Access to prescription drugs in Canada is not equitable. Drugs are paid for (i.e. reimbursed) through a complex system of methods which vary in terms of treatment options and out-of-pocket cost burden. The three main methods of reimbursement are government drug programs, private insurance (provided by an employer), and out-of-pocket payments by patients for all or part of a prescription. These can also differ among provinces or by private insurer benefits, which can create a postal code lottery for patients.

Universal pharmacare is meant to solve this problem and promises to make access to drugs fairer.

There are a few ways of approaching universal pharmacare. Prominent academics have published a vision for a national, comprehensive, single-payer system that provides access to drugs on a specific list (a formulary) at no out-of-pocket cost to patients. This vision has recently gained momentum with the publication of a report by the federal Standing Committee on Health (HESA), which sought to describe the benefits of universal pharmacare. The vice-chair of HESA, MP Don Davies, summarized the case for pharmacare: “The bottom line is that we can cover every single Canadian’s medicine needs and save billions of dollars every year. That’s better for everyone.”

On the face of the HESA report, universal pharmacare seems like a no-brainer. But there is a lack of a dissenting opinion surrounding the economics of universal pharmacare, with most people appearing to accept that the cost savings are a foregone conclusion. But shouldn’t offering coverage to more Canadians result in more costs, as was the case in Quebec in the 1990s, when they instituted mandatory drug coverage? To understand how the HESA report arrived at its conclusions, I took a look at their underlying economic evaluation published in a report by the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO).

The PBO report concluded that universal pharmacare would result in increased drug use for two reasons: More Canadians who are currently uninsured or underinsured will be able to access drugs and lower out-of-pocket costs (e.g. lower co-pays) may lead to increased consumption for those currently insured (for example, stocking up on EpiPens). Most would agree that increased access to beneficial drugs is a good thing as long as the costs are not prohibitive.

Despite this increase in drug use, the PBO report estimated that universal pharmacare will lead to overall savings to society because access to certain medications will be restricted, there will be mandatory generic substitution, and the increased negotiating power with pharmaceutical manufacturers will lower prices.

When I look at the assumptions behind the numbers in the PBO analysis, three jump out which don’t seem to account for how much pharmacare would really cost.

1) Restricted options for patients

The PBO assumed universal pharmacare would restrict the formulary to drugs covered on the Quebec formulary, which has been called the ‘”Cadillac” of public formularies, but which doesn’t cover as many therapies as private insurers do. The PBO also assumed that it would not cover drugs on the “exceptional list” in Quebec, which is a significant portion of public drug spending. This means that some patients will be forced to switch therapies, pay out of pocket, or stop taking a particular drug. I suspect the public will have little appetite for fewer choices. A survey commissioned by the Canadian Pharmacists Association found 74 percent of respondents were concerned that universal pharmacare would restrict their choice, and the vexation with losing therapeutic options has been evidenced in the rollout of OHIP+ (youth pharmacare) in Ontario.

2) Negotiating power with pharmaceutical companies would not change

The notion of increased negotiating power with pharmaceutical companies resulting from universal pharmacare is outdated. The PBO assumed that pharmacare would yield discounts on medications of 25 percent on average, but neglected to account for the fact that these discounts have already been achieved. Federal, provincial, and territorial governments banded together in 2010 to form a purchasing group called the pan Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance (pCPA), and have since negotiated billions of dollars of savings with both generic and branded pharmaceutical manufacturers. Generic manufacturers recently finalized a deal with pCPA for $3 billion in savings over five years. Discounts with branded manufacturers are confidential, however the latest Auditor General of Ontario report stated that the province harvested $1.1 billion in savings on $3.9 billion in branded drug expenditures in 2015–16, which equates to a discount of 28 percent. These savings are in line with a study that found discounts ranged from 20–29 percent in other countries. How much more room is there to negotiate cheaper prices if they already fall in line with international comparators? The real impact of pharmacare may not be delivering deeper discounts, but rather applying those discounts to drugs currently paid for by private insurance and out of pocket by patients.

3) Drug use will likely be much larger than the PBO estimated

The PBO assumed 12.5 percent increased utilization based on a study that measured price elasticity from policy changes in Quebec. Interestingly, the PBO used the lower end of the range from that study, whereas authors stated that the estimates could be magnitudes higher. Another study showed that Quebec had 35 percent greater drug utilization compared with the rest of Canada, which was driven by their policy for mandatory drug coverage in 1997 (a form of pharmacare). Given that 20 percent of Canadians report being uninsured or under-insured for drug coverage, a 12.5 percent increase in drug utilization seems low.

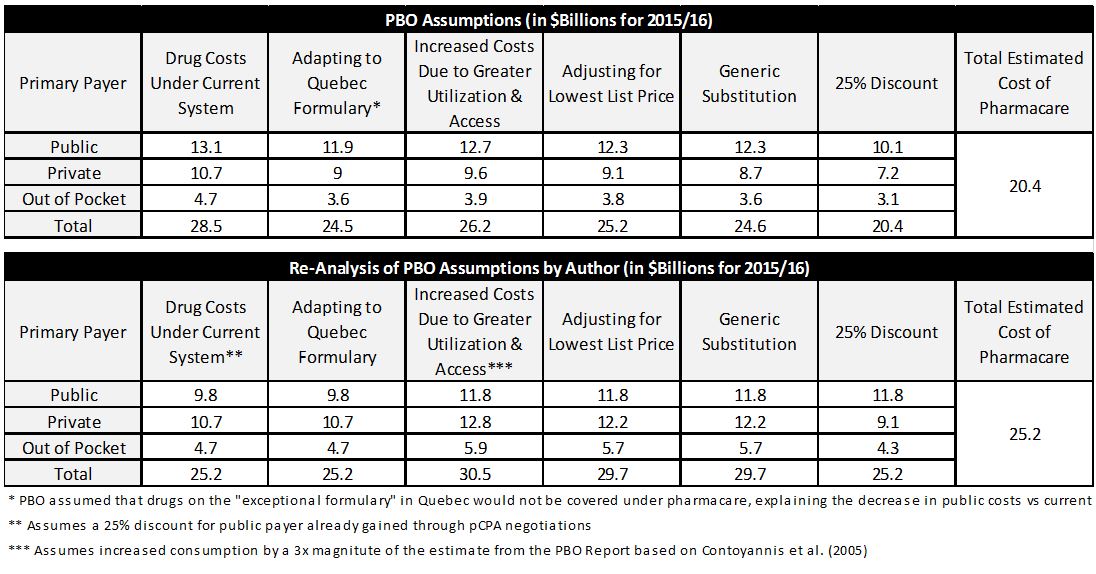

If we imagine a more realistic scenario, in which patients remain on their current medications, public payers already receive discounts but the discounts would apply to all drug claims, and the increase in utilization falls closer to what was observed in Quebec (35 percent), universal pharmacare would result in no change in drug expenditure compared with the status quo. Moreover, governments would see their incremental annual drug expenditure rise to $15.4 billion. The table below shows the PBO cost analysis versus mine.

Adapted from Table 3-6 from the PBO Report (page 42). Column headers were changed.

Some may argue that the PBO underestimated pharmacare savings because they didn’t account for the potential billions saved in lower administration costs for payers running the drug program. That may be true, but cutting administration sometimes has its drawbacks. A study on biologics for inflammatory bowel disease showed that publicly funded patients were more than twice as likely to require hospitalization and emergency department visits compared with privately funded patients due to a delay in receiving reimbursement approval, which can be attributed to the higher administrative support provided by private insurance. The counter to this argument is that broader access to drugs by currently uninsured and under-insured Canadians may lead to better compliance which could save costs through better management of diseases such as diabetes.

Universal pharmacare will not save money, but there is nothing wrong with that. The goal of universal pharmacare should not be to save money, but rather to improve equity and protect the vulnerable in society. But as we discuss how to implement universal pharmacare, we should assume that it will be net neutral, and governments will need to find $15.4 billion annually to fund it without creating political discord in an era of deficits.

*Peter’s views are his own.

The comments section is closed.

Do any of the economic analyses consider the need to invest in pharmacists? Pharmacist undergo significant training in pharmacotherapy and ought to be leveraged as medication stewards to ensure medication use is necessary, safe, and effective. I am concerned that discussions around Pharmacare focus heavily on drug cost and coverage, and less so on the “care” aspect of optimal medication management.

Full disclosure- I am a pharmacist working at a Family Health Team.

I love my pharmacist and his long time assistants because they know me on sight and help me and don’t give me grief and problems. They found the right liquid formulation for the baby’s meds and helped me find the right way to cut up and melt the other med so the baby would take it, I live a few miles away now, but it doesn’t matter, I go to them because I know they’ll make sure I am OK and that everything is done right and renewed on time. One time when it was closing, one employee got in her car and drove my desperately needed refill medication to me, after her shift was done, and the delivery guy was gone, just to be kind. So I’m sure they don’t think about pharmacists in their plans, but they should!

Following the Author’s lead, I am splitting up my comments.

Look, I get that we don’t see the savings, but that’s because of multiple factors, all easily regulated. One example? We don’t have a private insurance plan right now because we have a startup, and can’t get a group plan until we have more employees, and as a Family, we have too many pre-existing conditions, and could never ever be insured because of exclusions. So why isn’t there a private *group* plan for individuals that work for themselves and doesn’t allow exclusions for pre-existing conditions? I have no clue, but it needs to exist and unless regulated the damned industry won’t do it. Govt doesn’t like people who don’t have private plans, but if you can’t buy a private plan at any price, or even any reasonable price, then people will not start businesses or become entrepreneurs. If they do start them, then they risk severe illness, and in the end the only choice is some corporate job with benefits, or something low income enough to qualify a family for public benefits. And how does that make our economy progress—not at all, that’s how.

Then there are the forumulary lists of what is covered—that 91% figure is crap because it doesn’t account for the multiple delivery systems and dosages that so many people, children, or seniors or the disabled, or people with psych conditions need. And if I can’t swallow a giant pill because I choke and throw them up, then the liquid is necessary, mandatory, not some “nice option” to have. If I have a memory problem, then guess what, I need a time release medication, once a day, and no it is not a luxury or an unneeded frill. Generic companies could make those and do a better job on the few time release they make. Instead, they do a terrible job, so why are they rewarded by being placed on a forumulary? Price. So govt buys lousy drugs and patients forget to take them and govt has wasted money.

Another good example, hospitals still get mostly block payments, whether they treat 1000 patients or 100,000 it’s the same. “My” share of taxes is required to go to a local hospital that is hideous. I wouldn’t send my dog there, never mind my kids. My dollars should follow me to whichever hospital I go, just like doctor visits and drug purchases are allocated to me. Trust me, I have never needed online reviews to know where the best place is, none of us have. Since forever, people talk, gossip, spread word, discuss what happens with family, friends, acquaintances.

I grew up in a rural area, and yes we’d go to the local hospital for stitches, broken bones, but if we were really sick? We knew we needed to drive to a bigger city, like Hamilton or London and if we were really really sick we drove straight to Toronto to an ER on hospital row. Patients are smart people—lots of us have professional degrees and experience and we know a lot more than we are credited about Esp. corporations and trade and unions and mgmt and budgets and stats and biology, but somehow we are assumed to be stupid when it comes to health care.

Another example, everytime I read about the health budget going up and what a crisis it is—I am smart enough to know that our population is increasing, and so obviously costs will rise. And with a well run govt, so will tax revenue. Breaking down costs per person, and discussing what it saves when people get the right drug and the right dose at the right time will get us a lot further.

Question:

So why isn’t there a private *group* plan for individuals that work for themselves and doesn’t allow exclusions for pre-existing conditions?

Answer:

Because you’re asking everyone else in the plan to subsidize you when you know you’re already sick, and the only people who would enroll in the plan would have pre-existing conditions, and it would be prohibitively expensive? (‘death spiral’ in the health insurance literature)

Insurance doesn’t ‘work’ if you know that you’re going to have $10,000 in medical expenses next year.

In that case, the ‘fair price’ is $10,000, which is generally termed ‘unaffordable’.

Private insurance models work when 1/100 people is going to have $10,000 in expenses, no one knows who that is, and everyone is willing to pay ($100 + admin costs + profit) to make sure that an unpredictable bill doesn’t ruin their life.

Since it sounds like you’re in Ontario, you should definitely make sure you’re familiar with the Trillium Drug Program*(Government of Ontario). If you don’t work for a large company that can spread your costs across all of it’s employees, that’s the safety net for your family.

You’ll likely find that TDP does not cover all drugs and/or indications, and is generally more restrictive than private insurance, but I wouldn’t expect any ‘national pharmacare’ program to be more generous than existing public plans (especially if it’s targeted to break even financially relative to current expenditures).

So much to say, so little space…. To Durhane the increased numbers of epi-pens and inhalers being bought are a direct result of daycares and schools making it mandatory to have extras, stored at school, at all times. Schools/camps/daycares can’t just buy some Epi-pens, or inhalers, even though they are a standard dosage lifesaving medical device universally used. They do expire, (so bitter when we are sold a puffer that will expire within 3 months, omg I tell off those pharmacists) It’s expensive, and critical to have extras on hand, because in an emergency, they DO save lives, with seconds to spare. So no, as a parent of a kid with asthma and without private drug coverage, I won’t apologize for getting extras for free when I was allowed. Fewer ER visits at midnight or anytime actually is awesome.

This is an interesting opinion piece which touches complex cost issues. Unfortunately, none of the elements convinced me that the PBO should change anything to his report.

First, claiming that universal pharmacare would reduce current drug coverage without reducing costs is paradoxical and would require solid arguments to back this up. However, the arguments offered by the author are mostly problematic and generate misleading conclusions. Here are my comments to some of the claims in this opinion piece:

RESTRICTED OPTIONS?

-The author implies that covering more products is better. In the latest PMPRB annual report, we learned that 91% of new patented drugs commercialized in Canada in 2016 did not bring any significant therapeutic benefits as compared to what already existed in the market. By restricting access to therapeutically insignificant new drugs, a market provides greater financial incentives for drug companies to produce more therapeutically significant products, which would increase real options and therapeutic benefits for patients.

NO POTENTIAL SAVINGS?

-The author claims that PBO neglected to account for the fact that the discounts have been achieved, and cites an agreement of $3 bn in savings over generics that was passed four months after the publication of the PBO report.

– The agreement over generics was that, under the threat of being imposed tenders, generics manufacturers accepted to reduce their price by 38% on average only if public drug plans restrain from implementing a tendering process for generics in the last 5 years. The author claims that there is no room for additional savings, for example by implementing a tendering process. I disagree.

-The author misquotes a report by the Auditor General of Ontario by confusing data from 2015/2016 and 2016-2017. Total rebates for the public drug plan in Ontario in 2015/2016 was $900 millions on a total of $3.9 billion on brand-name drug expenditures. This equates to a rebate of 23%, which is at the lower end of rebates obtained by other countries.

-Based on numbers provided in the 2016 PMPRB annual report, the listed price (before rebates) of patented drugs were 25% higher in Canada as compared to the median of OECD countries. Canada thus pays among the highest listed prices in OECD countries and, in addition, public drug plans in Canada receive among the lowest rates of confidential rebates from brand-name manufacturers. The author claims that there is no room for Canada to obtain additional rebates. I disagree.

-The estimate of the PBO report that a universal drug plan could save an additional 25% on the cost of drugs (excluding mark-ups and dispensing fees) is absolutely reasonable if we consider that:

1-Significant savings would be achieved for drugs currently purchased without negotiations by private plans and uninsured patients.

2-An additional rebate of 25% on the price of patented drugs over the 23% rebate obtained by the Ontario public drug plan would mean that Canada would now pay a net price (after rebate) for patented drugs in line with the OECD median.

2-Since the publication of the report, savings of 38% has already been achieved for generics (and more could be achieved through tenders).

LARGER INCREASE IN USE THAN EXPECTED?

-First, Quebec is no illustration of universal pharmacare, it is an illustration of what happens with mandatory private coverage without universal pharmacare.

-The author measures differential use in Quebec versus Canada based on costs, which is non-sense because the study cited by the author explains a series of reasons behind differential costs in Quebec that has nothing to do with use.

-The author disagrees with the PBO estimates on differential use because it “seems low”. However, his alternative scenario on drug use seems a bit disconnected for different reasons:

1-while the author criticized a universal drug plan for reducing drug options, he now calculates costs by assuming that all patients would have access to the same drugs than before.

2-in his re-analysis, the author considers that people currently covered by private plans would massively increase their drug consumption by 20% if universal pharmacare is implemented. I disagree. In fact, a universal pharmacare program with the active management of a national formulary could allow the promotion of a more rational use of medicines, which would reduce (not increase) inappropriate use of drugs.

3-the author considers that the differential use should be based on what was observed in Quebec, and applies an increase of 20% for patients on public plans because use in other provinces would mimic what happens in Quebec. I suggest the author looks in particular to what it means for seniors, which represent 69% of beneficiaries for the Ontario Public Drug plan. Seniors in Quebec pay higher co-pays than in Ontario, have a higher cost-related non-adherence rate, but, according to IMS numbers, consume at least 30% more units. This means that higher consumption in Quebec is not linked to better coverage because Quebec has in fact worse coverage and higher cost-related nonadherence when it comes to seniors. The assumptions on which the author is building his logic are thus plainly false.

4-A better assumption would be to consider that drug use relates more to the role of physicians as gatekeepers and to the promotion of a rational use of medicines, which would explain why countries with low or no co-pays also have lower drug use than in Canada.

In a nutshell, the PBO analysis remains far superior to the alternative “re-analysis” provided by the author.

Universal Pharmacare would not only “improve equity”, and “protect the vulnerable” as the author rightly mentions, it could also allow developing our institutional capacity to promote a more rational use of medicines. And, yes, it could also generate very significant savings for all Canadians.

Marc-André Gagnon, PhD

School of Public Policy and Administration

Thanks for your comments, Marc-Andre. I appreciate your engagement in the debate on this platform, which demonstrates the value of healthy debates. I also respect your courage to debate the issue in a public forum. Let me respond to your critiques to move the conversation forward. I will do so in a series of comments since this platform has been finicky with longer responses.

Restricted Options:

Your argument is that 91% of new patented drugs are no better than current options, and therefore 91% of new drugs should not be included on any formulary. Yet, $4bn of the $28bn spent on total drugs in Canada are for drugs that would not be eligible for national pharmacare – that represents almost 15%.

The fundamental difference between our arguments is “who” we would rather make the choice for treatments. Under a national pharmacare plan, your option would be to opt for bureaucrats or advisors that advise the PMPRB or CADTH to make choices for patients by restricting options. Under the current system, treatment choices are left to physicians and patients.

This is a philosophical disagreement wrought with many arguments and I don’t think we’ll ever convince each other, but I also don’t think we need to. At the end of the day, it would come down to the electorate to decide. Some may prefer to defer to experts choosing their options, while others will want access to all of them. My point is, let’s not underestimate the population that will want to make their own choices.

Larger Increase in Use Than Expected

I disagree with your conjecture that Quebec is not an illustration of pharmacare. It is the only province in Canada with compulsory coverage for drugs, and the PBO used its formulary as the standard. It is not a perfect analog, as you rightly bring up issues with cost-related non-adherence, but its relevance stems from the fact that utilization increased significantly after it moved to compulsory coverage.

You may disagree with the Quebec paper that cites 35% increased utilization vs rest of Canada, but you neglect to respond to the PBO reference of 12% whereby the reference concluded that 12% is likely “magnitudes” lower than what may be expected.

Your argument is that pharmacare would lead to a rational use of medicines is without merit. National pharmacare may lead to a more selective formulary, however utilization would increase due to the elimination of cost-related non-adherence (coverage of all those uninsured or underinsured) and also wastage. We will get a sense of the impact of utilization of OHIP+ when estimates committees resume after Sept 1. Anecdotally, we have heard from pharmacists that asthma puffers and EpiPens were flying off the shelves because they were “free”. Without any copays, we can imagine a similar scenario with national pharmacare.

I would be interested in seeing your references for the examples you raise with regards to seniors.

The PBO did not account for any current savings through pCPA, whether they be 23% to 30%. With the PBO assumption of 0%, the calculations are not reflective of the Canadian market. Moreover, to suggest an additional 25% can be negotiated, for a 48% total average discount, is without merit. Literature shows that discounts of 20% to 29% put us in line with OECD, and the negotiated rates of generic drugs have no impact on the innovative molecules market. We cannot choose a value (e.g. 48%) to fit our desired model.

In a nutshell, I am not claiming that this re-analysis is superior to anything else. I wanted to address the fact that, under another realistic set of assumptions, we should imagine a scenario where pharmacare does not save money. If we go down this path, it should only be to improve equity, and not for economic reasons.

We should also admit that the PBO missed the mark in certain respects. They should have costed more models, whereby they looked at a scenario whereby patients would make their own treatment choices. The fact that they did not account for current pCPA discounts was an oversight. Lastly, assuming only 12% increase in utilization is not supported by the very reference they based it from – hoping that physicians will lead us to a more rational use of drugs is not something we should bank on.

In conclusion – let’s keep the dialogue moving and see if the broader community can come to a consensus on assumptions. As we do so, let’s also be transparent about our conflicts of interest. Mine have been disclosed in the article. I would appreciate if those that comment also disclose theirs. The latest version of Marc-Andre’s conflicts can be found in the following link, which discloses funds accepted from the Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions.

Conflicts- http://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/421/HESA/Brief/BR8201423/br-external/CarletonUniversity-Gagnon-9341046-2016-04-18-e.pdf

We certainly disagree at a philosophical level, but that is not issue. The issue here is that you criticize an economic analysis based on false statements about use and prices. Here are the last comments I will make about your opinion piece.

-On the PBO reference of 12%: I think you are simply confused. Contoyannis et al. mentions that price elasticity is between -0.124 and -0.164. The PBO report builds on that study and others to show that by reducing co-pays by 100% on some products and 65% on others, we would observe an “overall weighted increase in consumption of prescription pharmaceuticals of 12.4 per cent”. They used Contoyannis et al.’s average elasticity rate of 14% (not 12%). You are confusing an elasticity rate with a weighted overall increase, and based on that confusion you accused the PBO of arbitrarily using the lower end of the elasticity rates and thus of underestimating the increase in consumption. This is not a helpful contribution to the debate.

– I suggest you have a look at what happens in healthcare systems where there is no co-pay on cost-effective prescribed products, for example in Wales, Scotland or Netherlands. Please tell me if you find massive waste, as you suggest would happen in Canada. And, by the way, the PBO model still includes co-pays.

– The PBO model looks at what it would cost the Federal Government if we achieved a 25% discount on ex-manufacturers’ prices for all drugs. Contrary to your claim, they do not say anywhere that it is an additional rebate over current confidential rebates. Contrary to your claim, PBO also ran other “realistic scenarios” with rebates of 10%, 20% and 30% for sensitivity analysis (see tables A-3 and A-4). Note that a peer-reviewed paper also ran different realistic scenarios to determine the cost (and savings) of implementing universal pharmacare in Canada and the results show that PBO might be underestimating potential savings: http://www.cmaj.ca/content/early/2015/03/16/cmaj.141564

-Again, while the official listing price on patented drugs is on average 25% higher in Canada as compared to other OECD countries, once we correct your misquote of the data by the Ontario Auditor general, the level of rebates received by the Ontario public plan is at the lower end of what is received on average in OECD countries. Claiming that Canada is now doing as good as other OECD countries is problematic since Canada not only runs slower, but also starts way behind other OECD countries.

-On Quebec not being a universal pharmacare system, as well as its impact on seniors (with references), as well as the amount of additional savings that could be made in Quebec with a universal pharmacare system, see: https://cdn.iris-recherche.qc.ca/uploads/publication/file/Note_Assurance-me_dicaments_201712WEB.pdf

-I do not think it is worth commenting on your view that the recourse to health technology assessment by health insurance systems does not help physicians in improving their prescribing decisions both in terms of therapeutic benefits and cost-effectiveness of products.

Marc-André Gagnon, PhD

School of Public Policy and Administration

None of my critiques were based on false statements, and all of my arguments were peer reviewed prior to being published on this site.

– As far as price elasticity, there is no confusion. “Based on this research, the overall demand price elasticity for prescription drugs in Quebec is estimated to range between -0.11 and

0.16. That means for a 1 per cent increase in the price a patient pays, the amount of prescription drugs consumed would decrease by between 0.11 per cent and 0.16 per cent.” Considering price reductions from 65 to 100 percent, the PBO got to a 12% increase. My issue is that the -0.11 to 0.16 range could be 1 to 4 magnitudes higher, which would translate to a significantly higher consumption.

– Wastage is not even a factor in these calculations. It is a factor that we may want to consider in a series of puts and takes by converting to pharmacare. Keep an eye out on Sept 1 when the utilization from OHIP+ in Ontario is made public. I would prefer to use Canadian examples versus international examples.

– My claim on the discounts calculated by the PBO is the strongest aspect of my argument. The PBO did not factor in current rebates into their calculation. Look at the table of their financials – not once do they subtract the current savings. Given that pCPA is already driving discounts, 25% is not realistic.

– I would wager you a friendly bet that the vast majority of physicians in Canada do not know of CADTH or its reviews, and would not consider their reviews in their prescribing behaviour. If the basis for your argument is that physicians will prescribe only cost-effective medications as described by CADTH, then we are in trouble. This area may be worth studying deeper.

If this is the case then the whole health care system payment should change which means making the health care system private

Thanks for your comment, Hassan. Can I assume this is Hassan Yussuff, President of the Canadian Labour Congress? Great to see organized labour taking an active role in the advocacy of pharmacare.

I respectfully disagree with your argument. Health care is a public good, which is subject to market failure. It is most efficient under a single payer system. We can’t equate this specific scenario of converting from status quo to national pharmacare to our overall health system. Pharmacare is a delivery of goods, versus a delivery of services. I am arguing we go forward with pharmacare, but we shouldn’t assume we will save money. The increased efficiencies gained from a single payer will be offset by higher volumes. Moreover, workers will not have the same options they currently enjoy with private coverage.

Peter: Pleased to see a broader commentary on national drug benefit program.

A few years ago the head of the VA in the United States described pharmaceutical benefits for veterans. The VA is the largest drug benefit program and gets 22% discount of list price on drugs. They provide comprehensive coverage at no charge and distribute medications by mail from hospitals. Sounds like a wonderful system.

This was followed by the statement that this was the largest problem area because they had no idea of what happened to the tons of medication they sent out. Some was used appropriately, some was saved, some discarded, some diverted and some misused. A very high expenditure resulted from patients admitted for drug related problems.

Why do we want a system like this?

In 1975 Saskatchewan introduced a universal benefit program with province wide purchasing for all the benefit drugs. Sound familiar? What happened to it? What can we learn from this? Why isn’t this “evidence” part of the discussion?

I don’t think a comparison of the veterans’ situation is at all contributing to the discussion.

The US is perhaps the worst country in health care coverage, and veterans are such a specific and unique demographic. To say this is to say the US and Canada are comparable, and that veterans are somehow reflective of a general population. As well, what is the average rate of drug misuse in the US? How regulated is the prescriptions for drugs sent out from hospitals? To say the least, this is a cherry-picked example that was never constructive in the first place.

Everyone has biases and it’s important to disclose them. Mr. Dyrda did this. However, to assume he’s wrong simply because of his employer may be convenient, but a much greater error. This is a thoughtful commentary and it deserves careful assessment…which is the point of HealthyDebate.

On the public wanting extensive choices- I am not persuaded. For most conditions I would argue there is too much choice, with many expensive drugs offering marginal if any additional benefit.

On negotiating power- how come our prices remain so high compared to other countries? The comparator countries used by our pCPA tend to be those with high prices.

Tha challenge in moving to a national pharmacare program will be in moving the savings made by employers, insurance companies and individuals to offset increased government costs

Thanks for your comment, David. It is certainly true that some conditions have the luxury of many options, and not all of them may be the best choice for a patient. However, I caution us as Canadians to keep our options open, as we have a very heterogeneous population. With the impact of pharmacogenetics on drug efficacy, we should try to keep our formularies broad but provide clear guidance and criteria for optimal use. Some look to the New Zealand pharmacare model as a good example, but their population is much more homogenous than ours so having access to options isn’t perceived to be as big of an issue.

In terms of pricing – by law (Patent Act) enforced by the PMPRB, Canada must not exceed the median price of comparator countries. Furthermore, savings from pCPA are not transparent, so the net price paid is significantly lower than we see with the list price. I would argue at a 28% average discount, our prices in Canada should be within the 20-29% range we see in Europe.

Moving money from private to public to fund pharmacare will indeed be a challenge. Today, a Globe and Mail article showed that there may need to be a tax increase to fund this gap. Considering the Federal government is running $20bn deficits already, adding another $15bn with pharmacare will be a significant task.

History is replete with government initiatives, provincial and country-wide, that were going to save loads of money, but instead yielded no savings or (more often) increased costs…

Lots of wild promises being thrown out there about national pharmacare…most likely they will not come true…

Thanks for your comment, Paul. I would argue this will be a balance of puts and takes. There would be a reduction of price, but an increase in volume… where it nets out would be a balance of the two. Compared to other government initiatives, I would think that pharmacare may be unique.

Thank you for your article Peter. It is very important to cover multiple aspects of the argument. Here’s something that seems to be missing generally: a move to get patients off medication to improve overall health. There’s huge savings and social benefits to improving diet, smoking cessation and getting regular exercise. We might incent this behaviour by cutting paying fees per script written which I believe is the case in Ontario. Then we will have funds available for young and old to be looked after. I would really love you to do some research and a piece on that. Best.

Hello Civi. Thanks for your comment. You raise a good point. There is a movement towards de-prescribing in the medical community. However, that tactic for cost saving would likely be independent of any pharmacare model. Therefore, we wouldn’t consider it when conducting a calculation of the cost of pharmacare.

The detailed analysis is so very helpful. As patients, we know intuitively that you can’t provide the “same” coverage for “less” $ especially when the purpose of Pharmacare is to include all those patients who are currently not accessing. But the data and analyses provide some substance to intuition! Also, we don’t have the results (and will likely never have full learning) from the experiment with Ontario’s OHIP+ whereby kids who were added to the public plan, including those who already had private coverage. But we have heard some interesting “stories” about the access to asthma inhalers increasing by “double digits” in the first quarter and use of EPI pens for four months equaling the use for the entire last year, contributing to the shortage in EPI pens in Canada (other factors played into this). So thanks for the deep dive and for making it understandable.

I understand Mr Dyrda works for, ultimately, Johnson & Johnson, hardly an independent third-party voice in this debate. while we ought to focus on the content of his argument, that argument replies on several studies supporting his more contentious claims — do we really have the time to sort through his supporting studies, given a natural assumption of his lack of impartiality on this subject due to his relation which a major pharma corp? It wouldn’t be possible to get an opinion on this important subject from a clearly-unbiased source, or add comments from such a source, given Mr D’s associations?

Hi Fred. Thanks for your comment. Reimbursement in Canada is very complex and managed by a relatively small group of professionals. I would argue that anyone involved in the pharmacare debate will have some sort of bias. Given that establishing national pharmacare would require a shift of $15bn to government spending, I would argue we should take lots of time to ensure we have the right assumptions going in. I would also argue that it is beneficial to us all to take into account all perspectives. As much respect we have for academics in this field, they too, are not without their own biases.

Let’s look at some of the data that Peter Dyrda used. He does note that savings may be realized in the prices that are paid by private insurance and people who pay out-of-pocket but doesn’t estimate those savings. According to CIHI in 2014 private insurance and out-of-pocket payments equalled $18.4 billion. A 28% savings on that (the 28% is Dyrda’s estimate of savings in the public sector) is $5.2 billion. Dyrda also says that Quebec had 35% greater utilization than the rest of Canada. Actually what the study said was that Quebec spent 35% more per capita than the rest of Canada. The authors cite multiple reasons for the higher per capita spending – higher volumes of drugs prescribed, more expensive treatment options chosen by prescribers, higher unit prices and lower use of available generics. Only the first of these was mentioned by Dyrda. Dyrda also cites another study about the use of biologics for inflammatory bowel disease as showing that public drug programs cut administration. But while the study says that those on private insurance received biologics more rapidly, it didn’t say that public programs cut administration. That’s Dyrda’s interpretation. Also the study noted that since it was completed it is now easier for doctors to prescribe some biologics for IBD. Again, that’s not something that Dyrda pointed out.

I think the bottom line is that we need better data to enable more realistic and inclusive cost estimates, with explicit assumptions and appropriate sensitivity analyses. For example, the PBO report doesn’t assess their savings estimates if their 25% universal price cut assumption takes a few years to negotiate, or applies only to a subset of drugs (i.e., new ones). It doesn’t explain what may happen to patient out-of-pocket costs if $3.9 B in drugs now paid by private drug plans are no longer eligible under the QC formulary. These are big questions. Right now we have to get better answers and work much harder at finding common ground so that the Advisory Council can make a really compelling case to politicians and ensure the continuing support of Canadians.

Thanks for your comment, Joel. I attempted a long response but it hasn’t uploaded onto the page, so let me try again with a more succinct response. I appreciate your thoughtful comments on the assumptions – this is the scrutiny that I felt was missing from the HESA report. To respond to your comments: for the utilization assumption of 35% – aside from 5% being attributed to an older population in Quebec, the authors hypothesize that the remaining difference is due to using more expensive treatment choices and compulsory coverage, which would be a relevant analogue for national pharmacare. The 12.5% assumption used by PBO was taken from another study which stated that naiive OLS estimates could have been 1-4 times higher than that. I would argue that the estimate should be closer to 35% than to 12.5% based on these two studies. As for the IBD administration paper – I never inferred that the study measured the impact of cuts. The paper highlights that private insurance results in faster time to drug which improves outcomes – and the hypothesis is that this is the case due to more investment in administration by private insurance versus public. If we moved to national pharmacare, we would see a reduction in administration, and therefore presumably a longer time to drug, which could lead to worse outcomes.