated into better interprofessional practice.

A ‘world class’ interprofessional education system

While it might seem straightforward that health care professionals will have the skills to work together on patient care, research has demonstrated that these skills need to be taught.

Just because people work near or with each other, does not mean that they are working interprofessionally.

Interprofessional education focuses on developing the skills needed for health care providers to work together in teams. It focuses on improving understanding of what various health professionals do, and how to effectively communicate and collaborate in patient care.

Louise Nasmith, Principal of the University of British Columbia College of Health Disciplines says that the federal investment made Canada a world leader in interprofessional education, with “every university in Canada with a medical school having an office of interprofessional education”.

Part of this investment took the form of 20 demonstration projects, funded through the Interprofessional Education for Collaborative Patient-Centred Practice (IECPCP). This totaled approximately $28 million dollars, according to Sandra MacDonald-Rencz, Executive Director of Health Canada’s Office of Nursing Policy.

These projects included developing curricula and practicum’s for interprofessional education across faculties of medicine, nursing and allied health. For example, a University of Manitoba demonstration project focused on interprofessional placements and learning in geriatric care. Another project led by Cancer Care Nova Scotia was a partnership with St. Francis Xavier University to develop 10 modules of interprofessional cancer care for their nursing students.

There were also unprecedented levels of research on interprofessional education. Canadian researchers dominated and advanced the study of interprofessional education during this time, in part due to evaluations of the demonstration projects and other federally-funded research in this area.

The demonstration projects through IECPCP have all wrapped up. With no further federal dollars for interprofessional education, universities and in some cases provincial governments, have stepped in to keep the interprofessional education curriculum and programs built with these dollars going.

Interprofessional education seems to be here stay. Accreditation bodies are now including standards of interprofessional education as part of the curriculum across schools of medicine, nursing and other allied health professions (such as physiotherapy and pharmacy).

Questions remain though on how Canada’s interprofessional education structure will change behavior of health care professionals in practice.

While there have been many studies which evaluate the short-term outcomes of education programs, such as student attitudes towards other professionals, there is a lack of strong evidence on the relationship between interprofessional education and practice.

Scott Reeves, a professor at the University of California San Francisco and editor of the Journal of Interprofessional Care notes “there is a dissonance between what is taught and practice, with cultural and organizational issues impacting collaborative practice.”

“A lot of rhetoric” and “lip service” for interprofessional practice

In spite of Canada leading on interprofessional education, interprofessional practice is far from a reality in most health care settings.

Nasmith says that students going into practice find “lip service” paid to interprofessional practice. She says it is not yet “embedded into the organizational fabric of how business is done through professional development and continuing education.”

MacDonald-Rencz acknowledges that federal funding for interprofessional education spanned about 10 years, and that “to really get practice changes, you need an investment of 20 to 25 years… unfortunately priorities do change.”

Learning to work together is cultural. Reeves suggests that while “there is a lot of rhetoric about team work, a lot of practitioners do not know what a good interprofessional team is.” He stresses the need for health care workplaces to include interprofessional education as part of ongoing professional development.

Nasmith says “there hasn’t been an investment in the system in allowing people to work collaboratively.” In order to really bring concepts of interprofessional education into practice, health authorities, hospitals and other provider organizations need to partner with universities and use their resources to help translate the ideals taught to students into practice.

Some provinces, such as Alberta and Ontario have moved ahead with province-wide strategies for interprofessional education and practice.

Ontario’s Blueprint for Action

Ontario has been identified as a leader in interprofessional practice. The provinces’ 2007 Blueprint for Action saw the development of core competencies for interprofessional care and resources to help translate the ideals of collaboration and teamwork into clinical practice.

An example of bridging education and practice has been the SCRIPT (Structuring Communication Relationships for Interprofessional Teamwork) program, based at the University of Toronto Centre for Interprofessional Education. This program developed clinical teaching units and curriculum for interprofessional education in general internal medicine, rehabilitation and primary care.

Maria Tassone, director of the Centre for Interprofessional Education, noted that the curriculum was based on “an intentional partnership between education and practice environment.” Tassone says “government set the tone for collaborating” by offering financial incentives for interprofessional education programs that were partnerships between academic and practice settings.

Alberta Collaborative Practice and Education Framework for Change

Alberta has more recently embraced a provincial strategy for interprofessional care. The Collaborative Practice and Education Framework for Change, was launched in fall 2012 and brought together various stakeholders, including professional groups, universities, employment associations and government to develop a framework for interprofessional practice. Doing this across Alberta was motivated by the belief that “large scale system change toward a norm of collaborative practice in health care delivery requires that future efforts be co-ordinated in an integrated, strategic approach.”

However, funding tied to specific interprofessional practice programs has yet to emerge from the Framework.

Doug Myhre, Associate Dean of Distributed Learning and Rural Initiatives at University of Calgary’s Faculty of Medicine notes that “there is no money attached to this, it’s just a statement.” Myhre says while “everyone believes this is the right thing to do, no one is putting money into it.”

While there may not be specific projects linked to the framework, some practice models in Alberta, such as the Primary Care Networks, which are led by family doctors, working with other health professionals like nurses and pharmacists, do promote interprofessional practice.

Nevertheless, Myhre argues that “the PCN’s didn’t entrench education into their mandate.” There are concerns that in the absence of formalized ongoing professional education, it is difficult to change professional culture and improve collaboration in practice.

Maintaining momentum for interprofessional practice

While Canada has been identified as a leader in interprofessional education and research, translating this into practice remains a challenge.

Ivy Oandasan, a family doctor and researcher who developed the framework around funding the 20 federal demonstration projects, describes the material developed from federal demonstration projects as “good work, lost in a drawer.”

She suggested that while universities continued to support interprofessional education after federal funding for interprofessional education dried up, many health care provider organizations and governments have moved on to other priorities and haven’t provided the supports necessary to change practice – ongoing education and partnerships.

There has been a great deal of high quality curriculum development, trainees and research in interprofessional education generated in the past decade. Now, it seems up to provinces, health authorities and provider organizations to support interprofessional learning as part of professional development, to help bring these ideals into practice. As Louise Nasmith says “its not going to happen because you throw people together.”

The comments section is closed.

The team practice idea used to work well in rheumatology if you were lucky enough to see the right doctor. When I was diagnosed 30 years ago I was admitted to the hospital for a few days because of the drug I was prescribed. The time in hospital was treated as an education session as well.

I met and was treated by a physiotherapist, occupational therapist and referred to an orthotist. That was excellent as a way to learn the best ways to deal that type of chronic illness. Those days are long gone.

Could electronic health records help? In theory it will be easier to doctors to exchange information with EMR and also for patients to have access to it.

%featured%With the current popularity of the idea of self management maybe patients can become the captains of the team at least when it comes to allied health care professionals. Of course for that you need health literate and informed patients and I hear those people are not in the majority.%featured%

There are no barriers in Canada to choosing your own specialist doctors. The hard part is finding out who the best doctors are. I like to be referred to doctors who are associated with teaching hospitals, are not too close to retirement, and who publish now or in the past. Then I ask my GP to refer to those doctors.

I think the current IPE initiatives are looking at better ways of training medical professionals. I also am a member af the Health Mentor program, as well as being involved in Patient Partners where the team approach does come up in demonstrations. In addition i am using alternate methods of sharing knowledge with other patients. A doctor can be the team leader but too many have other priorities or too few patients with a particular problem to be aware of all of the possibilities.

I am overall skeptical of this “Team practice” concept. The issue I have is that a team must have a leader. Classically that leader was the physician, and that physician would bear the responsibility of all decisions and actions made by the team. Now, it seems that there is either no leader, too many leaders (we are all leaders! Hurrah!) or absentee leaders like hospital administrators. This, in my opinion, damages patient care and contributes to worse care, worse continuity of care, and a lowering of public trust in physicians.

Furthermore, interprofessional education, that being knowing the roles of each person involved in the care of the patient, is a laudable goal. But realistically, most doctors don’t even know what other doctors do. Ask a family doctor what a pathologist really does, and they’ll answer autopsies. Ask a surgeon what a psychiatrist does, and they’ll answer nothing.

Finally, in my experience as a medical student and resident years ago, interprofessional educational sessions came across not as learning experiences or collegial team exercises but as dog-and-pony shows reminding future physicians that “hey! We’re important too!(and will soon be taking over your job!”)

It’s disappointing that a promising approach to restructuring educational culture and medical practice has been paid lip service and only a paltry sum of money allocated over the last decade.

As a Patient/Client member of the University of Toronto Centre for Interprofessional Education’s Health Mentor program, I can testify how patients experience interprofessional care:

– the patient finally feels part of the care team

– hierarchical power struggles among HCP’s disappear

– practice is a true example of patient centred care

– patients better appreciate the interrelationship of their HCP’s

– results are increased engagement in treatment

– Patient feels “listened to” leading to better communications

Can interprofessional care lead to improved health outcomes? Even for patients like myself who have lived for over 30 years with a chronic illness, participating in an interprofessional program was a refreshing, eye opening experience. It’s different from a lifetime of seeing specialists. It’s different from a multi-disciplinary approach. And having patients play a role in the education of first year health professionals is a fulfilling and empowering experience for both patients and students.

Along with a few other Health Mentors I blogged about our experience participating in the program. You can connect to all of our reflections here http://patientcommando.com/stories/health-mentor-season-one-episode-1-zal/ .

A bedrock principle of interprofessional care from the patient perspective is better communications and the evidence is there that improved health outcomes are the result.

When our government can blow $1 Billion on a weekend G8/G20 meeting but only allocate $28 million over a decade to a promising change to health care practice that could save our system many billions, patients can understandably wonder whether certain healthcare stakeholders and policy makers are more interested in protecting existing power structures than improving health outcomes.

Bringing the patient experience into your discussion adds the capacity to challenge these entrenched positions and enrich the meaning and potential of interprofessional care.

%featured%Like so many things, a build it and they will come, “educating inter-professional students together to promote work practice teams” has seemed at times questionable and yet, there is evidence that team practice is desired by both patients and many doctors so it only follows that they should find themselves better off learning, sharing and working together.%featured% It’s long been known that the medical profession [not all doctors], wanted control over every aspect of what a patient could do or not do and so this group could see no benefit to working with others for the good of the patient. This has proven to be futile and anyone today, patient or professional now recognizes that mission was doomed. The younger generation of doctor seems very interested in talking to patients as well as learning from other professionals. I am most encouraged by those I’ve met and interact with and can see the pattern is changing which offers hope for the future. Creating interdisciplinary professional education models is not only better, eventually it will be the only model available for students entering the health sciences.

Elizabeth Rankin BScN

Still not sure if Canada is still ‘experimenting’ with oris actually committed to interprofessional training in support of interprofessional practice such as in primary health care. %featured%One would have expected much more progress but scant evidence that front line care is changing/evolving as our research is showing. Perhaps another 10 years and we’ll know the answer.%featured%