Christopher King still finds it difficult to believe what happened. The grief, the pain, the reality of his passing, he says, has only partially hit him.

“I remember (what) he said before he went in,” says King, thinking back to the day his father, Alan King, underwent heart bypass surgery.

“He said he always wondered whether, before they put you under, if this is the last time he’ll see the light. And it was. He turned out to be one of the 1 per cent of cases of people that go in for this type of surgery that didn’t make it.”

Alan King, cartoonist, artist and classical pianist, was 73. He was healthy. He exercised regularly. He was on a bike ride when he first experienced chest pains and difficulty breathing.

Although COVID-19 public health safety restrictions allowed for King’s family to visit their father in hospital before and after surgery, it stripped them of one of the most important elements after his passing, says King – an in-person funeral.

“I still don’t feel like I’ve processed the whole thing,” says King. “We haven’t spent much time talking about it … I find the fact that I’m not talking about it is sort of preventing me a little bit from the grieving process. Like I’ve been at funerals for people that I haven’t known very well, or distant relatives where I couldn’t stop crying, but I don’t think I’ve cried since I stood next to my dad in the operating room.”

After the online funeral in March, King put effort into uniting his family virtually, setting up weekly game nights on Zoom. But nothing can come close to replacing what an in-person funeral would have afforded the family, says King.

“If there had been a real funeral and I had actually been in closer contact with my family, I feel like I’d be able to process this stuff,” says King. “But it’s just somewhere inside me now and I don’t even know where it is now. I just feel like I don’t know what happened. He was here and now he’s not.”

While King’s father was not one of the more than 4.2 million people worldwide who have died from the coronavirus, his death united the family with those who were forced to adapt grieving rituals in response to public health safety rules across Canada.

Christopher King, pictured with his dad, Alan King, in what has become one of Christopher’s favourite photos from his childhood. (Photo courtesy of Christopher King).

It’s not as easy as it might sound, notes Angela Sumegi, retired associate professor of humanities and religion at Carleton University. She notes that while humans have grown out of some religious and cultural rituals naturally, or by choice, those relating to death “will probably be the last things to go.”

“It’s sort of hard-wired in us to do things in that kind of holistic way … Ritual, by those that are living, kind of brings that whole person back,” says Sumegi. “It doesn’t matter who the person is or whether it is a 92-year-old grandfather or infant. The grief might be different, but the death part is not different. It’s always disturbing, it always has an uncomfortable feeling regardless.”

She notes that the pandemic has created what she calls a “second layer of loss,” whereby family and friends are stripped of the ability to say a proper goodbye; whether directly to their loved one prior to their passing or through a specific funeral or ceremony after the fact.

“There is a great sense of loss. So, you’ve lost the person you loved, but you’ve also lost the way to send them on,” says Sumegi. “You lost the farewell, and that’s a really empty feeling because it’s like if your dearest friend or child just took off, with no goodbye, no farewell, no hug.”

In Western cultures, it relates to the longing for control, says Stephen Fleming, psychology professor at Toronto’s York University. Fleming, who has authored numerous articles on grief, notes that the Western world was previously governed by the idea that life is controllable, safe and predictable.

“Suddenly, the world is not safe, the world is not predictable. In fact, it’s chaotic as hell, so that unsettles us. That’s the beginning. Then when someone dies in the middle, then the sense of being unsettled, not understanding the world, and the world not being predictable, is ratcheted up. It’s more intense,” says Fleming. “The baseline level of anxiety is heightened, and then you build loss on top of that.”

This is why humans “fall back on ritual,” he says, adding that whether culturally, spiritually or religiously based, ritual is a tool that provides familiarity, a sense of purpose and helps “restore some small measure of that loss of control.”

It can even be referred to as a “survival urge,” notes Tom Sherwood, retired minister at Orleans United Church in Ontario and retired adjunct research professor at Carleton University.

“Some religious communities are coping with it a little better and some are not,” says Sherwood.

“Spiritualities (function) to introduce a routine, a reassuring transitional routine in response to all these life-changing crises … so when there is a death, we feel we have to do the ‘right thing’… (And) social distancing is in complete contrast to any of the religious traditions.”

He explains that many religious communities have been trying to adapt and hold onto rituals in ways that still align with theologically important beliefs, bring honour to the dead and provide comfort to loved ones.

The rituals and gatherings that they would normally hold have mostly been conducted online, says Ross Paperman, funeral director at Paperman and Sons, one of the largest Jewish funeral homes in Montreal. It is an adaptation that has been less than ideal for many families.

“The thing about a Jewish funeral, and the thing about some of the people who passed away, is that these were people of a certain age or generation (for whom) tradition meant so much,” says Paperman. “The single greatest thing that you could do is to give honour to the dead because you’re doing something that can’t be returned in any physical matter.”

One of the most important Jewish funeral rituals is Shiva, a seven-day period of mourning for close relatives of the deceased. Paperman says that normally, Shiva is an “incredible thing” since it allows for everyone to come together to reminisce and move forward after loss. With COVID-19, though, families have resorted to holding Shivas through Zoom.

“A lot of people found a way because I think the human spirit is tenacious,” says Paperman. “We found a way to get as close to it as we could.”

Sometimes, though, being online is not good enough, notes Salwa Kadri, funeral director at Al Rashid Mosque in Edmonton. She says that not being able to host large in-person funerals has been a major sore point for their congregation.

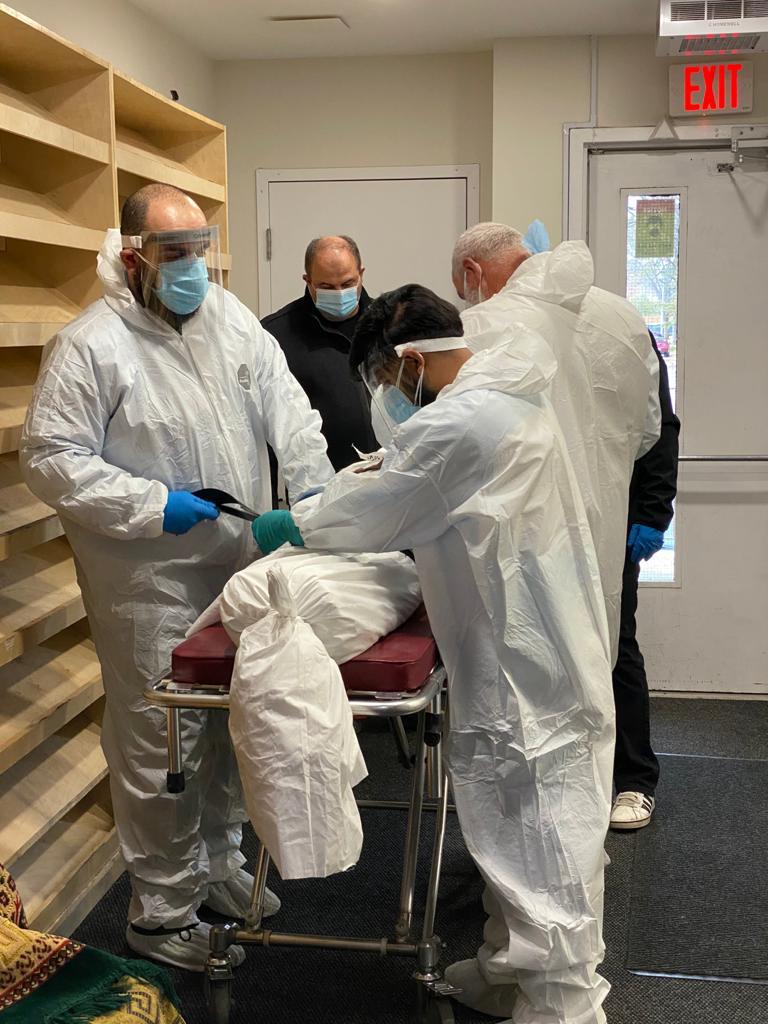

Kadri explains that their fatwa – a ruling made by local imams on issues relating to Islamic law – outlined their obligation to give full funeral rites regardless of whether the deceased was COVID-19 positive. This meant their mosque was required to perform what Kadri refers to as the “bare minimum” in the Sunni Muslim constitution.

One important element is Ṣalāt al-Janāzah– a funeral prayer offered by the congregation to seek pardon for the deceased and all dead Muslims. Kadri says the community believes that the more people attend a funeral prayer, the higher the deceased can be “elevated.” Restrictions meant her staff had to balance the community’s needs with social distancing guidelines.

Kadri reflected on one such situation a couple of months ago after a young high school student passed away in an accident. At a time when the province’s restrictions limited 10 people to a funeral, Kadri says the entire high school came, with around 60 students flooding into the centre.

“They’re all young kids … I felt really bad for them because they needed to be together. They needed to grieve, and they couldn’t go to outdoor gatherings … they weren’t allowed. And so, I opened the gym and I said, ‘This is your door, don’t come back into the centre, just stay in the gym and go out that way.’ They were in there for a good two-three hours,” says Kadri. “This was the first time many were dealing with death … They need to be with their peers, they need to talk about it.”

Al Rashid’s male burial committee, equipped in PPE, shroud and prepare the deceased to go to the burial site. (Photo courtesy of Salwa Kadri).

The move online also has been difficult for some Indigenous communities, notes Grand Council Chief Reginald Niganobe of the Anishinabek Nation. He says that normally, communities would come together for a ceremony, sacred fire, offer a cedar bath and prepare and cleanse the body of the deceased for the afterlife.

He says while some families have adjusted, even embracing online gatherings, others are holding off and still waiting to hold celebrations for loved ones who passed months ago.

“It’s very exhausting and draining on the families … It’s a mental challenge almost going through that grieving process (for) that long and I’m worried about the health effects of that,” says Reginald. “(Our) grieving process is important to go through … it’s important to be able to let those spirits move on and help them move on and help them along their journey.”

Mental health concerns have been at the forefront following the discovery of thousands of unmarked graves of children at former Canadian residential schools. Lorraine Whitman, President of the Native Women’s Association of Canada, says that many communities and families are going through another grieving or mourning period – a process that can be isolating given the nature of the pandemic. That is why the association is offering small online support circles led by elders for survivors, families and communities affected by the news and the horrors of the residential school system. Whitman says she is happy to see so many community members interested in the online formats.

“I’m quite surprised with the virtual events, of all the people that have come on and how they feel they’re in a safe space,” says Whitman. “(Because) we need to heal before we can move on. And of course, this trauma … it’s devastating, retriggering, retraumatizing our people. So healing is so important.”

The mental health effects of not processing death during the pandemic is also a concern for those who practice Jodo Shinshu Buddhism, explains Roland Ikuta, geriatric physician and member at the Buddhist Temple of Southern Alberta. He says this sect of Buddhism – with its focus on funerals, memorial services and remembrance – places importance on facing death “head on.”

“Everybody grieves in their own way, and in their own time, but you know we feel that the rituals, the services, the getting together with the rest of the family, talking about that person is all very, very important in terms of our grieving process,” says Ikuta. “Having a time to remember the person who has passed away and the contribution of that person to our lives and how they’ve influenced us is very important … If you don’t do so, it can often lead to sort of unhealthy further suffering.”

When the temple closed in March 2020, with all services moving online, the minister and sensei, Yasuo Izumi, conducted meetings and last rights over the phone, even getting special permission to visit a dying person in the hospital.

If it were not for the pandemic, Ikuta says the temple would normally have held a 49-day memorial service and follow up with a service in one, three and then seven years. He notes many of these services drew close to 500 guests prior to the pandemic.

The pandemic has highlighted that death and grieving are never “perfect,” notes Susie Henderson. Over the past year and a half, Henderson has worked as a facilitator for a number of families running online Zoom funerals.

Henderson notes that the end-of-life movement that stresses choice in medical care when nearing death sometimes makes it seem as though family and individuals have the ability to “plan the perfect death and the perfect funeral.”

“Death doesn’t happen like that,” says Henderson. “It’s kind of like when you have a birth plan and you go through all of that and you (say), hey, it didn’t happen exactly the way we planned. You have to just kind of figure it out, or deal with it, however it comes.”

She notes that although much separates faith communities in how they struggled over the past year dealing with grief and loss in different ways, one thing has united everyone – the fact that we are all “in the same boat.”

Henderson held the Zoom funeral for King’s family after their father’s passing.

Although Christopher King says the online format may have robbed the family of an important experience, he says it still allowed him to connect to people in his dad’s life that he previously never had the chance of meeting.

“I heard stories from people that I hadn’t heard before,” says King. “(It gave me a) new perspective on dad, on his life, and it sort of enriched my memory, a little bit, of him and helped me process his passing a little better.”

King and his half-sister, Chloe King, also had a chance to speak during the service – something that he says afforded him the opportunity to talk, address and express some of his sadness to those closest to him.

“It was the only time I’ve really expressed any grief about the passing of my father at all,” says King. “I expressed some of the grief and some of the, you know, different feelings that I had growing up with dad.

“I did struggle a bit with what to say but I definitely had the chance to say everything I wanted to … and I felt like I needed to do that.”

The comments section is closed.

My sister, who was living in a nursing home, died just weeks into the pandemic, so I can certainly relate to the need to ritualize the death and/or celebrate the life of a loved one and not being able to do so in a timely way or at all. Whether or not funerals, memorials or celebrations of life in any way assist the spirits / souls of the deceased to “cross over” I don’t know. But I am quite certain that a proper sendoff not only honours the dead, but it can and does help many of the living to gather themselves and carry on with their lives. My family and I have not yet had the opportunity to say a proper goodbye to my sister, which has only perpetuated my grief and saddled me with the feeling of an unfinished task.

Thanks for the piece.