Canada is an aging nation – 51 per cent of our population is more than 40 years old and 18 per cent is over 65. Statistics Canada reports that in 2020, 11,517 Canadians are 100 years or older.

Although the aging of Canadians is a success, it poses unique challenges and increased demands on social, healthcare and other related services. Given our aging population, Canada should work toward becoming a model country in terms of creating a “Longevity Economy” by redrawing economic lines, changing the face of the workforce, advancing technology and innovation and, says the American Association of Retired Person, “busting perceptions of what it means to age.”

In their book The 100 Year Life: Living and Working in an Age of Longevity, Linda Gratton and Andrew Scott outline how individuals can better prepare for a longer life visit. Gratton and Scott point out that the classic three-stages model – school, work, retirement – is no longer applicable. Babies born today have a good chance of surviving to be 105. If we are to exploit longevity opportunities, we must abandon outdated notions of the traditional three-stage life.

Our communities, in collaboration with businesses and government, can seize the opportunity to support individuals throughout their multi-stage lives by working on an agenda for the decades ahead – balancing the needs of the “retirement/legacy community with emerging family populations.” This presents an interesting challenge as these groups have significant differences in their needs. How do we give attention to retirement and healthcare without sacrificing lifetime education, skill development, flexible work and transitions?

Throughout the 20th century, informed by the three-stage model, governments have primarily invested in free education and infant care. As we shift to the multi-stage model, other periods of life require similar investments and the longer we live, the greater the inequality we see in government investment. Evidence in many Canadian communities shows that re-inventing retirement requires alternative strategies such as shifting away from full-time employment to high-end consulting, starting an entrepreneurial business connected with a passion or hobby, sharing a home and other living expenses with a friend to help retirement funds go further or choosing another creative career that you love.

Increased longevity requires redefining both social and financial institutions. While we can each look forward and do our best to prepare ourselves and our families for these longer lives, the whole community must work together to “nourish, nurture and navigate” diverse initiatives.

As Canada’s population ages, the number who are frail increases. When we reach this point in our life, we need safe, relationship-centred support promoting physical and brain health, wherever we live. Investments must be made into the different types of homes for older adults.

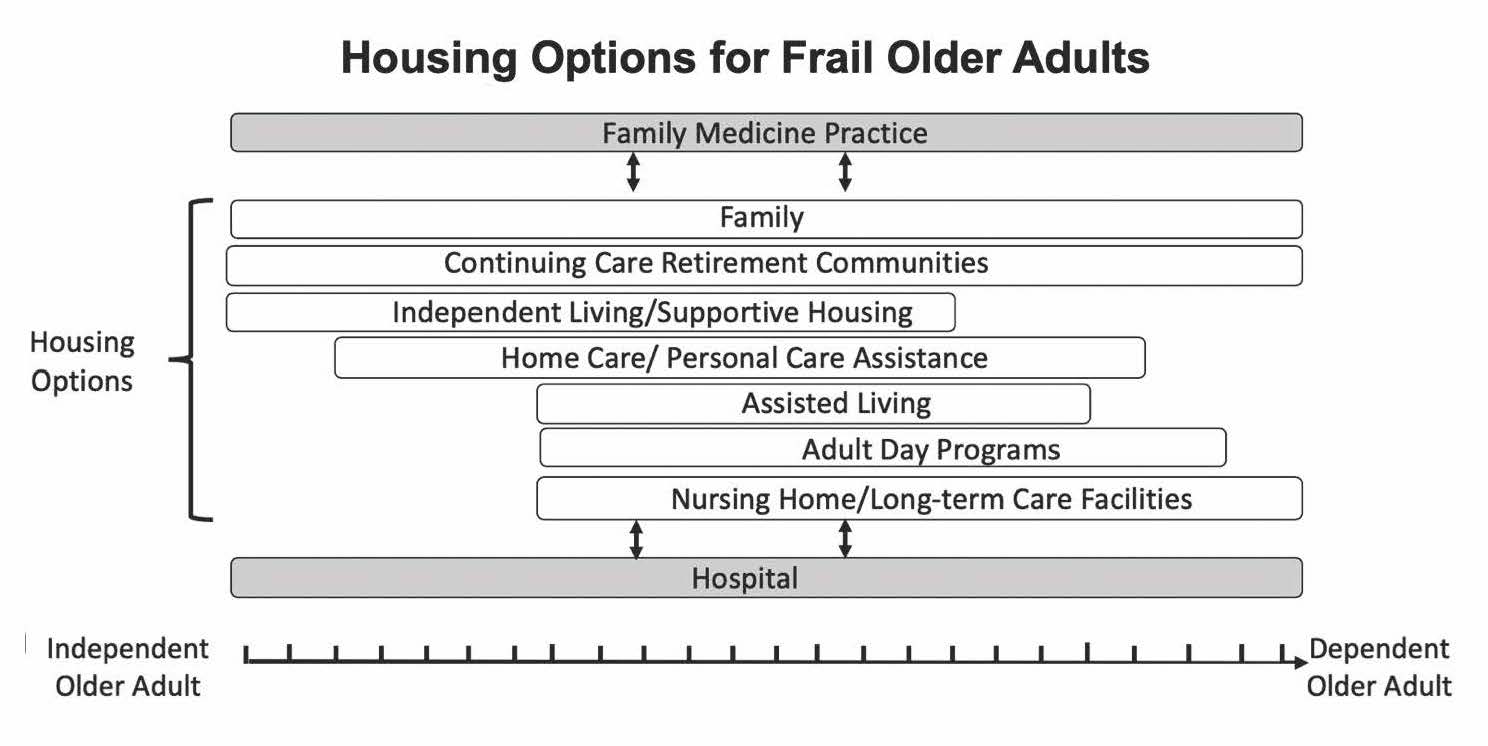

The figure below outlines types of housing, including those for people who are frail. The scale at the bottom extends from independent older adults to dependent older adults. The length of “housing” bars indicate what level of dependency along this scale is supported by each housing option. For example, at-home living with family support is a housing option that supports older adults regardless of where they are on the scale. Note the wide variety of housing options, with availability being a question in each of our communities.

The challenges of housing and providing healthcare for frail older adults go beyond living in a hospital or in a long-term care or retirement home. We cannot separate health-service provisions and social support for frail older adults. When we are frail, we have a spectrum of needs (from acute episodes to more complex, chronic conditions) and we require a spectrum of responses (from single treatments to more continuous support) where distinctions between health needs and social support needs are largely meaningless.

A variety of ways exist for enhancing availability of diverse housing options for successful aging. A comprehensive list of approaches for communities to consider is provided by Grantmaker in Aging (2019). According to this U.S. agency, the top five approaches are: 1) incentives through zoning, policy and funding; 2) building new structures; 3) policies and practices to allow people to live at home; 4) retrofitting existing homes; and 5) technology-based approaches.

The tragedy of COVID-19 deaths in long-term care homes should be an important catalyst in sparking the conversation within our communities about how they should adapt in response to changing demographics. The political and policy debate arising from the COVID-19 pandemic needs to cover redistributing government funding to account for peoples’ increasing longevity, and diversifying housing options for older adults.

The comments section is closed.

Enjoyed the read – Thank you so much. Catherine

In the early 90’s the Bob Rae government in Ontario supported new Senior Housing projects in partnership with large developers. Half the units of these buildings were market rent, half were subsidised by the Gov. and means-tested.

Toronto now appears, with Covid, to have a possible glut of new apartments, with many units small in size and perfect for seniors. Can the Ontario Premier and Mr. Tory work together with these developers to rapidly increase much needed senior housing?? It took the President of the Seniors Coalition in 1991 (full disclosure – my father) to forge this joint plan with Bob Rae. Can this be the time to do the same? John Tory found housing for the homeless in their time of need – let’s hope seniors are not far behind.

The spectrum of health and social care needs required by the aged and others, who have experienced health independence to dependence (frailty) require an integrative health care approach. Such an approach has the potential to be facilitated by the aide of technology combined with new ways of thinking and doing. But there must be a political will and accompanying financial backing to support innovative and practical policy development and implementation. Both the health and social sciences must work together to help make this change occur. The general public also have a vital role to help evoke this. Overall, no one group or entity such as a government can do this alone – it must entirely be a collective effort.

Well, I love to read about housing so thanks. The primary roadblock is we don’t have a national housing program in Canada (just a strategy). Prior to the cancellation of our national program we built 20,000 units a year of affordable housing and some of it was for seniors. We are now in a deficit of 340,000 units.