[su_dropcap style=”simple” size=”5″]N[/su_dropcap]urses have been at the forefront of caring in this pandemic. Many are burnt out, almost all are exhausted – and a frightening number of mid-career and senior nurses are leaving or considering leaving the profession. And an exodus of nurses means losing clinical expertise in patient care.

Ontario, with the lowest registered nurse per capita ratio in Canada, already has felt some of the impact of this exodus as hospitals close areas or provide hallway care. And the situation will get worse – in a survey conducted by the Registered Nurses of Ontario, 15.6 per cent of nurses said they anticipated leaving the profession within the next year. Bill 124, which limits annual salary increases to one per cent among other things, is one of many reasons but the problem is more than just about wages. It’s about an ongoing lack of recognition of nurses’ efforts in upholding health systems – often at their own expense. The health-care system will need to look deeper into what’s making the people who support it sick to save itself from further collapse.

A typical day of nursing includes assessing clinical concerns, monitoring symptoms, checking vital signs, checking for bed sores, helping change patients, priming IV lines, giving medications and updating families about care plans. In other words, nurses are the glue that holds a unit or a team together, especially through these stressful times.

We spoke to nurses working in Ontario to learn about the little extras they do to keep themselves motivated and connected with patients and colleagues.

[su_dropcap style=”simple” size=”5″]R[/su_dropcap]oxie Danielson works in a family health team in Toronto. While the core part of her job is being in the clinic Monday to Friday, the people she sees face structural barriers to care so she also spends her free time advocating for them and doing outreach work.

She says that “not only is my job to do the hands-on care with my clients, but it’s also to protect the community at large” outside the nine to five job. Roxie is part of the Street Nurses Network, a group working with people experiencing homelessness. Early in the pandemic, she and other nurses set up a phone line for people in encampments to call and have a nurse be dispatched.

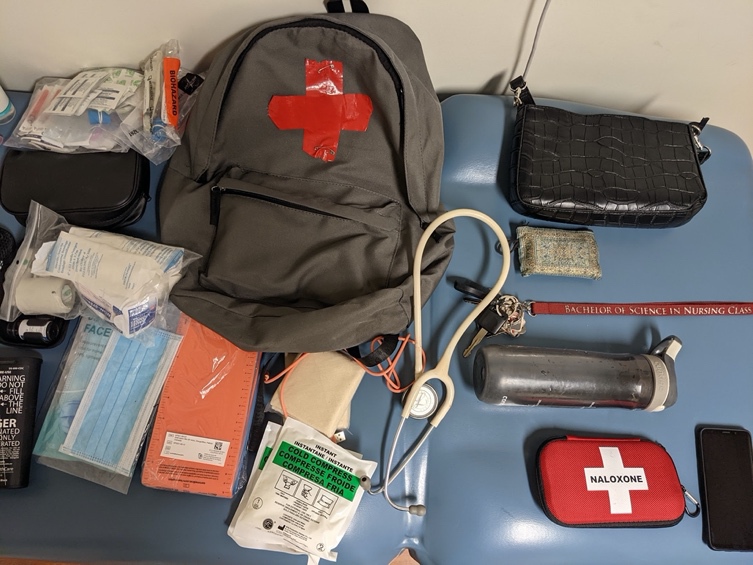

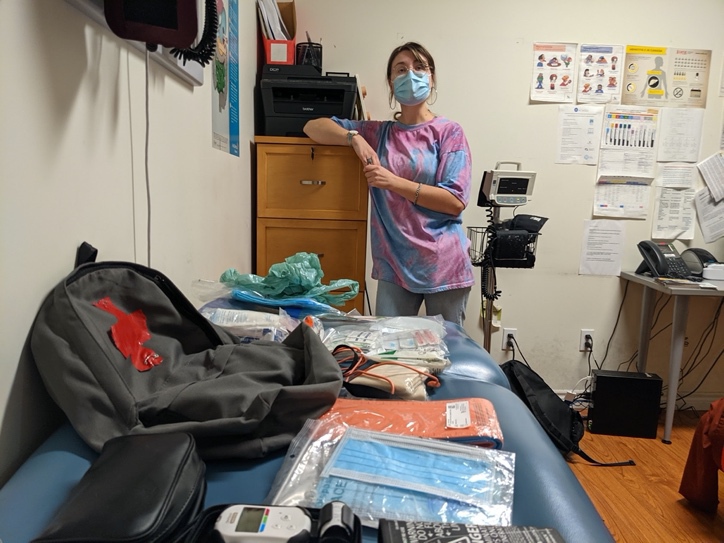

Using her experience in outreach work, Roxie has put together a backpack that she carries around with wound care supplies, harm reduction kits and granola bars. She says it’s important for “your clients to see that you’re standing up for them.”

She says she feels bad for her nursing colleagues in hospital settings because of how much work has been given to them. She says she has been privileged to be in a clinic that’s been supportive of her work, adding that she hasn’t had to work overtime like hospital nurses and that it has been painful to see what they have been going through during the pandemic.

Roxie says nurses are often told not to speak up and “we usually get reprimanded when we do.” She says she is happy that “we are seeing more nurses speak out and band together.” She says her advocacy work has helped her feel less isolated and get through COVID.

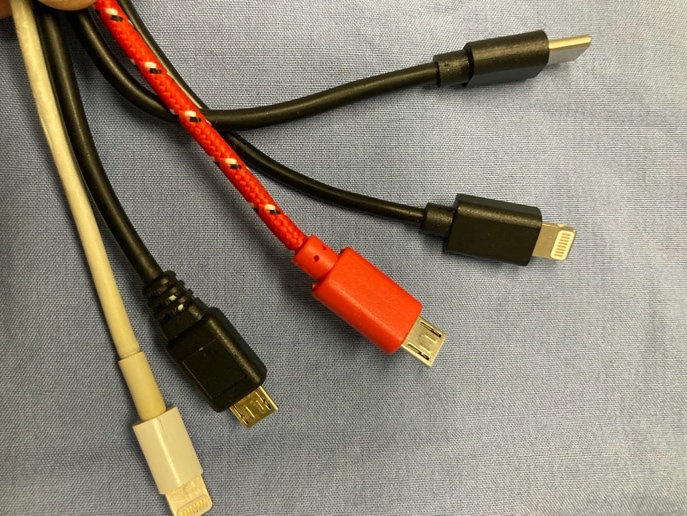

[su_dropcap style=”simple” size=”5″]P[/su_dropcap]eople around the emergency department know to ask Zoe, an ER nurse in Central Ontario 18 years into her career, when they need a phone charger. An incident years ago made a lasting impression: When her mom ended up in the ER, Zoe realized her cell phone’s battery was at 10 per cent battery and she didn’t have her phone charger with her. Someone lent Zoe a charger and “that small little piece was huge because then I could let my dad know what was happening.”

Zoe says she’s “had lots of different cell phones over the last 10 years. So, I’ve just kept the chargers and I keep them in my bag. And people know to come to me when they need a charger.” She says she has one for iPhones and many for the different Android phones. “It’s just a small thing, but it’s been especially helpful with COVID when family members can’t visit. The patients are always thankful, and the chargers always find their way back to me.”

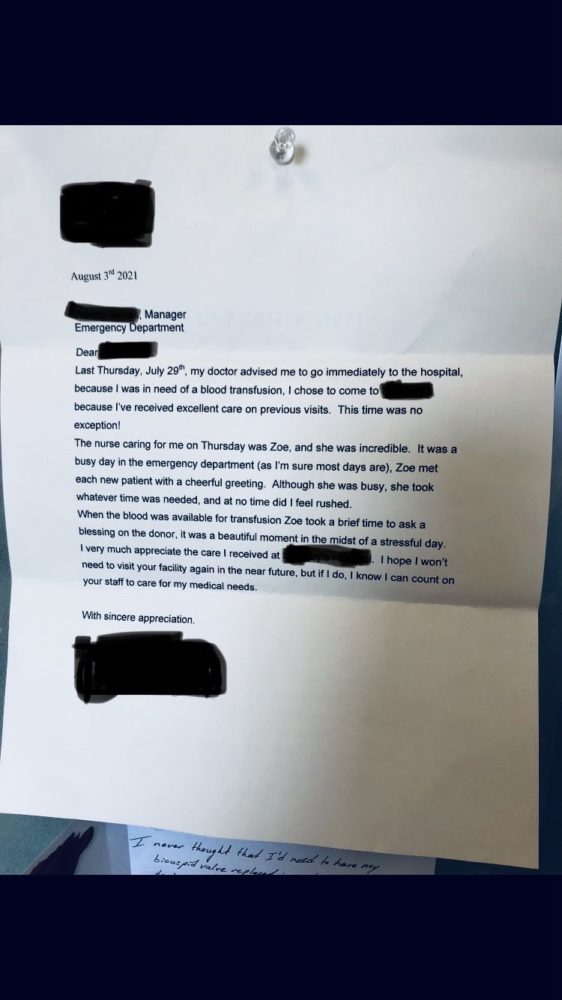

Another extra step Zoe takes is specifically recognizing blood donors “because it’s huge for a patient to receive a blood transfusion.”

She usually tells the patient, “Somebody has donated this blood to you. I’m just going to – we’re just going to – take a moment to say thank you, and we appreciate them taking the time out of their day to offer their donation. And here it is for you right now.”

Zoe is fearful about senior nurses leaving the profession: “It’s a feeling of loss.” One of the senior nurses of 18 years in Zoe’s department had just left the week before we spoke, leaving her as one of the most senior nurses. She says the department is just “coming to terms with it and knowing we don’t have that person to turn to and say, ‘Hey, what would you do in this situation? Or what do you think we should do about this?’”

She explains that it’s the sticky situations that scare her when losing that senior experience – “Like, if we don’t have a nurse who can triage today, or we don’t have a nurse who can do resuscitation today, what are we going to do?”

[su_dropcap style=”simple” size=”5″]L[/su_dropcap]aura, a mid-career emergency room nurse in Toronto, says, “I happen to drink a lot of coffee. I think a lot of us do in this job because the caffeine helps get us through.” She adds that it’s “unfortunately not without consequences for me because I end up with really, really bad reflux.”

Laura is someone people know to go to when they need to do self-care in the middle of a shift. She says “we treat ourselves so that we can continue to do our job and continue to provide care. I think that we’ve been doing that for a really long time. But the feeling of that happening now is more at the forefront than I’ve ever felt.”

She brings Pepcid with her every day so if she can’t take a break and needs “to sip coffee here and there, so that I have the energy to continue to move forward, and to keep things going,” she “ends up treating myself along the way.”

She also brings Tylenol and Advil with her. She says, “If you haven’t had a chance to drink enough water and you get dehydrated and you get a headache or whatever, you have different ways to keep going.”

Laura, who frequently takes the role of charge nurse in the ER, says, “You do need to look after yourself but at the same time, it’s hard to do that if you feel like your colleagues haven’t had a chance to do that.”

She says she likes working in a dynamic, fast-paced work environment. “That’s what we feel passionate about, and that’s what drives us.” But it’s “also hard when you don’t feel like you’re making a dent or an impact because you’re just stretched so thin.”

I spoke to Laura on a Monday evening shift, often the busiest shift of the ER in any given week. She and two other senior nurses were switching each other off, between the team lead role and triage, because they were six nurses short that evening.

Laura has made the difficult decision to leave the ER for a job on another unit where she can gain more skills.

She says many pressures of the job existed before the pandemic, but health-care staff also feel demoralized because of the attention paid to the unvaccinated or those who harass health-care workers. “We’ve gone from health-care heroes to health-care zeroes in some elements of the public view and it’s hard to balance and be able to do your job every day.”

“There comes a point in nursing, and in the hospital system and everything else, that there’s only so much that you can do. And for me personally, there’s only so much that I can bear witness to day in and day out without feeling like it’s draining me and taking away my joy.”

She says because nursing is an essential profession, nurses don’t have the bargaining power that other professions may have. Part of it she says is also “because we are a female-dominated profession” and taken for granted. She says Bill 124 feels “like a little bit of a slap in the face. We’ve been the backbone of trying to get the entire province through this pandemic and looking after people at our own peril sometimes – like not taking a break or having to drink massive amounts of coffee and getting heartburn.

“But you can’t help but wonder how much of an impact that is having on where things are going.”

[su_dropcap style=”simple” size=”5″]S[/su_dropcap]ue, a nurse in Toronto, initially started working in the community but for the past few years has been working as a float nurse to help fill staffing gaps in medical and surgical units. She can be on a cardiology inpatient ward one shift and a neurosurgery floor the very next.

Sue says she loves being kept on her toes. She usually works night shifts and explains that nighttime coverage at a hospital is often very different from the daytime, with fewer nursing staff, doctors or allied health-care staff around.

Though she works with different teams of nurses and patients regularly, she finds ways to build connections and community. She keeps Tim Hortons or Starbucks gift cards with her and often treats colleagues to coffee in the morning after a night shift. She says after a long night shift, when you’re tired and often feeling underappreciated, having a little treat to look forward to can be a pick-me-up.

Sue also keeps a supply of treats like granola bars, gum and snacks, that she shares with colleagues and patients when they need a break. She covered the COVID unit at her hospital frequently during the height of the outbreaks and says because many patients couldn’t leave their room or go anywhere, she’d “bring them a little bit of something to brighten their day … a coffee or snacks, or little treats from the local pharmacy. A little something.”

Sue says the influx of newer nurses replacing those leaving the profession can present challenges when dealing with complicated situations and with higher patient loads. On a recent shift, Sue was on a unit with one charge nurse, two new graduate nurses with less than three months of experience, and herself. She says everyone, including the nurses with little experience, is expected to take on eight patients because of shortages and ongoing challenges: “The strain and burden can get overwhelming, and it becomes a safety issue.”

She knows that people get “called health-care heroes all the time. But we’re also human. We’re not martyrs and we need a break as well.”

[su_dropcap style=”simple” size=”5″]M[/su_dropcap]elissa works in a trauma unit in Toronto, taking care of people who have been seriously injured. Many patients in the unit are there for months, often dealing with spinal cord injuries or multiple broken bones. When people complete their hospital stay, she and other nurses coordinate with other services including physiotherapy and occupational and speech therapy to celebrate milestones in a patient’s recovery.

Team members keep pom-poms, streamers and balloons in their lockers. When long-term patients finally are transitioned to rehab, the team lines up and parades the patients through the hallway.

This a generic photograph of a patient parade and not a photograph of Melissa or the hospital where she works.

I spoke to Melissa on a Saturday afternoon when the team was three nurses short, with no hope of replacements. The work was non-stop as patients were admitted to her floor from the overcrowded emergency room while the team was also trying to help offload the ICU.

Melissa says it’s the patients that we work with that keep most of us coming back. But, she adds, the times look bleak; everyone’s feeling so burned out that at times it feels hopeless. She says she can understand why some feel like “this is it and I need to change.” Melissa says people on her unit are “not just looking for money in our pockets directly right now. We want support.”

The comments section is closed.

Well written and another bit of insight into what our nurses go through and the extra care over and above. Loved this article, Thank You.