In economic game theory, a zero-sum situation is one in which a participant’s gain is balanced by another’s loss. Assuming vaccine production is at maximum capacity, this is the game our world is playing: Every vaccine administered in one country is one not administered somewhere else.

Locally, the game is simple: Vaccinate as many people as possible, as quickly as possible, while targeting those most vulnerable and likely to catch the disease. This has proven challenging, however, as the vaccine rollout in Ontario has been plagued with issues regarding registration, eligibility criteria and equitable distribution.

Our desperation for vaccines is for good reason: At this point, with the virus running rampant, it is the most realistic way to bring an end to this pandemic and return to some semblance of normal life. There is evidence of this effect already in Israel.

Amidst the well-intentioned clamour for mass vaccination, however, we think it worth taking pause to reflect on some limitations of our fixation on vaccine procurement as a nation. What does it mean for global health equity? How might it hinder the global pandemic fight, and how could that in turn affect us? How might focusing too much on vaccines detract from the other measures we could be deploying to slow the spread of the virus?

The federal government’s vaccine procurement has been the target of significant criticism, in particular when vaccines were first released. At the time of writing, there seems to be a lot of frustration amongst the general public and in media that we don’t have enough vaccines, and they aren’t being delivered fast enough. Comparisons have been made to countries like the U.S. and Israel that are outpacing us and returning to normal faster than we are.

This is a common criticism being touted by our provincial government, too, which bears responsibility for vaccine distribution but is quick to pass blame for our current provincial predicament to the federal level. So much so that the provincial government is now attempting to procure its own vaccines.

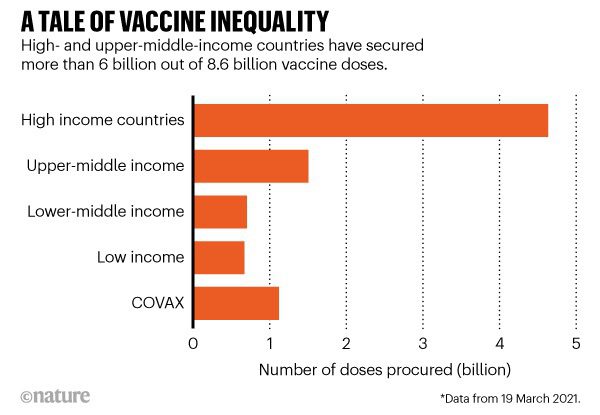

By some measures, however, Canada is actually performing adequately. Of countries that have administered more than one million vaccines doses, Canada currently ranks 10th in the world for the percentage of the population that has received at least one dose (23.2 per cent), and is outperforming the European Union (17.7 per cent) on the same metric. In contrast, some of the countries hit hardest such as Brazil (12.2 per cent), India (7.8 per cent), South Africa (0.5 per cent) are falling behind. The entire continent of Africa, which accounts for 16 per cent of the world’s population, has delivered less than 2 per cent of the world’s vaccines.

Unlike public health measures such as testing and contact tracing, our vaccine procurement comes at the detriment of others. Every low-risk, healthy 22-year-old that gets vaccinated early is an at-risk, 70-year-old who wasn’t vaccinated in a lower-income country. Case in point: As the U.S. opens vaccination to all adults over the age of 16, South Africa has only just opened its online portal to vaccinate health-care workers and adults over 60. In paying a premium to oust other countries from vaccine supply, we don’t generate more total vaccine, we just re-distribute it.

That vaccine distribution falls across pre-existing fault lines of global inequalities may not come as a surprise, but in the face of a global pandemic it is a real cause for concern.

It’s not a matter of altruism: Ensuring the pandemic ends around the world benefits us as well. Every time the virus replicates, it is an opportunity for a mutation to form – a mutation that could render the virus deadlier, more transmissible or resistant to current vaccines. There is no better example than the surge we are seeing now that is driven by variants. The longer this virus replicates unchecked, the more we risk a virus that is deadlier, more vaccine resistant and can come right back and impact us at home, even if we have been vaccinated.

It is therefore paramount that we consider the global burden of disease, not just the local one. It’s not just someone else’s problem, but ours as well.

The problem of equitable global vaccine distribution was anticipated prior to the release of vaccines. Programs such as COVAX, co-led by the World Health Organization, were designed to pool resources needed for vaccine development and production, and enable access to vaccines for lower-income countries and those without bilateral deals with manufacturers. But a number of factors, including decisions to uphold intellectual property rights, have created barriers to global vaccine production and distribution, limiting attainment of this goal. Moreover, early on it became obvious that COVAX could be exploited by high-income countries. That was the case when Canada decided to draw on the first batch of vaccines available through the COVAX supply, triggering international criticism and accusations of vaccine nationalism.

This is not to say that we shouldn’t be working hard to obtain vaccines. We must continue to vaccinate as quickly as we can, but it is crucial that we also support other countries to do the same. When Jonas Salk – the inventor of the polio vaccine – was asked who owned the patent on the polio vaccine, he responded: “The people … Could you patent the sun?” COVID-19 vaccines are too crucial for the health of the planet, too influential on humanity, to be bought and sold just like any other commodity. There is a proposal from India and South Africa to temporarily waive intellectual property rights on COVID-19 vaccines until herd immunity is reached. It is currently being considered by the World Trade Organization (WTO) and, with more than 100 countries in support, is gaining ground. Canada, however, has remained neutral.

Vaccines will help prevent another wave of virus, but it’s too late for the wave we are currently in. There are other steps we can take to control this virus at a local level that will work immediately, and in doing so contribute meaningfully to the global effort: mass and rapid testing, effective contact tracing, paid sick days and support for those most at risk – not to mention a more strategic and equitable distribution of the vaccines we already have. This is a non-zero sum, win-win strategy that will help others as well as ourselves.

As a nation, sacrificing our own needs for those of the global community is hard. Confronting these inequities and asking what we need to do differently is difficult and uncomfortable but a matter of life and death for millions around the world. We will ultimately get through this but we must do so in a way that avoids succumbing to vaccine nationalism – we can’t just outbid other countries, roll up a sleeve and wait for the curve to flatten itself. Let’s remember how the health of the world reflects the health of our own country. Let’s address our inequities locally without contributing to inequities globally.

The comments section is closed.

Edward H.C Graydon

I suppose the fact that the WHO when they decided not to endorse vaccine passports on the grounds that the vaccine in their opinion does not stop transmission nor as it been proven to actually work other than producing blood clots was a mistake as well?