Health care has supposedly entered an era of patient involvement, where important medical decisions are shared between doctors and patients. But many believe that the reality in Canadian health care falls well short of this ideal.

Complex medical decisions can prove difficult for patients, who are often faced with dizzying amounts of information about benefits and risks, frequently presented in inaccessible, academic formats. At other times, they don’t feel they get as much information as they want. This leaves many patients feeling that they are less informed about their options than they would like, and are not able to fully participate in decisions about their own care.

In response, decision aids have been developed to enhance patient engagement by providing complete and accurate information to patients in formats that can be easily understood.

Patient decision aids have existed for more than two decades and there is good-quality evidence that they help patients make more informed decisions about their care. Why hasn’t this proven, patient-centred intervention caught on, and what would it take to make that happen?

Informed decision making?

Effective communication is at the heart of informed decision making, explains Wendy Levinson, a scientist at St. Michael’s Hospital. The trouble is that too often, communication isn’t as effective as it should be.

For example, research shows that even after being counseled by their doctor, patients frequently have unreasonable perceptions of probabilities of surgical benefits and harms, and lack awareness about alternative options.

Levinson believes this is due to ineffective communication born of too much medical jargon and one-sided conversations between doctors and patients.

Decision aids

Patient decision aids are meant to address the challenges of shared decision making by presenting patients with information that is easy to understand and answers the questions that are important to them.

They are designed to be used when patients are faced with more than one reasonable treatment option, when no one option has a clear advantage over others, and when each option has potential benefits and harms that patients may value differently.

Decision aids come in a number of forms, such as videos, web based tools, and interactive computer programs. They use plain-language, and often employ visual diagrams to illustrate concepts.

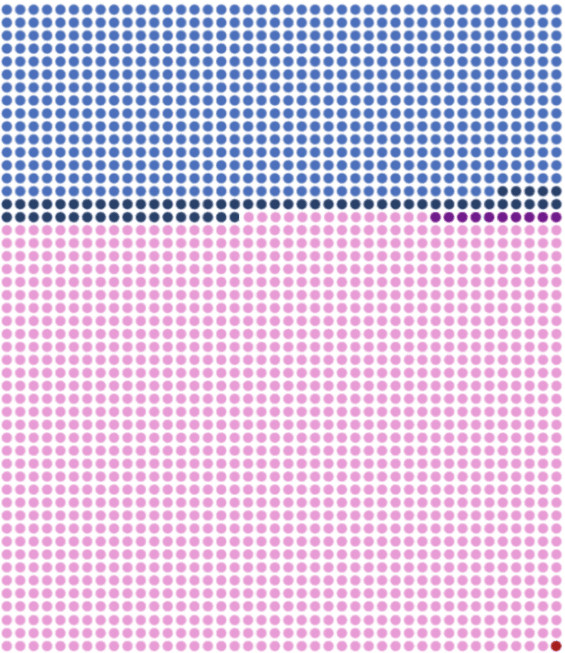

To illustrate, the following is an excerpt of a decision aid prepared by the Canadian Task Force on Preventable Health Care to help women aged 40-49 years understand the risks and benefits of mammography:

In this graphic, each dot represents 1 woman (○ = 1 woman). Pink dots are women who received a negative test result, light blue dots represent women who received a false positive and required further imaging, navy blue dots represent women who have a biopsy to confirm they do not have cancer, and purple dots represent women who have part of or all of their breast removed unnecessarily. The red dot represents the woman who would escape death from breast cancer.

Decision aids describe all the options available, as well as the possible benefits and harms associated with each option. To help with this, some decision aids include examples of other patients’ experiences with different options. The goal is to help patients consider their options from a personal point of view, so that they can reflect on how important different benefits and risks are to them, explains Dawn Stacey, Director of the Patient Decision Aids Research Group at the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. .

This helps patients develop realistic expectations about the benefits of medical procedures. For example, while a patient might expect that a knee replacement will be completely effective in relieving their knee pain, evidence indicates that it is not completely effective for everyone. Knowing that there is a possibility that a medical treatment may not be effective can help patients be prepared in the event that a procedure does not provide an intended benefit.

Importantly, decision aids are meant to supplement traditional counseling by health providers, rather than replace it, with the ultimate goal of helping patients participate more actively in decision making in partnership with their health care providers.

Evidence for decision aids

Evidence indicates that decision aids are very helpful to patients.

According to a recent Cochrane review of 115 studies, decision aids increased patient knowledge about options, and patients who used decision aids also felt more informed and clearer about the information that mattered most to them.

There is also some evidence that decision aids help patients be more active in the decision making process, have more accurate expectations of the possible benefits and harms of each option and also that they help patients make decisions that are consistent with their values.

Interestingly, a systematic review of decision aids for surgical decisions also shows that when patients are fully informed about potential harms and benefits of all treatment options, they tend to opt for more conservative treatment. For example, compared to usual care (counseling without a decision aid), seven trials showed that fewer patients chose major elective surgery when exposed to decision aids. In one study from the United States, decision aids reduced elective knee replacement by 38% and hip replacement surgery by 26% in a 180 day period.

While Stacey emphasizes that the goal of decision aids is to inform patients, the use of decision aids can be associated with cost savings. Because patients exposed to decision aids more often opt for conservative treatment, decision aids have been associated with a 12-21% decrease in the cost of care.

Barriers to their use

Despite the evidence for the effectiveness of decision aids, they have not been widely adopted. Michael J. Barry, president of the Informed Medical Decisions Foundation, has said that “given the level of evidence, [decision aids] may be one of the best-documented but underused interventions in American medicine.” There is wide agreement among experts that the same is true in Canada.

One of the challenges to implementing decision aids is effectively integrating them into the process of care. Many doctors’ offices are not equipped with extra rooms for viewing videos, or space for computers for patients to use interactive tools. In addition, someone needs to distribute and administer decision aids, which adds costs for clinics.

While online tools can help mitigate these challenges, patient characteristics can also limit the use of decision aids. For example, some disadvantaged patients may have challenges accessing online tools, while written decision aids may be of minimal use for patients with limited literacy or whose primary language is not supported by the decision aid. While translations of some decision aids have been made, decision aids are not currently available in every language spoken in Canada.

Some doctors are also unaware about existing decision aids for a specific clinical decision.

Decision aids can also be costly to produce, notes Levinson. This is especially true of videos and web-based tools. And once produced, they need frequent updating as new evidence and treatment options arise.

But most experts agree that the implementation and cost challenges are manageable. The biggest barrier to more widespread use of decision aids is rooted in the culture of medicine.

Many doctors believe they don’t need decision aids. According to Stacey, many doctors feel that they already counsel their patients about benefits and risks, and so they do not believe decision aids add any value for their patients.

But Levinson argues that “doctors are not as good at communicating with patients as they think they are.” For example, Levinson’s research team taped conversations between vascular surgeons and patients, and found that surgeons spend lots of time talking to patients about the technical aspects of their surgery, but they spend much less time talking to their patients about their other options and the risks of the surgery. “Even for fairly major surgeries you’d be surprised how perfunctory the conversations were,” she says.

Decision aids in other jurisdictions

Some jurisdictions have taken action to in increase the use of patient decision aids.

In 2007, the State of Washington signed legislation that required the use of decision aids for all elective surgeries, and became the first jurisdiction to offer incentive in the form of greater legal protection to doctors who implemented decision aids in their practice. Maine and Vermont have also passed similar legislation, while other states such as Oregon and Minnesota are considering it.

Here in Canada, Saskatchewan has begun to actively implement decision aids for some elective procedures – knee replacement, prostate cancer and pelvic floor dysfunction – through its Clinical Care Pathways. Saskatchewan has largely used decision aids developed by the Ottawa’s Patient Decision Aids Research Group.

This is part of a wider effort to encourage shared decision making in Saskatchewan. “One of the things that really came out of the Patient First Review in 2009 was that patients wanted to be more involved in their care, and decision aids were seen as a way to help,” says Saskatchewan Ministry of Health’s Lori Latta, who has helped implement decision aids there.

The early results are promising. According to Latta, an evaluation of the Saskatchewan program showed that patients who have received a decision aid show much better understanding of the risks and benefits of their options than those who received only traditional counseling. In keeping with the research to date, about 30% fewer patients who had been counseled with a decision aid chose to have a knee replacement compared with those who received traditional counseling.

Enforcing standards for decision aids

One of the lingering challenges for the use of patient decision aids to enhance shared decision making is the need for clear and effective standards. Technically any organization – medical associations, academics, governments, arms-length bodies, etc. – are free to create decision aids. But there is no guarantee that these aids will meet the same quality standards, and there is always a risk that an organization’s bias might creep into a tool.

In the United States, lack of certification for patient decision aids has been cited as one of the greatest barriers to wider implementation. While the International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration has created a checklist for agreed-upon standards for high-quality decision aids, there is currently no body in either the US or Canada responsible for certifying that decision aids adhere to this checklist.

While the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute maintains an inventory of decision aids with a completed IPDAS checklist assessment on its website, until some sort of certification process is put in place, no one is accountable to ensure that decision aids are accurate, comprehensive, unbiased, and up-to-date.

The comments section is closed.

%featured%As a caregiver, myself, I think that Decision aids is vital to both the patients and the medical staff. One needs to be mindful, though, that the patient fully understands what the “aids” mean and what is being requested or talked about.%featured% As a physiotherapist, when I am dealing with a client, I explain in great detail various treatment choices, making sure they understand fully, before commencing treatment. The client feels then that they have had major input into what their treatment plan will be. It is about time that Doctors take the same steps when dealing with treatments of their patients.

Great article!

I am definitely one of those physicians who is under educated about decision aids, specifically where to find them. Does a central repository exist for these evidence-based tools? If so, can the authors please provide a link?

Hi Kieran – here you go: https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/AZlist.html

Hi Kieran

I’ve been trying to collect some on my site too, http://www.lessismoremedicine.com/hands-on

Please let me know if there are things missing that you’d like to see added.

Thanks a lot for an excellent update on patient decision aids and for raising their profile. Decisions aids are effective in fostering engagement of patients so they can share decisions with their healthcare providers. However, let’s not forget about the need to train these providers so they can promote their use with patients. Shared decision making is a process closely aligned with the use of patient decision aids but still , shared decision making does not equate decision aids: Shared Decision-Making: Easy to Evoke, Challenging to Implement. Kuppermann M, Sawaya GF. JAMA Intern Med. 2014 Dec 1. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4606. and Patchy ‘coherence’: using normalization process theory to evaluate a multi-faceted shared decision making implementation program (MAGIC). Lloyd A, Joseph-Williams N, Edwards A, Rix A, Elwyn G. Implement Sci. 2013 Sep 5;8:102. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-102. Therefore, more is needed to ensure that patients, all patients, have access and are encouraged in using decision aids. Healthcare providers definitively have an important role and training programs are needed.