Sometimes when I reach for a bag of frozen vegetables, I’ll find a stuffed hamster in our freezer. My daughter put the disintegrating toy in a Caboodle, a clear plastic case meant for organizing makeup. There he lies, in perfect repose, on a carefully folded washcloth, like Disney’s Snow White in her glass coffin or Michael Jackson asleep in a hyperbaric oxygen chamber. She wants to keep her most prized friend, Hammie – swashbuckler, Venetian gondolier, serial entrepreneur – alive. Her father and I encourage Hammie’s periodic cryogenic sleep to kill the germs he gathers in his travels.

Although imagined relationships may not match the real thing, they may be just what children need in these periods of isolation. Imaginary friends like Hammie are a window into a child’s creative mind. They are common across cultures and can be invisible or personified objects. Older children may not talk about their companions, but they have them, too. Research shows children with imaginary friends are seldom shy, lonely or awkward but among the most sociable. These “friendships,” with all the role-playing they entail, help children to feel good about themselves, teach them about relationships and provide companionship, just like in the real world.

Tracy Gleason, a professor of psychology at Wellesley College, prefers the term imaginary companion because not all the relationships are friendships. Gleason says children with imaginary companions tend to enjoy social interaction. When they don’t have it, they invent it.

“When you have an imaginary companion, you’re inventing a relationship. And so, to some extent, you are obtaining all the benefits of that kind of relationship,” says Gleason. “A lot of kids will think about what it is like to have a friend who doesn’t want to play with them. They think about how that would feel, what they might say. It’s a safe space in which to do all of that experimentation and all that thinking because no actual relationship is on the line.”

Imaginary friendships span cultures around the world. Maureen Smith, professor of child and adolescent development at San José State University, says at the onset of the pandemic, she saw an uptick in imaginary friends among the 5- to 8-year-olds she studies. Yusuke Moriguchi, an associate professor at Kyoto University, said in an email he has also seen an increase in the prevalence of imaginary companions among Japanese children. Coping strategies could be one of the reasons.

Parents have noticed, too, and sometimes interpret an imagined friend as a sad result of isolation.

One dad in Winnipeg, posted: “We have reached the point in this garbage pandemic where I gotta push 2 swings at the park. One for my kid, and one for her imaginary friend Juanita. Cuz my kid has an imaginary friend now. Cuz she hasn’t seen another kid her age for 2.5 months. Go away Covid.”

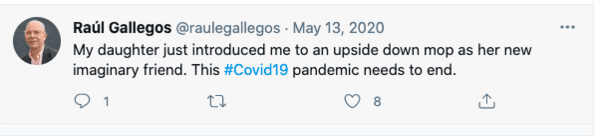

A father in Bogotá, Colombia, added: “My daughter just introduced me to an upside-down mop as her new imaginary friend. This #Covid19 pandemic needs to end.”

Some parents may discourage what they see as an unhealthy obsession once their children pass preschool age and the media often portrays strong and persistent imaginary companions as a sign of mental disturbance. Think of the boy in the 2019 Oscar-nominated movie Jojo Rabbit. His father is missing, his mother dies protesting Nazis, and his imaginary companion is Hitler. The cult movie Donnie Darko features a teenage boy with symptoms of schizophrenia who talks to a demonic rabbit. In Harvey, friends think a man is insane because his best friend is an invisible six-foot rabbit.

Imaginary friends, however, are a normal part of childhood and can hang around into adolescence. Children with imaginary friends are inquisitive and think and play in a fantastical way. Some research suggests these children often become unusually creative adults – artists and writers. The three Brontë sisters, all novelists, invented an entire imaginary world as children in the early 19th century.

Jennifer Laban, who lives in Mississauga, Ont., says her 7-year-old daughter, Mackenna, an only child, is a true people person. The start of the pandemic was difficult for her. Mackenna had never had an imaginary friend before, but a month into the pandemic, Sal appeared. Then came Zoey.

“Sal’s shy and doesn’t talk much, but she likes to ride along on people’s shoulders. Zoey’s very outgoing and chats a LOT. She’s fun and she’s Sal’s girlfriend,” Jennifer posted. The friends went to the park with Mackenna and took turns on the swings and slides.

Mackenna also missed seeing her grandfather. Cue Invisible Grandpa. He gave hugs and candy and rode a motorcycle.

“I was sad for her that she was alone, but I wasn’t sad that she had imaginary friends because they brought a lot of joy and fun into her life during that time.”

Sarah Sharp’s daughter had a few imaginary friends before the pandemic, but now she has “about 400 billion,” says the mother of the 7-year-old from their home in Oakland, Calif. The rotating circle of friends play out strong emotions. A current favourite is Rosie, her daughter’s 5-year-old ‘child.’

“Rosie was very upset because I called her the wrong name,” says Sarah.

Their family is multiracial, and last year, in the midst of protests against racism, her daughter easily discussed her friend’s skin colour as part of play.

“She’s finding her path through a really hard situation for a person who’s super social. It is allowing her to navigate relationships. She’s rehearsing what it means to interact with other people and have some sort of conflict.”

Maureen Smith says that the predominantly Latinx and Vietnamese children she studies often relate to some version of “my imaginary friend arrived when I needed her or him.”

One child she studied before the pandemic told her, “I came to America in kindergarten. I didn’t speak English and no one could speak Spanish. And my friend appeared, and she could speak both, so I could talk to her.”

Research shows that imaginary companions help children through adversities: children in foster care get emotional support and allies; young adolescents at high risk for behavioural problems experience fewer issues; teenagers form better coping strategies, are more likely to ask for help, and have higher self-esteem. And during wartime, children who care for a stuffed toy have less separation anxiety, overall anxiety and sleep problems, including nightmares.

No parent should be surprised if a child finds an imaginary friend – or 50 – during the pandemic. And the child most likely will be better for the experience.

The comments section is closed.

Aspects of this are concerning. An imaginary friend should be a bridge to help kids express their needs and feelings in a way that doesn’t make them feel vulnerable. Reading some of these situations makes me wonder if too much relience on a multitude of friends and imaginary worlds could lead to psychosis later on. A kid who is more concerned with the world and friends he invents and is hesitant to engage with his family and peers might develope anxiety disorder and phobias later on. Preferring the company of ones own made up reality might be an obstacle to making real world friendships or even getting a higher education or a stable work-life.

I love this! I had never thought about imaginary friends in this way before. This thoughtful, well researched article has changed my perspective on this topic.