Prescription drugs provide important benefits to patients, and are an essential component of the health care system. They also have significant costs: Canadians spent roughly $35 billion on drugs in 2013, or about 16% of total health care spending.

Drug costs have put significant strain on provincial budgets. In response, most of Canada’s provinces and territories have joined together to form the Pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance (PCPA), with the goal of negotiating better prices on both brand name and generic prescription drugs.

Payments for prescription drugs in Canada

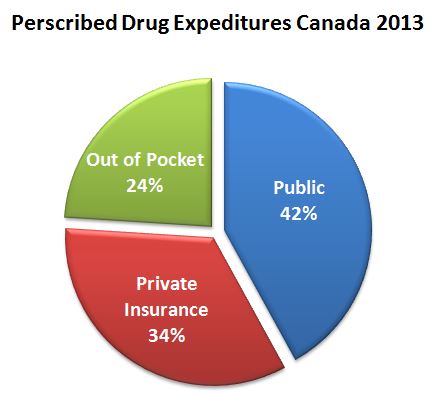

In Canada, the majority of prescription drugs consumed outside of hospitals are paid for either out-of-pocket by individuals or by private insurers, with 26% to 45% of prescription drug expenditures covered by public drug plans administered by the provinces and territories. Individuals covered by these public plans typically include seniors, people with disabilities, those on social assistance, people receiving home care, and those residing in long term care facilities. Many provinces also provide some form of catastrophic drug coverage.

Because public drug plan costs are a major component of provincial health care spending, governments have increasingly been negotiating product listing agreements with drug manufacturers, which typically provide discounts on the price of prescription drugs, often connected to the volume of drugs purchased.

Marc-André Gagnon, Assistant Professor at Carleton University says, “Drug companies arrive with artificial inflated prices and from there, negotiation takes place with the main purchasers in terms of their bargaining capacity.”

Recently, Canadian provinces and territories have negotiated drug prices in isolation, but because a province’s bargaining power is tied to its size, the result has been uneven deals across the country. Smaller provinces were often paying more than larger provinces for the same drug, says Steve Morgan, Director of Centre for Health Services and Policy Research & Professor at the University of British Columbia.

The Pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance

In 2010, the Pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance (PCPA) was formed under the Council of the Federation to join provinces and territories to negotiate prices for publicly covered drugs. The PCPA examines all drugs recommended for funding by the Common Drug Review and the Pan-Canadian Oncology Drug Review and then decides whether joint Pan-Canadian negotiations for the drug should occur.

If the PCPA decides to move forward on a specific drug, one province will assume the lead and begin negotiations with the drug manufacturer. The specific negotiation process varies by province. In Ontario, all negotiations are managed through the province’s Senior Pharmacist.

If an agreement is reached, the lead province will sign a Letter of Intent with the manufacturer, which is shared with the other provinces and territories in the PCPA. Once these negotiations have concluded, each participating province and territory makes their own final decision on whether to fund the drug and enter into their own product listing agreement (based on the Letter of Intent) with the manufacturer.

PCPA negotiations for brand name drugs are currently being led by Ontario, with Nova Scotia and Saskatchewan taking the lead on generics. David Jensen, spokesperson for the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care, says “Working together improves our buying power and allows for better utilization of resources within the Health Ministries.”

“It has been a major accomplishment to successfully collaborate with 10 jurisdictions on complex drug files,” Jensen says. As of September, there have been 48 negotiations, and nine are currently underway. The PCPA decided not to negotiate 16 drugs due to the lack of evidence around their effectiveness.

The PCPA has estimated that joint negotiations for 43 brand name and 10 generic drugs have already saved a combined $260 million in drug costs annually.

According to a 2013 study in BMC Health Services Research, policy makers have stated that the joint collaboration has the ability to enhance equity in access and drug prices across provinces. This is because small provinces have less bargaining power due to their small population size, but by combining forces with larger provinces like Ontario, they have been able to get much better prices than they could their own. As a result, it is hoped that these smaller provinces will be able to cover drugs they previously could not afford.

Challenges with joint negotiations

The PCPA has faced several challenges. The negotiating power of the initiative is less than it could be, because provinces are not required to be involved, and Quebec (Canada’s second most populous province) has declined to participate.

In addition, manufacturers have generally been unhappy with the process, according to a report on the PCPA prepared by IBM. Manufactures have reportedly pointed to a lack of consistency among provincial leads and a lack of transparency around timelines, PCPC process, and the specific criteria on which a product is evaluated. Manufacturers have also reported a sense that the provincial negotiation leads lack the authority to truly negotiate, because individual provinces retain the right to not cover their drugs, even after a price has been agreed upon through a Letter of Intent.

Cooperation has been another key challenge. Joel Lexchin, a professor at York University and emergency physician at the University Health Network, says “[The PCPA] is promising but it’s limiting because it requires a degree of cooperation amongst plans.” Cooperation has been a challenge at times due to a process that many stakeholders feel is too informal, according to the IBM report. A more “transparent process with some additional clarity around average timelines for each stage would be helpful to keep stakeholders, particularly manufacturers, informed about the status of negotiations,” the report reads.

“There is a need for a more formal and consistent process, increased transparency and dedicated resources,” agrees Jensen. He hopes that the new PCPA office announced by the health ministers will address some of these issues. However, details on the new office are scarce, and the PCPA website indicates only that “implementation plans and timelines are currently being finalized.”

Consequences for cost-effectiveness research

While joint negotiations can improve the prices provinces pay for brand-name medications, these negotiations may have unintended consequences.

When a province or country negotiates with a drug company, the details of the final agreement remain secret (though Germany is considering ending this practice). For example, while it is public knowledge that the Pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance has negotiated a discount on the Cystic Fibrosis drug Kalydeco (list price: $300,000 per year), the exact amount of this discount is a secret.

These secret discounts allow provinces to cover drugs they otherwise could not afford, but they also make it very difficult to accurately assess the cost effectiveness of other drugs.

Currently, new drugs approved for sale in Canada are evaluated by the Common Drug Review to determine whether they are cost-effective, and thus whether they should be covered by provincial drug plans.

But problems arise when the real cost of drugs are kept secret, because the cost effectiveness of a new drug is judged in comparison with other drugs that are already on the market. If the amount being paid for the comparator drugs is not known because it is secret, it is essentially impossible to do a valid cost-effectiveness analysis of a new drug. “It introduces a lot of uncertainty into the process,” says Ahmed Bayoumi, a scientist at the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute of St. Michael’s Hospital who sits on the Common Drug Review’s Canadian Drug Expert Committee.

Patient concerns

Gail Attara, chair of the patient advocacy group Best Medicines Coalition, claims that the PCPA offers more value to governments than patients. She worries that “bureaucrats” will make decisions about which drugs to fund based exclusively on the cost, and overlook more expensive drugs that some patients need.

In particular, Attara is concerned that if the increased purchasing power of the PCPA results in deep discounts on certain drugs within a therapeutic class, provincial plans may stop paying for other drugs in the class and force patients onto the cheaper drugs. This practice is known alternately as reference drug pricing and therapeutic substitution. British Columbia and Quebec have both experimented with variations of this approach.

There is some debate as to the effectiveness and safety of therapeutic substitution, though the preponderance of scientific evidence indicates the practice is safe and produces cost savings.

Another concern raised by patient groups in the IBM report is that while patient groups have the opportunity to provide input to the Common Drug Review, they do not currently have a “seat at the table” for PCPA negotiations.

Gaps in the system

Although provinces have joined in a bid to increase their purchasing power, these negotiations are not helping all Canadians. As Morgan notes, “provinces are getting a deal on their proportion of the spending, but people without public insurance [still] have to pay artificially inflated prices.” He adds that those who must pay for drugs out-of-pocket “are vulnerable folks who have no purchasing power.”

The numbers are not insignificant. Roughly a quarter of Canadians do not have any drug coverage at all, and over half are covered by private drug plans.

Gagnon argues that the savings achieved by the PCPA ought to be beneficial to everyone. “PCPA is a very important step in the right direction… we have to just make sure that it’s sufficient and benefits everybody,” he says. Gagnon believes that the PCPA should not be viewed as an end-state, but as a first step towards a sustainable approach to universal pharmacare.

While the PCPA will almost certainly result in better deals on new drugs for public drug plans, it remains to be seen whether it will open the door to a provincially led minimum standard of public coverage for pharmaceuticals in Canada.

The comments section is closed.

January 30, 2018: The pCPA and CGPA just came to an agreement to reduce costs for generic drugs. On the surface it sounds great. From what I understand from the above comments and what I have learned from personal experience as a physician over the last 36 years I have grave doubts. pCPA and CGPA negotiations are touted as collaborative. That could not be further from the truth. Collaboration requires all stakeholders to commit to a common goal. As long as business ethics compete with medical ethics nothing but patchwork solutions will be possible. The real challenge is convincing the entire world of this reality so that meaningful solutions can be crafted on the back of a truly universal common goal. Nothing has changed – only appearances. It is time for a knight-move. I assume my comments will be taken as idealist and unrealistic – even crazy. Regardless, I am proud of them and I believe I am only saying what others are thinking.

We must be careful not to drop the prices of generic drugs too much. Smaller Generic Manufacturers will not be able to compete against the big established companies. Overall, manufacturing costs will be going up worldwide and unless you buy in massive bulk, your costs are substantial. In the end, the small companies drop out of the picture or get bought out, and the big fish once again monopolizes the industry. Along with that , comes huge profit margins for “big pharma”.

Good resolution. One of the iesuss that should be addressed is the limited ability of elderly people in long term care to be transferred from one province to another province where their family is. I personally know two families whose mother was in long term care, and when employment took the family to another province the elderly parent could not be transferred into the long term care system of other province. In both cases this resulted in a situation where the son flew back to the other province once every month to visit his mother. This was emotionally extremely difficult for the mother in long term care. In both cases there was no other family to visit her and care for her. I am not certain of the details of provincial health care regulations that may or may not allow people in long term care to be transferred between provinces; but inter-provincial agreements should allow people to be transferred to be with family.

Drug prices are higher and I see most of the people getting generics to lower their healthcare costs. Most of the people get medications online. Even I too get medications online at discount price and save money. I get them online at InternationalDrugMart. This is the place where I saved on medications.

Meanwhile the province of Ontario is backtracking on its own cap for generic prices, depending on how many manufacturers there are of that particular drug. For a sole source manufacturer they will be able to charge 75% of the brand price, which is outrageous. Canada already pays among the highest prices in the world for generics. Instead of arbitrary caps, it makes more sense to have a universal pharmacare program that negotiates the best price for these drugs.

The PCPA is farcical and seriously undermines why any innovator should engage with Canada to invest in the research-based knowledge economy. The PCPA inhibits this incentive to innovate through arbitrary price discounting.

The deal is to undertake the expensive and risky act of developing new medications to gain a patent allowing innovators to recoup the expense of R&D, and incentivize this pursuit through this temporary grant of exclusivity. If innovators cannot capitalize on this transaction – who will develop the medications we need in the future? Do we not need these new medications? I think the recent outbreak of Ebola, annual flu risk, and challenges with ageing population should inform you that we absolutely do – Marc Gagnon – take note!

Some perversities of this mechanism is illustrated as follows: if CADTH gives a straight ‘list’ recommendation – where medications have been deemed cost-effective – PCPA still want a further reduction in price. This obviously undermines the CADTH recommendation and arbitrarily penalises the innovator. As a tax-payer – if PCPA simply ignores these recommendations – why should I pay for this additional administration in CADTH? Also, if a second indication appears for a drug – the PCPA wants a further reduction in price? Hasn’t more value been demonstrated to patients here?

Additionally, each of the nine participating provinces in PCPA have different qualification for pubic coverage – some only cover people over 65, some have a degree of universality – so regardless of the size of each province, the level of coverage varies widely – why is it then fair that all provinces receive the same price through this negotiation? Haven’t thought it through have you boys?

Until Canada can demonstrate or legislate true healthcare equity for each individual between provinces, the PCPA will remain a farcical temporary fix. As for Canada’s innovation agenda – policies like the PCPA, overtly aggressive towards any stakeholder with any intention of trying to innovate; this position will forever condemn Canada to the economic ‘Dutch disease’. You sure you want to go long in the economy based on oil sands?

This is a great praecis on the PCPA. We’ve recently done a thorough look at the evolution of PCPA with some suggestions as to how economics might be better incorporated into price setting as well as some of the legal issues that could arise – the article is now in press and is scheduled for print in Value in Health this December – http://t.co/ZkqPmKXVHd .

While the PCPA may achieve some equalization in prices, it’s not at all clear how it would enhance equity. Although there is wide variation between provincial drug programs in terms of approved drugs, these plans mainly benefit seniors and persons on social assistance. Most Canadians require private insurance to pay for drugs, and often experience heavy co-payments and deductibles. Approximately 15% of Canadians have no insurance at all and must pay the entire cost out of pocket. These groups will continue to face high drug prices and do not benefit from the PCPA. It would be good to see national initiatives take on the challenge of enabling access to needed medications for the most vulnerable members of society.

I’m sorry but as a healthcare professional working in this system i think people need to wake up and stop patting the bureaucrats on the back for coming up with this strategy. In fact, I think this focus on drug pricing is archaic. Have we not learned from experience that theses strategies bring only short term gains.

No where is there mention of the drug shortages that have cost the lives of many patients and increased the suffering of others. We are into year six of this epidemic which is aggravated by this pre-occupation on drug pricing. As a result, where there was competition amongst generic manufacturers there is less and less as more molecules become single source again (a single supplier for the Canadian market). Where is the savings? What about the delay in the provinical approval process when a new generic comes to market? Canadians see the loss in savings when a generic drug is approved by HPB for the Canadian market because every pronice is allowed to go through their own process of generic drug approval. That means the new generic equivalent is delayed by not days but usually months and in the case of omeprazole (generic Losec) the delay was a year in provinces like Alberta.

The comment that patients are not receiving the benefits of the savings is correct. Especially when agreeemnts are struck with brand as well as generic manufacturers for rebates that are paid to provincial governments, not to patients. Where do those rebates go? Certainly not accounted for in any open accounting that the public has access to? If they are going into general revenues, those revenues could be used for anything, which means they are not directed to reduce healthcare costs or to improve access to diagnostics or, as pointed out, to lower drug costs for all Canadian patients including those without drug plans.

I’m sorry, but this preoccupation with drug cost is so mickey mouse, that I’m embarrassed for those who take credit for the strategy as a benefit for Canadians. Again, it is bureaucrats who are making decisions that affect Canadians, patting themselves on the back for ‘job well done’ and enjoying the benefits of their job well done via promotion or bonuses and/or pensions that we in the private sector can only dream of.

Drugs are a tool, and like any other tool are only of value when they are used intelligently. Focus on how, when and how often these tools are used. Empower those professionals who are in a position to make more effective changes to the way these therapeutic tools are used. That will not only reduce drug expenditures where it makes sense, but will improve health outcomes and the overall quality of healthcare.

After all, isn’t that what we should be working towards?

Excellent point Jeff. We are all patients and most patients are both taxpayers and voters. Government is the mechanism by which we do things together. Buying into the ‘patients vs. government’ agenda helps companies pressure governments to pay over the odds for health technologies at the expense of other patients who dont have a company or a patient advocacy group lobbying for them.

These initiatives are to be encouraged. Canadian Blood Services for over 10 years has been purchasing blood products for all provinces except Quebec. There is generally one supplier but a significant competition occurs at the time of the RFP. There is consultation with the users. They have successfully lowered the cost of these pharmaceuticals. All provinces are charged back by CBS the one negotiated price. The PCPA initiative can learn from CBS’s experiences.

I always find it interesting that advocates so often view governments as having such wildly different agendas than their (the advocates’) constituents. In the article above, Ms. Attara, Chair of Best Medicines Coalition suggests “the PCPA offers more value to governments than patients.” Aren’t patients taxpayers too? Aren’t we all taxpayers? Shouldn’t we want our governments to pursue value as they allocate our tax dollars to our social programs?