As a crisis line counsellor at the assaulted women’s helpline, Susanna comes home “emotionally and psychologically exhausted” from the stories she has heard during the COVID-19 pandemic.

She recalls a desperate phone call from a woman new to Canada right after she left her home and abusive husband. As Susanna, not her real name, describes it, the situation mixed “economic dependency, immigration dependency, and isolation,” a combination she sees all too often.

In what the United Nations is referring to as the “shadow pandemic,” gender-based domestic violence rates are rising worldwide during the pandemic. In Ontario’s York Region, police have reported a 22 per cent increase in intimate partner violence (IPV) incidents; federal reports show a 20 to 30 per cent increase in rates of gender-based and domestic violence.

Yvonne Harding, manager of resource development at the Assaulted Women’s Helpline, says women who were previously able to cope with their situation are now calling in to report increasingly dangerous situations.

Research has shown that in many settings, gender-based violence tends to increase following disasters. During the COVID-19 pandemic, physical distancing measures have left many women confined with their abusers with reduced access to social supports and the outside world. As Harding puts it, “isolation is already such a huge tool in the abuser’s toolbox and it’s been handed to them on a silver platter.”

The pandemic has also added financial stressors with one or both partners facing job losses. Or, as in the case of Susanna’s caller, increased financial dependency on the abuser.

Dr. Janice Du Mont, a public health researcher specializing in IPV, has found that caregiving roles have made many women ineligible for emergency financial benefits while many others work in jobs without paid sick leave, making them vulnerable to financial abuse and exponentially more difficult to leave an abuser.

Du Mont adds that we need to consider the impact of COVID-19 and associated stressors that push men to feelings of “depression, impotence and desperation” including job loss, fear of illness and absence of social support.

Shelters are also stretched to capacity, meaning there is no place for escape. And it is more difficult to access services when isolating with an abuser because phone calls and text messages can be monitored. Susanna says she has received calls from women taking out the garbage or hiding in closets or in the bathroom, forcing what would normally be a 20- to 80-minute call to be completed in just a few minutes.

Several innovative solutions taking advantage of virtual connections to strangers, loved ones and healthcare providers have arisen out of this crisis.

Calyn Blackburn, a survivor of domestic violence, remembers her abuser isolating her from her friends and family and wondering how she could help victims during this pandemic. In March, she posted on Facebook asking victims to contact her about a sale of make-up if they needed support. Her abuser used to monitor her Facebook messages so she was aware of the need for code words. The post has been shared more than 70,000 times.

However, posts like this have been criticized because they may result in an untrained person dealing with potentially dangerous situations and the possibility that abusers might gain knowledge of the system.

Blackburn understands these criticisms but says that despite the risks, she will keep her post up and continue to respond to messages given that the benefits could be lifesaving.

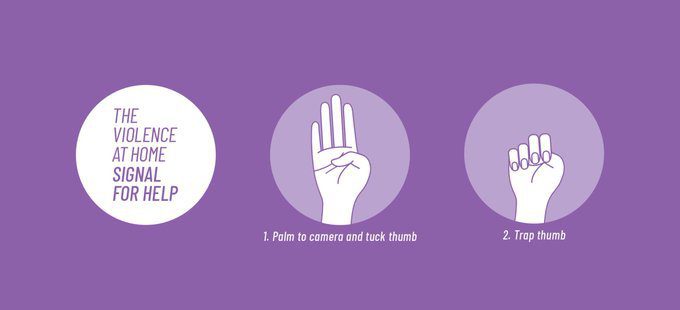

The Canadian Women’s Foundation has also taken advantage of the increase in video calls and has developed a one-handed signal that allows victims to covertly identify themselves as needing a check-in or additional support.

Sarah Ruddle, director of marketing and communications at the Canadian Women’s Foundation, says that while this is not the perfect solution, it is a tool that may be useful during physical distancing. “This new reality requires new methods of communication to help those facing gender-based violence,” she says.

Kim Katrin Crosby, an artist, equity consultant and survivor of domestic violence, is developing an app inspired by stories she has heard from victims during the pandemic as well as her own experience. Her plan is to disguise the app to look like others commonly found on phones such as notes or reminders. When the correct keys are pressed, it will allow women to document their abuse for legal purposes.

“Unfortunately, when women are experiencing this kind of violence, it can often leave them paralyzed and they still have to find ways of capturing evidence of what has happened to get the support they might need from law enforcement,” she says. She plans to release the app before a potential second wave and advertise it in women’s only spaces and groups to maintain a level of secrecy from abusers.

Dr. Kerrie Shaw, a family physician at Trillium Health Partners, advocates for primary care providers to continue routinely screening for IPV during virtual visits. However, there are unique challenges with asking these questions over the phone or in a video call.

“You don’t know if that person is safe or if they’re in the position to discuss things openly,” says Shaw. “(I) will always ask patients where they are and if they are in a space where they can speak safely and comfortably.”

Crosby adds that we should not just check in on patients at risk of being victims but also on patients at risk of becoming abusers. To do this, we need to ask about stress levels, conflict management and “even just tacitly list off some abusive behaviour that people might not be aware of as being abusive.”

These innovative solutions, however, are Band-Aids for gender-based domestic violence that in Canada occurs at alarming rates even outside of the pandemic, accounting for one quarter of all police-reported violent crimes.

What is needed is a preventative approach that allows for the dismantling of intersecting systems of oppression that leave women vulnerable. First, we must provide education on healthy relationships at an early age. Second, leaving an abusive partner, even during a pandemic, needs to be a real option, which means increasing affordable housing, shelter space, access to financial support and culturally relevant healthcare. Finally, prevention strategies should be focused both on potential victims and on potential abusers, reflecting a societal shift away from victim blaming.

According to Crosby, “often what we do is we place the burden on the people who are being abused to get out.” She says that any policy changes and public messaging need instead to let victims know “it’s not your fault that people are processing their anger in this way. It’s not your fault that people aren’t able to face their own trauma.”

If you or someone you know is suffering from intimate partner violence, please call 911 if you are in immediate danger and see these support services.

The comments section is closed.

Thank you for such great full information.