In this series, AMS Healthcare addresses the challenges facing healthcare today – particularly in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. The AMS Community promotes compassionate care, development of the leadership needed to realize the promise of technology and the understanding of how our medical history influences the future of our healthcare. A new piece will be posted every Friday on Healthy Debate.

How are you? How am I? Quite literally, where was I today? These question marks are a sign of my own disorientation – dis-place-ment in this new virtual landscape that feels like everywhere and nowhere. I spent 12 hours today zooming from appointment, to meeting, to appointment (and managed my children’s virtual schooling).

As a psychiatrist, for the past 10 years I have led what has become our hospital’s virtual mental health care program. The roots of this program originate in the work of compassionate and intrepid psychiatrists beginning in the 1970s, who drove, flew and even dog-sledded to provide mental health care to rural and underserved communities. As I became involved as a new graduate in this work, the time also had come to consider the possibilities that digital health offered to extend this work and provide greater continuity of care. Telemental health grew slowly to meet that need. Some ambivalence lingered, however. My interest in digital compassion, along with my colleagues Gillian Strudwick and David Wiljer, arose out of this ambivalence and a commitment to ensuring that we could still provide virtual care that is compassionate and person-centered, even if this meant being “present” in new ways.

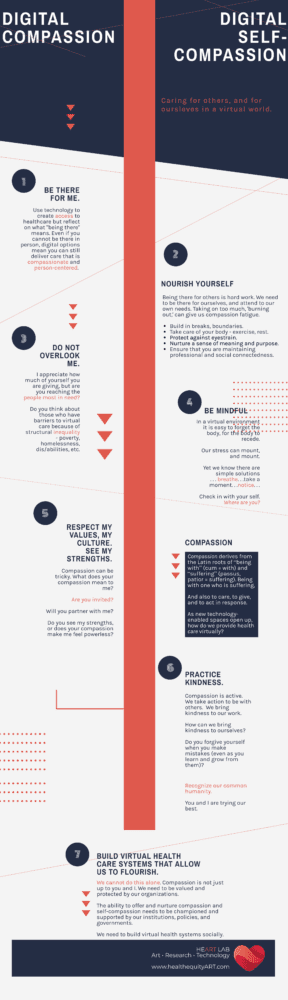

Compassion, which literally translates to being with the suffering of others, is other-oriented. It appeals to us to  act in response to the needs and feelings of others. Digital compassion seeks to use virtual means to be present and to respond to the suffering of others. Virtual healthcare enables us to provide compassionate care and to convey that compassion in spite of limitations that may exist in virtual modes of health delivery.

act in response to the needs and feelings of others. Digital compassion seeks to use virtual means to be present and to respond to the suffering of others. Virtual healthcare enables us to provide compassionate care and to convey that compassion in spite of limitations that may exist in virtual modes of health delivery.

Even at the best of times in outreach, however, compassion is tricky. In Indigenous communities in particular, compassion has a long history that is uncomfortably associated with churches, institutions and with social policies that attempted to assimilate in the guise of delivering aid and care. The resonances of colonization in the present mean that compassion can be disempowering and paternalistic. Compassion, it turns out, can have unintended consequences. Compassionate care in these, and any contexts, must be invited, must be collaborative and must acknowledge the inherent worth, autonomy and strengths of the recipient of care (and community).

And then, COVID-19 happened. Everything that our program had learned about digital health allowed us to rapidly transition to virtual healthcare across our organization, growing from 350 virtual visits per month to almost 4,000 virtual visits per month in a matter of weeks. It feels compassionate to be able to continue to meet urgent healthcare needs while also contributing to the safety of our colleagues and patients through physical distancing. This work also feels supported by our institution, our partners, our government.

But it seems the more that we learn about compassionate care, the more we recognize barriers to compassion. Those with means to access technology during the current pandemic, and with the comfort and ability to use it, received care more readily than those who face poverty, language barriers, homelessness, disabilities and other structural inequities. Compassion compels us to act to reduce these barriers.

Compassion gives us purpose and meaning, it is why many of us went into healthcare. Compassion is also hard work. We know that as health providers shoulder this work, they can also experience burnout at high rates and that this can be associated with declining compassion or compassion fatigue. Compassion fatigue can not only get in the way of providing compassionate care, it can wound patients.

So as the weariness of newly long virtual days set in, I began to reflect on some unintended consequences for myself. In an effort to be ever (virtually) present, I had also neglected myself. You do not need the full list, but certain choices and behaviours – comforting foods, long periods of immobility, no breaks, looking at screens for protracted periods, lack of sleep – took a toll on my body and mind. I was immobilized, yet felt restless; frantic, yet inactive; present, yet absent. Early reports suggest that these effects are widespread. It is highly likely, although further research is warranted, that factors associated with virtual care can also lead to or contribute to health provider burnout. This self-reflection leads me to conclude that without digital self-compassion, there can be no digital compassion.

The infographic is my attempt to balance what we know about the best in digital compassion, while applying knowledge on health provider wellness and burnout prevention to self-care in ever-increasing virtual environments. The rapid transition to virtual healthcare is unlikely to recede to pre-COVID-19 levels. We need to learn to care for ourselves in these virtual landscapes so that we can continue to provide compassionate care from wherever we are.

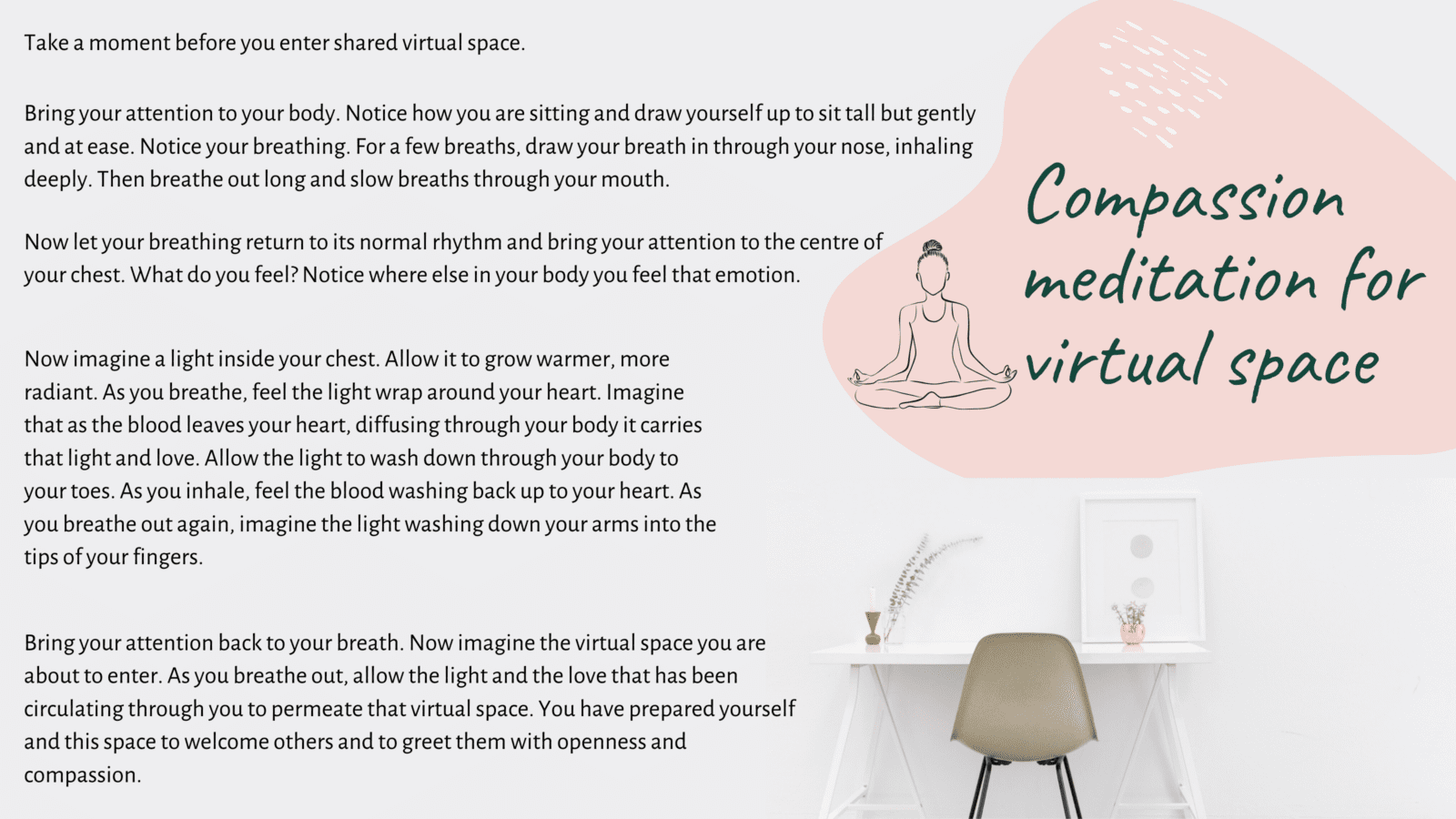

In my own practice, I have developed and adopted a very brief meditation to cultivate a sense of compassion, including compassion for myself.

The comments section is closed.