“You have to die a little to live,” my friend’s husband told me as I began chemo last summer. He’d had Stage 2 cancer, like me, and was preparing me for how difficult the treatments would be. And he was right: In fact, it was hard to get my feet to walk through the hospital doors for my treatments. I knew that this was my best shot but on some visceral level I really wished I didn’t have to do it.

I shared updates about my cancer treatments with my friends on Facebook and it helped to get encouragement. But something else also happened on my timeline: Facebook’s advertising algorithms began targeting me for cancer ads from scammers selling phony treatments. These companies promised that I could cure my cancer “naturally without toxic chemotherapy or surgery” using vitamin IV therapy that allegedly had “the same mechanism as chemotherapy.” A page called Breast Cancer Conqueror offered a host of custom supplements and another clinic in Mexico offered beachside IV cocktails that would defeat cancer with “antioxidant properties.” It all sounded good – too good to be true.

I reported the ads to Facebook in the hope the platform would remove them (it didn’t). I also wrote about it, joining the legion of voices raising the alarm about mis- and disinformation on social media.

A year later, not much has changed on Facebook. While the mega-corporation has made promises to try to contain false news about COVID, it remains a massive problem on the platform, along with fake news on cancer. Although the Center for Countering Digital Hate (CCDH) identified 12 health disinformation “superspreader” accounts on Facebook in March, 59 per cent of the content still had not been removed by July. The CCDH’s reporting led U.S President Joe Biden to call out Facebook in July, stating to media that health misinformation on the platform was “killing people.”

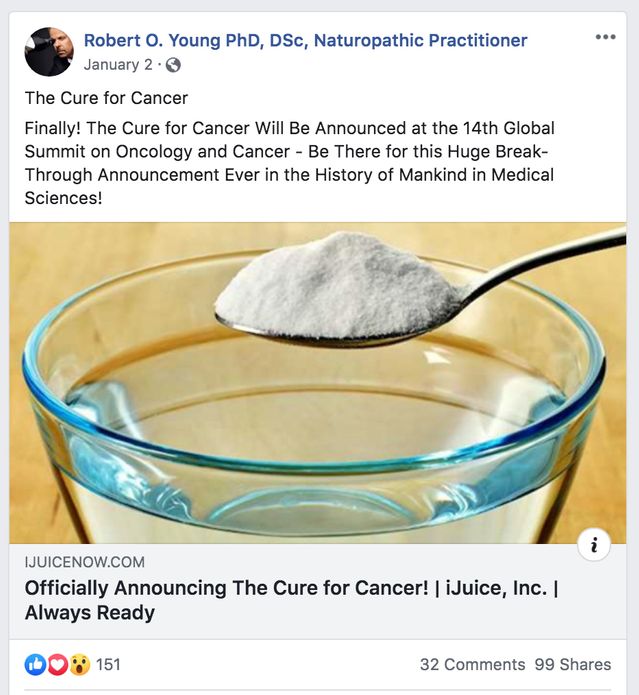

Image of cancer cure claim posted on Facebook. Source: Twitter

In the Wild West of health misinformation on social media, hope kills. In a large study of 1.6 million patients with non-metastatic breast or colorectal cancer, patients were nearly five times more likely to die if they used an alternative therapy rather than a conventional treatment.

A July 2021 report headed by the Huntsman Cancer Institute outlined that one third of the most popular cancer treatment articles on social media contained misinformation, the majority of it promoting harmful approaches to care. The study also showed that articles containing misinformation got more clicks and engagement than science-based content.

In a 2020 report, Professors Tamar Wilton and Avery Holden studied nearly 800 Pinterest posts that made factual claims about breast cancer, finding that more than 50 per cent contained misinformation, including phony cures such as colloidal silver, dandelions and green tea and/or downplaying the role of mammograms in detecting cancer. A review by NBC in December 2019 found that much of the most viral health misinformation was about cancer, citing headlines such as “Ginger is 10,000x more effective at killing cancer than chemo” that generated more than 800,000 engagements. The Wall Street Journal has reported on social media cancer scams, including millions of views of YouTube videos claiming cancer can be cured by black salve, a highly corrosive product described as “dangerous and life-threatening” by the U.S. Food and Drug administration.

While regulators have cracked down on false claims that vitamin C IV therapy prevents COVID infections, marketers continue to promote it as a breast cancer cure even though some studies show that it impedes the effectiveness of common chemotherapy agents (such as doxorubicin and cisplatin) from 30 to 70 per cent. Vitamin C infusions can also have a negative effect on longer-term breast cancer drugs; a 2014 study showed that vitamin C “antagonized the cytotoxic effects of Tamoxifen,” making the drug less effective and acting as a “pro-oxidant” that counteracted the benefits of Tamoxifen.

To many, it’s counter-intuitive to think that a vitamin could complicate cancer care. It’s hard to accept that harm can be done to us in a painless procedure or that something painful can actually help us heal. To wit: the healthy choice that keeps us alive doesn’t always feel healthier. Fake cancer cures are often marketed as “natural” and “simple” by websites such as Natural News – and the temptation is real. You can walk into an alternative cancer centre with leather armchairs and skylights, write your big cheque and get a round of applause for your vitamin C injections … or you can schlep down the hospital hallway for AC chemo followed by (checks notes) crying and puking. Some of the best ways to fight cancer also wreak havoc on the body; this fact makes it easier for pseudoscience marketers to draw patients in with the illusion of comfort and control.

Several years before I was diagnosed, an acquaintance developed cancer. She declined a common life-saving surgery and headed on a journey into the world of vitamin IV therapy, mineral supplements and so-called “shamans,” traveling to South America in a quest-like search for the truth about cancer. One of the last times I spoke to her (shortly after I was diagnosed), she said she’d been told cancer comes from our own past traumas that we’ve pushed down inside ourselves. “We can’t heal from cancer until we heal from the emotional pain inside us,” she told me. From her perspective, it was an act of kindness to give me this advice. She thought she was helping me cure my cancer.

But in the five years since she’d declined surgery, her cancer had progressed. Soon, it was beyond the point of no return. As I was finishing up my radiation treatments and getting my energy levels back, she passed away at home with hospice care.

We must hold cancer scammers – and the platforms that enable them – accountable. But we also must help people realign their perspectives on disease so they can’t be persuaded by fake solutions.

To build a counteroffensive against the false comfort of pseudoscience, we need new narratives about the difficult aspects of our care. If the charlatans can frame their so-called treatments around anecdotes and fairy tales, our hospitals can surely create more compelling narratives that reflect our lives, leveraging the social media sphere to beat the scammers at their own game.

The science is clear: We can’t cure cancer with turmeric tea, faith healers, positive vibes or vitamin infusions with ocean views. The inconvenient truth is we have to struggle and fight for our best chance at life.

The comments section is closed.