*Editor’s note: Provincial licensing of medical professionals, including doctors, may become a barrier to redistributing our work force during this pandemic. Rather than one large outbreak, COVID-19 will cause many small ones that will vary in scope, size and duration. Some regions of Canada will have a greater need for personnel than others, and demand for virtual care professionals will increase. We bumped up this piece because this debate is relevant now.

When Kyle Sue’s mother was diagnosed with stage four cancer, he was working in Nunavut as a family doctor. He immediately made plans to return home to support her. But as the only family physician serving his community, he needed to find someone to cover for him. This was not an easy task, in part because the process to obtain a medical license to practice in Nunavut requires extensive paperwork, fees, can take months to obtain, and requires that you hold a valid medical licence in another province or territory.

Ultimately, Sue could not find someone to temporarily cover his practice while he was away, and as he painfully put it, “I just had to abandon my community.”

Gaps in physician coverage happen all over Canada, but is more prominent in rural areas, like Nunavut, because of the overall shortage of rural family doctors.

Having worked in urban and rural settings in Ontario and BC, Sue finds that the process to obtain a license in another province to be both “prohibitive and expensive.” He is a proponent of creating a national medical license – one single license to practice in any jurisdiction in Canada, without undergoing the onerous applications or paying multiple annual fees. He sits on the Board of the Society of Rural Physicians of Canada (SRPC) – an organization that has been advocating for the creation of such a license for years.

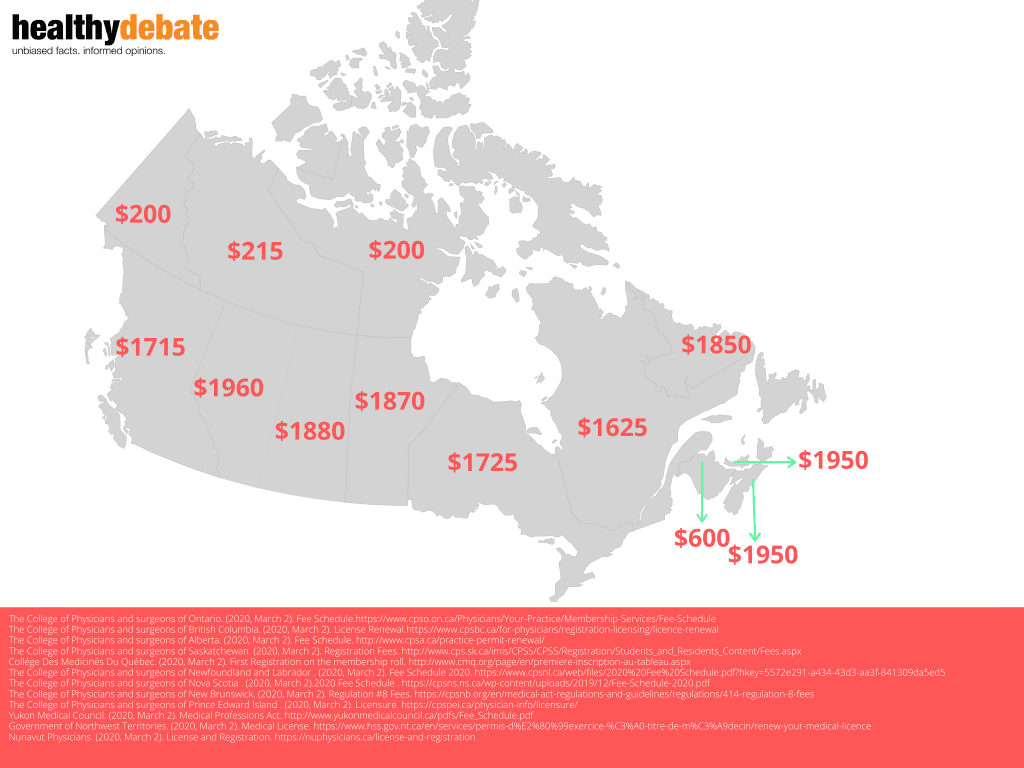

Currently, each of Canada’s 13 provinces and territories have their own set of physician licensing requirements and fees, despite all agreeing to a national standard of licensure in 2009. Ontario requires upwards of 40 documents to apply. According to Sue, almost all of the other provinces are similarly cumbersome. Doctors usually have to complete additional paperwork to get credentialed at their individual hospital.

The fees can also be in the thousands. For example, applying for a full license in Alberta requires an annual fee of $1960, $395 to review qualifications, $160 per document to verify credentials and $800 to register in Alberta upon successful application. For physicians who practice in multiple jurisdictions, this cost becomes significant.

Advantages of a National Medical License

According to a 2016 report from Statistics Canada, around 4.8 million people across the country do not have a family doctor, and the majority of those reside in rural areas. This is despite the fact that since 2014, the number of new physicians have increased at a faster pace than the population. The reason for this is that 92 per cent of all physicians in Canada work in urban centres.

One of the biggest proposed advantages of national licensure is the potential to increase physician access to underserved and remote communities. By removing the barriers to licensure, the hypothesis is that physicians will be more easily able to work or locum in underserved communities. If a family doctor is exposed to a rural practice early in their career, they are also more likely to work there long term.

Many of the country’s largest medical organizations, including the SRPC, the Canadian Medical Association (CMA), Resident Doctors of Canada (RDoC), and the Canadian Federation of Medical Students (CFMS), are in favor of a national medical license in some form.

“These barriers [to getting licensed] exacerbate the already significant lack of physicians in underserved communities, which will ultimately impact patient care,” says Mike Benusic, the RDoC lead on national licensure, and a public health resident in Toronto. He says RDoC believes that mobility between provinces should not be this difficult and in fact, may be violating the Canadian Free Trade Agreement (CFTA) by restricting labour mobility.

Sandy Buchman, CMA President, agrees. “It would be common sense that if I’m safe to practise in Ontario, then I should be safe to practise in British Columbia,” he told CMAJ.

Jane Philpott, family physician and health advisor to the Nishnawbe Aski Nation, agrees with the implementation of national licensure. “It would have significant advantages, particularly to address the workforce shortages in underserved areas,” she says. “It makes sense and needs to be done across all health professions, not just for physicians.”

Nurses also need to be provincially licensed in order to practice. The Canadian Alliance of Physiotherapy Regulators is working with provincial bodies to create a cross border registration category for physiotherapists. While pharmacists are provincially regulated, there is a pathway for pharmacists and pharmacy techs to practice in other provinces through the CFTA if they complete an ethics and jurisprudence exam, among other requirements.

A national licensure system for physicians isn’t without precedence. Supporters often point to Australia’s example, termed “National Registration,” in place since 2010. Michael Kidd, Chair of the Department of Community and Family Medicine at the University of Toronto, used to work in Australia as a family doctor. He was also President of the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners where he was instrumental in the development of their national licensure system.

“In Australia, we had a similar system that required separate registration for each state or territory, which was expensive, time-consuming, and a disincentive for people to practice across borders. Also, Australia, like Canada, had a real problem with work-force distribution, particularly with challenges in providing medical services in remote areas,” he says.

According to Kidd, a system of national registration “just made sense for Australia — one country, one set of standards.” He further points to the United Kingdom as another example, where they have a General Medical Council that allows licensed physicians to freely practice not just within one country, but in any of the four countries in the UK.

A recent CMA survey of 6,700 physicians found that 91 per cent support a national licensure system as they believed it would improve access to care for patients. Of this 91 per cent, 45 per cent stated they would do a locum, 30 per cent said they would practice in multiple jurisdictions on an ongoing basis, and 42 per cent reported that they would practice temporarily in a rural or remote area in another jurisdiction.

Support for national licensure isn’t limited to physicians. The four Atlantic Premiers have publicly voiced their support for increased physician mobility throughout the country as a means to improve patient access to healthcare.

Is there a downside to having a national medical license?

While some agree with national licensure in principle, they caution that there may be unintended consequences for physicians, governments, health systems, and for the public.

Barry Pakes, a public health and preventative medicine specialist and rural emergency physician, says that it will reduce the authority and role of provincial colleges. This can further complicate health human resource planning for provincial ministries.

“Provinces fund post-graduate training spots based on current and projected provincial needs – if graduates can more easily move between provinces, this changes these calculations dramatically,” says Pakes.

Pakes sees the logic behind using national licensure to improve healthcare access to remote communities – but says it’s not so simple. “If we decrease these barriers, you may make it easier to recruit,” he explains, “but you may also motivate people to move around more and to explore different settings. This may be great for practitioners searching for the right setting to work, but it can create even more transience and instability for patients in the very communities this change is seeking to help.”

“What we need,” Pakes reiterates, “is health human resource planning on a national level, and we simply don’t have that yet… tinkering with licensing may be an effective bandaid or may open a whole new wound.”

Fleur-Ange Lefebvre, CEO of the Federation of Medical Regulatory Authorities of Canada (FMRAC), echoes his concerns. Her organization, comprised of the provincial and territorial regulatory colleges, is integral to the creation of a national licensure agreement.

“Creating one national system would be a significant constitutional challenge because currently, regulation is a provincially mandated responsibility. It is going to be easier to work within the construct that we have now, which is that professional regulation is something that the provincial and territorial governments do, and not the federal government,” said Lefebvre.

Philpott, also Canada’s former Federal Minister of Health, disagrees. “The constitution doesn’t need to be overhauled,” she says. “There’s certainly lots of room within the constitution for a strong federal role through significant federal funding for healthcare and federal spending power. There’s constitutional authority to participate in and be involved in addressing health workforce challenges. I think the barrier is inertia and status quo, which takes a bit to overcome.”

Have we made any progress toward a national medical license?

FRMAC is exploring the creation of two new licensure agreements. The first is the Fast Track License Agreement. This is intended for physicians who wish to hold a full license in another province or territory. It would provide a faster, simpler and less expensive application process. Lefebvre stated that the process would be around five questions and that the application fee would be about 50% of the regular fee, though the licensing fee would remain the same. However, to qualify for this fast-track license, a physician will have needed to hold a clean slate of practice in their home jurisdiction for at least three years.

The second is the License Portability Agreement, that provides another license for physicians wishing to pursue a short-term locum in another province or territory. To be eligible for this license, a physician must practice in their home jurisdiction for at least two thirds of the year. The cost of holding this additional license may be more than the cost of a regular license.

FMRAC is also exploring the possibility of creating a single licence to support cross Canada telemedicine.

For Benusic and RDoC, while this is a significant step forward, there are still some concerns. “We applaud FMRAC for the creation of these agreements. This will certainly help physicians wishing to practice in a different setting.”

But he says RDoC will continue to advocate for one single licensing system and the removal of the number of years in practice criteria in these agreements. “This unfairly discriminates against residents and newly graduated physicians, and as of yet, there has been no evidence-based reason given for the existence of this three-year requirement. Nowhere else in the licensing system do we discriminate based on years of practice,” he says.

It remains to be seen if these new agreements proposed by FMRAC will make it easier for doctors, like Sue, to find coverage for a busy rural practice. Despite being a country that prides itself on national healthcare, we have a patchwork of provincial health care systems. It is difficult and expensive for all health professionals, including physicians, to practice across our provincial and territorial borders…and ultimately it is patients, particularly in rural and remote Canada, who pay the price.

The comments section is closed.

When I took my vehicle between provinces my vehicle had to be reregistered by the new province and I had to get a new driver’s license.

In this era of self driving cars, it is only logical that my vehicle also has to get a driver’s license, which means vehicles must be able to fit through the doors of the ICBC Driver Licensing locations

If that doesn’t seem logical, you may be suffering impairment of sense of humour, or I may be suffering from poor humours (only physicians can diagnose diseases of the humours). Either way, I would suggest you consult with a doctor, and get enough second opinions to see if it is unanimous that their lives would be better if they were licensed to practice Canada-wide. I have wished I had a family doctor since I moved to Canada over 10 years ago, and going all the way from AB to BC I still haven’t found one.

When I took my vehicle between provinces my vehicle had to be reregistered by the new province and I had to get a new driver’s license.

In this era of self driving cars, it is only logical that my vehicle also has to get a driver’s license, which means vehicles must be able to fit through the doors of the ICBC Driver Licensing locations

If that doesn’t seem logical, you may be suffering impairment of sense of humour, or I may be suffering from poor humours (only physicians can diagnose diseases of the humours). Either way, I would suggest you consult with a doctor, and get enough second opinions to see if it is unanimous that their lives would be better if they were licensed to practice Canada-wide. I have wished I had a family doctor since I moved to Canada over 10 years ago, and going all the way from AB to BC I still haven’t found one.

When I took my vehicle between provinces my vehicle had to be reregistered by the new province and I had to get a new driver’s license.

In this era of self driving cars, it is only logical that my vehicle also has to get a driver’s license, which means vehicles must be able to fit through the doors of the ICBC Driver Licensing locations

If that doesn’t seem logical, you may be suffering impairment of sense of humour, or I may be suffering from poor humours (only physicians can diagnose diseases of the humours). Either way, I would suggest you consult with a doctor, and get enough second opinions to see if it is unanimous that their lives would be better if they were licensed to practice Canada-wide. I have wished I had a family doctor since I moved to Canada over 10 years ago, and going all the way from AB to BC I still haven’t found one.

This is a very informative blog, thanks for sharing about It will help a lot; these types of content should get appreciated. I will bookmark your site; I hope to read more such informative contents in future.

I support fully the creation of National Medical Licence. It can work like this. Physician holds a clean licence in a province can apply for licence in another province after submitting an universal application (same for every province). The applicant will not require to provide any further verification of credentials. Colleges can communicate directly to seek confirmation of applicant’s registration status.

The second licence registration fee would be half of the regular fee. Once registered, any practice related issue regarding the physician is under the full jurisdiction of province where patient resides

Excellent idea. The same should be considered for the nursing profession as well.