Just before Lloyd Douglas arrived in the northern Ontario municipality of Sioux Lookout, he was ready to quit medicine.

Born and raised in Jamaica, Douglas knew he wanted to be a doctor when he read the book Gifted Hands; he realized public health was his passion while studying medicine at the University of West Indies. After moving his family to Canada, he could not get a residency training position and had to find work in other areas of health care.

“I worked as a ward assistant and as a housekeeper. I learned to appreciate the other aspects of hospital care. I cleaned gurneys in the ER and ORs after a C-section,” he says. “It was both rewarding and grounding.”

Despite multiple previous rejections, his wife persuaded him to continue applying for a residency spot, focusing on his intention to serve First Nations communities in preventive medicine and public health. Finally, after four years of trying, he got his spot. Northern Indigenous communities have been a focus of his career ever since.

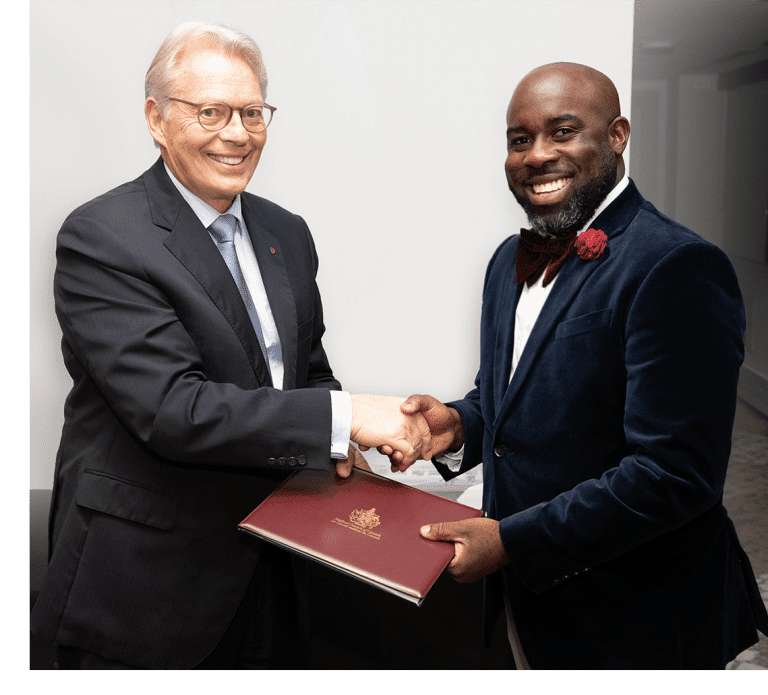

Douglas pictured winning the Dr. Ian Bowmer Award for Leadership in Social Accountability. Photo via the Medical Council of Canada.

Douglas says he connected with the population in part because of past atrocities they had suffered and the generational trauma they have had to endure – in part, because of a shared background of colonization.

Douglas first heard about the coronavirus while working as a physician consultant with the Independent First Nations Alliance, building relationships and working alongside the five First Nations within the alliance. His team knew how vulnerable First Nation communities would be if the virus reached Canada and had to act quickly.

“We started hearing about what was happening in China at the end of 2019 and realized we had to do something to serve these communities,” says Douglas. “In January 2020, we visited each one and went through their pandemic plans.”

“I worked as a ward assistant and as a housekeeper. I learned to appreciate the other aspects of hospital care.”

Shortly afterward, Douglas started working with the Sioux Lookout First Nations Health Authority (SLFNHA) as the planning section lead for the COVID-19 Regional Response Team (CRRT) under Incident Commander Natalie Bocking and later under John Guilfoyle, both public health physicians. Last April, Douglas assumed the Incident Command role for the SLFNHA’s CRRT. The health authority is responsible for creating and administering health programs and services for the 33 First Nations communities in the area.

At the start of the pandemic, SLFNHA quickly realized there was no coordinated response plan for the region. “Most public health agencies have an emergency response plan they can activate so everyone starts working together – primary care providers, law enforcement, churches, businesses, etcetera. But in our region, we had neither the regional response plan nor sufficient resources,” Douglas recalls. “Initially, we had to find our way in the dark. I remember Dr. Natalie Bocking saying, ‘It’s like we were trying to fly the plane while we were still building it.’”

The SLFNHA CRRT built pandemic-response infrastructure mostly from scratch and ensured local chiefs and other key stakeholders were involved from the start. It also had to fill major gaps in remote Indigenous communities that the pandemic laid bare. When it comes to public health oversight, the Sioux Lookout region is split between two distinct public health units. Health services including some primary care is provided by Indigenous Services Canada, which covers mainly primary care and nursing. The region is also geographically vast – for example, Fort Severn First Nation is 700 kilometres north of Sioux Lookout. This made contact tracing exceptionally challenging.

In 2010, mandated by the regional chiefs, SLFNHA developed its own integrated model for public health for the communities it serves, called Approaches to Community Wellbeing (ACW). ACW is rooted in cultural knowledge and Anishinaabe teaching and is an alternative model of a public health unit designed by Indigenous people for Indigenous people.

Pre-COVID, the ACW was planning to take responsibility for the management of communicable diseases across the region. When COVID struck, ACW was given responsibility for case management and contact tracing, but does not have public health recognition under the Health Protection and Promotion Act, meaning it could not issue or enforce a communicable disease order.

“We were given the responsibility, but not all the tools,” says Douglas. “We could not do the public health work from beginning to end. For example, if a person refused to quarantine or isolate, a medical officer from the local public health unit would need to be looped in and briefed to take any action.

“Being on the ground, I really understood from the very first case in our region the amount of work it would take to keep these communities safe.”

Sioux Lookout Meno Ya Win Health Centre. Photo courtesy of the Ontario Centre for Innovation.

One highlight was the partnership with First Nation communities to set up facilities using existing infrastructure, like schools, to help individuals from multi-generational, overcrowded homes safely isolate. “When you were hearing about the big cities, you know, renting out entire hotels for quarantine or whatever, we were doing that from day one,” says Douglas.

Another achievement the SLFNHA CRRT is proud of is supporting the development of pandemic teams in each community to help execute public health initiatives. These local teams are activated by a chief once a positive case is identified.

“When families are isolating, they need food, they need support. And community teams rallied together to provide that,” Douglas says. “To assist teams in contact tracing; to assist providers who fly in and don’t know the language; we couldn’t have done this without the communities.”

Douglas credits the teams for keeping the number of cases across the First Nations in Sioux Lookout to just over 200.

“We were given the responsibility, but not all the tools.”

“Our region was one of the first to implement First Nation community point-of-care-testing programs with help from Paul Sandstrom and Adrienne Meyers from the National Microbiology Laboratory and then colleagues from Ontario Health North and the Ministry of Health,” he says. “Helping remote First Nation communities implement point-of-care-testing programs greatly reduced the waiting time for COVID results. Initially, it could take more than two weeks to get a COVID test result for some remote First Nation communities.”

Douglas sees no reason why ACW should not be recognized provincially as a public health department for the Sioux Lookout region.

According to Douglas, while the intention to give First Nations communities control over their own health care is laudable in concept, the starkly disproportionate infrastructure and resources result in massive inequities.

“Based on our COVID-19 experience, we have proven that ACW – in the midst of the worst public health crisis in our lifetime – works. ACW is ready to officially assume some public health responsibilities in the region, especially the management of communicable diseases,” he says. “This is my call to action.”

Douglas has put down roots in Sioux Lookout and made it home for his family. Despite being thousands of kilometres away, it reminds him of his native Jamaica.

“I’m a country boy at heart,” says Douglas. “I fit in well in Sioux Lookout. Apart from the cold and the snow, a tree is a tree or a bush is a bush wherever you go.”

The comments section is closed.

I think it is interesting about Sioux Lookout also being colonized. Because now we are an independent country and our flag is our own. No matter where or how long you are here the rights we share equally.