First in a series of articles exploring the results of the OurCare survey.

Family medicine is the front door of the health-care system. But for too many people in Canada, that front door is now closed.

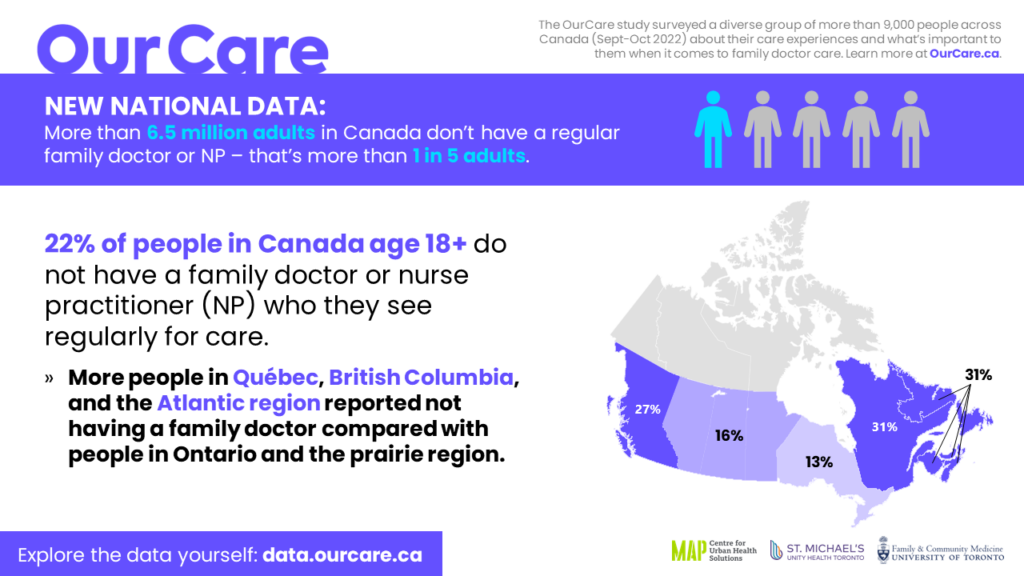

Results from the OurCare national survey estimate that more than one in five Canadian adults – 6.5 million people – do not have a family physician (FP) or nurse practitioner (NP) they can see regularly for care, a situation that has become worse during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The survey was conducted between September and October last year and includes more than 9,000 responses from across the country. It’s the first phase of OurCare, a national initiative to engage the public on the future of primary care in Canada.

We found that the situation is particularly bleak in some parts of the country. In British Columbia, Quebec and the Atlantic provinces, approximately 30 per cent – almost one in three adults – reported not having a family doctor or nurse practitioner. Contrast that to 13 per cent in Ontario.

And some groups are worse off than others. Fewer adults who were racialized, lower income and in poorer health reported having a family doctor or nurse practitioner.

Thirty-five per cent of those age 18 to 29 said they didn’t have a family doctor. Some young adults may not think they need one. Indeed, 17 per cent of respondents who were without a family doctor or nurse practitioner said they weren’t looking for one, most commonly because they thought they were healthy and didn’t need one. Yet, as family doctors, we know the importance of being connected to primary care early in people’s lives.

At first glance, the numbers don’t seem as bad for older adults. But it’s a huge concern that 13 per cent of those 65 and older reported not having a family doctor – everyone in that age group needs access to primary care.

Primary care – the type of care provided by family doctors and nurse practitioners – is foundational to any well-functioning health system. Family practices are the first place you should turn when you have a new health concern. They manage ongoing health conditions and provide care to keep you well in the first place. They are the entry point into the health-care system, coordinating the care you get from others, including specialists. Without it, patients are lost and left alone to navigate a complex system.

So, where do they turn?

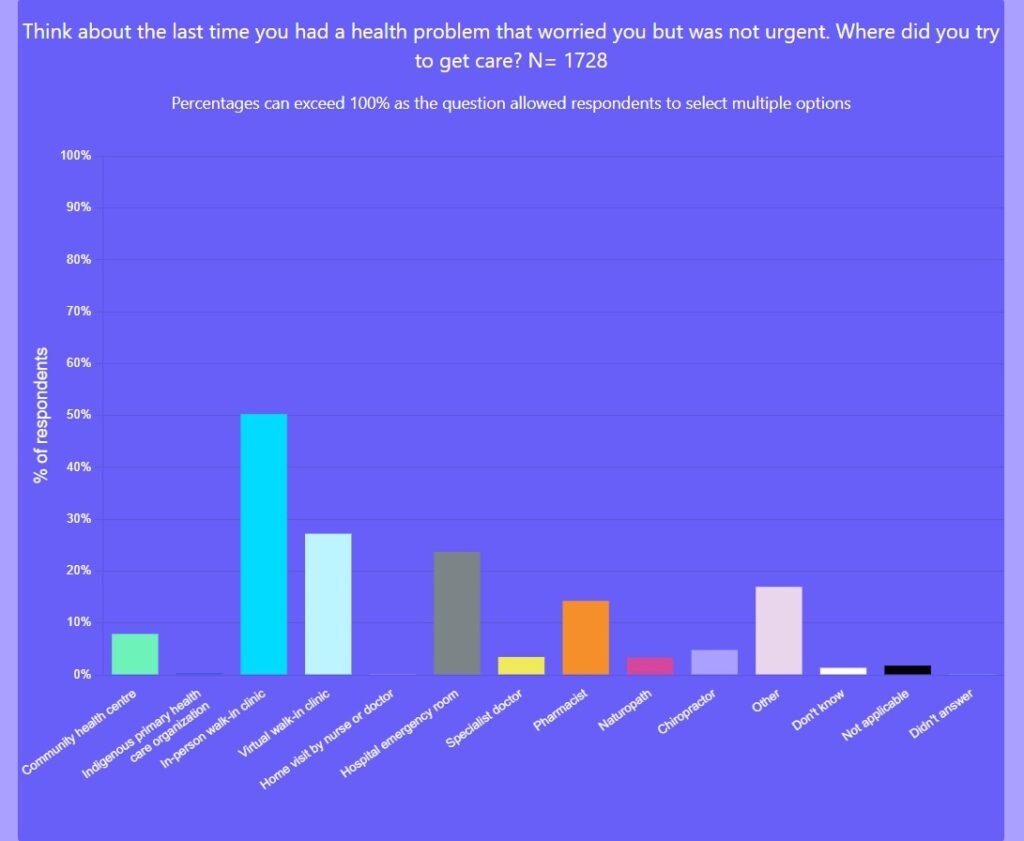

About 12 per cent of respondents who did not have a family doctor or nurse practitioner said they had another regular provider they turned to – most often a specialist physician or pharmacist. The last time these adults had a health problem that worried them but was not urgent, most reported turning to an in-person walk-in clinic, virtual walk-in clinic or hospital emergency room. Some also turned to pharmacists, chiropractors, naturopaths, specialists and other providers.

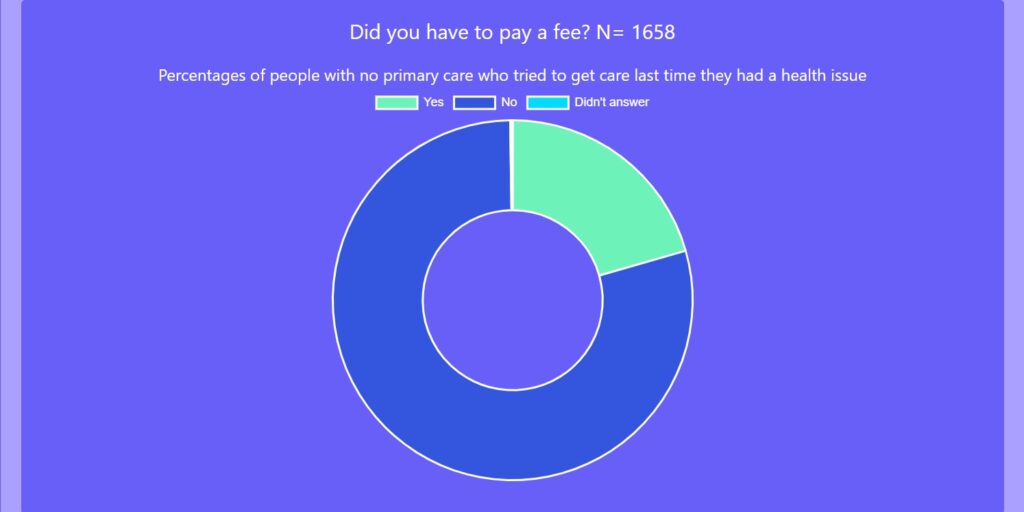

Too often, care had a price.

Twenty-one per cent of those without a family doctor or nurse practitioner reported they had to pay a fee when they sought care for their urgent problem; 80 per cent of the time that fee was for the appointment itself. The percentage of those reporting they had to pay a fee was more than twice as high in Quebec than other provinces.

We need to understand the circumstances in which people are being charged for care. Some survey respondents may have been charged a fee for seeing health professionals whose services are not publicly covered, but recent reports raise concern that some may be charged for primary-care services that ostensibly should be covered under the Canada Health Act.

Canadians have been clear time and time again that access to health care should be based on need and not ability to pay. Yet, the most basic health-care service, primary care, is now inaccessible to many – and it’s concerning that for some, access to any kind of substitutive care requires paying out of pocket. We need urgent investigation to understand the scope of the problem.

Just as in other parts of the health-care system, the pandemic has made a bad situation worse. In 2019, Statistics Canada estimated 4.5 million people age 12 and over did not have a regular health-care provider. Our results suggest a dramatic increase in the percentage without a family doctor or nurse practitioner in just three years.

Our findings are in keeping with a recent analysis of health administrative data in Ontario that found the number of people without regular access to primary care rose from 1.8 million in March 2020 to 2.2 million in March 2022. It also aligns with our research showing an increase in the proportion of family doctors stopping work in the first six months of the pandemic; our 2021 survey of Toronto-area doctors that found one in five were thinking of closing their practice in the next five years.

Health systems with strong primary care have better outcomes, better equity and lower costs. Federal funding directed toward primary care is a great step in the right direction. Ultimately, provincial governments need to use the money wisely to address the crisis in access and ensure that everyone who wants a family doctor or nurse practitioner can get one – without having to pay privately.

Explore the data yourself at data.ourcare.ca. For more information about OurCare, visit OurCare.ca.

The comments section is closed.

In principal, all people should have a doctor in Canada, but we need to recognize that many choose not to be attached because they feel docs aren’t helpful. Many people choose to go to walkin clinics so their ailments can be treated while they are actively sick. So many docs just monitor illness, without treating it when called for, or just ignore problematic symptoms. Eg., my husband’s heart condition and glaucoma were finally diagnosed by a sleep doctor not his family physician.

Great, I am skin specialist I mean dermatologist and had one year fellowship from China, if you need me can come to Canada to help Canadian people.