We are only beginning to understand the impact of the pandemic on patients with cancer, from diagnosis to treatments and end-of-life care.

Kelly Walker, an elementary school teacher in Toronto, had a stem cell transplant in February 2020 as part of her cancer treatments. She was released from hospital weeks later to isolate at home and was soon joined by nearly everyone else in the city as COVID-19 restrictions took hold. Since then, Kelly’s experience of cancer care has been deeply impacted by the pandemic, influenced by waves of community transmission, stresses on our health system and the public health decisions of our governments.

Kelly, who has myelodysplastic syndrome, a form of blood cancer, told me she felt “very fortunate to be supported,” throughout her on-going chemotherapy. “Not every cancer patient has that and those are the people I worry about,” she said.

The words fortunate and lucky often come up as Kelly and I discuss our cancer treatments. Although we were both able to receive our diagnoses and care on time, we live with the grim knowledge that Canada’s over-burdened health system has not been able to meet the needs of all cancer patients.

In fact, our country may be on the brink of a second epidemic – a cascade of cancers that went undetected for the past two years as patients were unable to seek the primary care they would normally receive.

It was early in the course of the pandemic that projections began emerging around the concept of “deaths secondary to COVID,” a term to describe people who died from cancer or other diseases that could have been cured if the pandemic had not stressed health systems. Risk factors for secondary loss include delayed cancer detection; delays in surgery or other treatments; and poor management of treatment side effects.

Focusing on early diagnosis of breast, colorectal, esophageal and lung cancers, a group of U.K. researchers estimated that diagnostic delays would lead to nearly 4,000 deaths within five years there. In a 2020 research review in the BMJ, the researchers estimated, conservatively, that a surgical delay of 12 weeks for all patients with breast cancer for one year would lead to 1,400 excess deaths in the U.K. and 700 in Canada.

Alex Broom and colleagues warned in a November 2020 editorial in Clinical Cancer Research that “little emphasis has been placed on the … consequences of COVID-19 for how cancer care (itself) is delivered.”

Information is now coming in about secondary deaths and pandemic-related stage migration, where an undetected cancer becomes more severe due to lack of diagnosis or care. In May, Ontario’s Science Advisory Table reported a more than 12 per cent increase in deaths in Canada, a number exceeding the number of deaths directly related to COVID: “The subsequent increase in mortality due to non-COVID-19 causes could reflect the impact of delays in care for conditions other than COVID-19, including cancer.” In Spain, a retrospective study of lung cancer diagnosis found 38 per cent fewer lung cancer cases were diagnosed during the pandemic, with patients seeking initial care with more advanced stages of cancer. A study of 799,496 patients in the U.S. found a 29.8 per cent decline of new diagnoses for eight types of cancer in the first wave, with a 19.1 per cent decrease in diagnoses in the third wave.

As data has trickled in, so have anecdotal accounts – and they are alarming. Sheila Singh, a pediatric neurosurgeon at McMaster Children’s Hospital in Hamilton recently spoke to the CBC about an uptick of advanced cancers in children at her hospital due to delays in diagnosis. “I feel like I’ve been practicing in a Third World country,” she said. “I have seen disease that has spread so far that it’s almost like cases I’ve read about in rural India. It’s been quite difficult and alarming.”

Singh’s experience reflects that of several Toronto-based ER doctors.

“Anecdotally, it seems as though we are seeing more cancers being diagnosed in the emergency department,” Keerat Grewal, an emergency physician at Sinai Health and research fellow at the Schwartz/Reisman Emergency Medicine Institute, told me. “Not only do we think we may see this with cancer, but other conditions such as heart disease and stroke.”

She noted a report in the Canadian Medical Association Journal showing that the cancer screening backlog continued to increase even up until December 2020.

“We know that delays often result in worse outcomes for patients,” Grewal said. “We need to ensure that the backlog of screening and delays are addressed and that we plan appropriately for future cancer care.”

In some cases, patients did not choose to avoid care; they had no access to it. In Ontario, primary care clinics had significant leeway in scheduling in-person appointments; many clinics chose to be closed for routine physicals and well-child visits. This left some patients who have chronic conditions (like asthma and diabetes) without in-person care for 18 months or longer. Patients receiving virtual care for symptoms that would normally be addressed by their primary care team were at times referred to the ER.

Other times, diseases (including cancer) were undetected in virtual appointments. Singh gave the example that there is often a visible sign (macrencephaly) of brain tumour in children. But, she pointed out, it can go undetected in a virtual visit, “whereas if that child walked into a room, it’d be the first thing you’d notice about them.”

The Canadian Cancer Society has been keeping track of gaps in care through four patient/caregiver surveys since July 2020, averaging 1,073 respondents per survey. Its overview as of November 2021 found that 23 per cent of patients reported delays in receiving their diagnosis (a 5 per cent increase from pre-COVID), with 34 per cent reporting barriers impacting their diagnoses in general. Nineteen per cent reported delays between diagnosis and treatment during the pandemic – up 5 per cent from pre-COVID times.

According to Diego Mena Martínez, VP of strategic initiatives at CCS, the charity’s helpline and peer-to-peer support groups now have more members with late-stages cancer and the CCS has even created new groups that were “not necessary before COVID” to accommodate the shifting demographics.

He noted that the message of “stay home, be safe, protect the health-care system” may have had a deterrent effect, where some patients did not seek care with early cancer signs. The message was important, he told me, “but it had an effect on (whether patients were) going to the doctor.”

At the same time, some provincial governments were sending out different messages, with a cascade of optimistic openings, then closures, then re-openings in what felt like an endless cycle of false hopes and crushing failures. Prior to the vaccine rollout, each re-opening signaled a further narrowing of the social worlds for cancer patients as friends and family ventured into high-risk situations – and out of our lives.

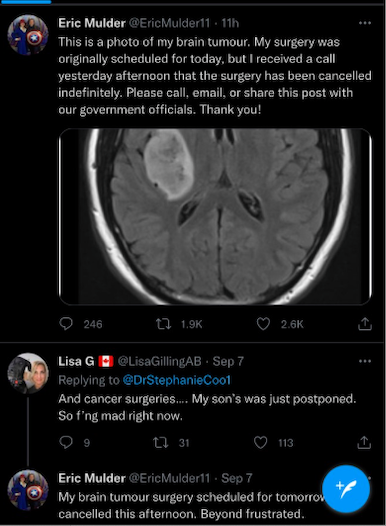

Alberta recently offered a stark visualization of the realities of being a cancer patient during a pandemic– in the wake of the provincial government’s “Open for Summer” initiative, cancer surgeries were canceled as overburdened hospitals dealt with a pandemic of the unvaccinated. Some Alberta cancer patients took to social media to express their grief. On Sept. 7, Eric Mulder tweeted a medical-imaging photo of his brain tumour, writing: “My surgery was originally scheduled for today, but I received a call yesterday that the surgery was canceled indefinitely … Beyond frustrated.”

Like health-care workers, we as patients have experienced ongoing frustration and a slow-burn of anger. Vaccines have been a miracle, but the crisis in health care is far from over. If trends continue, oncology will increasingly be marked by late- and end-stage disease. There is also a backlog of care to be provided. For example, Ontario is behind by 15.9 million medical procedures, some related to cancer diagnoses and treatment.

The immediate future of health care will likely be defined by the appearance of illnesses that flourished among the forgotten, patients who were inadvertently neglected in the strategic plans of the pandemic years. Secondary loss will be a significant presence – one we should not become inured to, but rather learn from as we plan for the next crisis.

“Moving forward,” asks Mena Martínez, “how can we rethink the system?”

The comments section is closed.