Preventing injury is a public health concern: According to the 2021 Cost of Injury in Canada report, injury kills more people ages 1 to 44 years than any other cause.

Despite this burden and the impact on the Canadian economy through increased health-care costs and losses in labour – as well as indirect costs in the form of pain, suffering and diminished health and wellbeing to individuals and their families – injury prevention remains inadequately resourced at the local, provincial, territorial and national levels.

Upstream interventions to prevent injury or disease have been effective throughout history. In 1854, John Snow traced the source of cholera in London, England, to a drinking pump and removed the handle to prevent further transmission. In recent times, masks, handwashing, physical distancing and vaccines have prevented or reduced the transmission of COVID-19.

From a public health perspective, preventing something from happening is a better option than attempting to fix it once it has happened, right?

Not only does prevention avoid unnecessary financial expenses to the health-care system, it also saves human costs. The effects of these costs stretch beyond individuals to their families, workplaces and communities, and often have ongoing impacts over decades, creating financial burdens and changes in health and mental health.

Injuries from road crashes, falls among older adults and children, poisonings, drownings, intimate partner violence and sports participation, to name a few, negatively impact people’s lives and compromises the health and wellness of Canadians. However, there are evidence-based interventions that have shown significant results in preventing injuries, for example changes to road systems to slow cars, making it safer for people who walk, cycle and/or wheel.

So, why aren’t we seeing the widespread or faster implementation of these interventions in all Canadian cities? If there is evidence to show the positive influence of these interventions, what’s the hold up?

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, injury prevention was largely under-resourced across public health strategic planning. Given what we know about the burden of injury in Canada, and confirmation from the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) about the importance of injury prevention for public health, why does injury prevention remain an under-supported and under-recognized area of public health work?

One problem is that the public is not aware of injury as a significant public health issue, while another problem is that most folks don’t consider themselves at risk for injury – “it won’t happen to me!” When information about the large injury burden is shared, it is usually followed by questions like “why am I not aware of this?” which begs the question: why is injury prevention absent from the public health agenda?

A fundamental challenge to gaining support is the indirect costs of injury and the need for cross-sectoral solutions. For example, while costs are borne in the health sector (e.g., emergency department visits, hospital admissions) the most effective solutions require work in other sectors (e.g., from transportation, speed reduction and road design). Due to government levels and silos, the costs of an effective solution in one area (e.g., transportation) are not seen or given credit for the resulting savings that occur in the health sector.

Further, at the local level, public health professionals active in injury prevention are often responsible for a huge portfolio, including chronic disease and substance use. They often don’t have the resources, human or financial, to dedicate to injury prevention. This is concerning, given the scope of preventable injuries across multiple settings that require the work of professionals in a variety of sectors: transportation, education, health and non-profit/non-governmental organizations.

More importantly, injury-prevention efforts require the expertise of public health professionals who are often left out of important conversations. For example, public health professionals are often not at the table when a municipality is discussing road-safety initiatives to decrease traffic-related injury and death. To be effective, these decisions must be informed using a Safe Systems Approach that relies on cross-sectoral collaboration. In addition, public health can provide important data that can inform decisions.

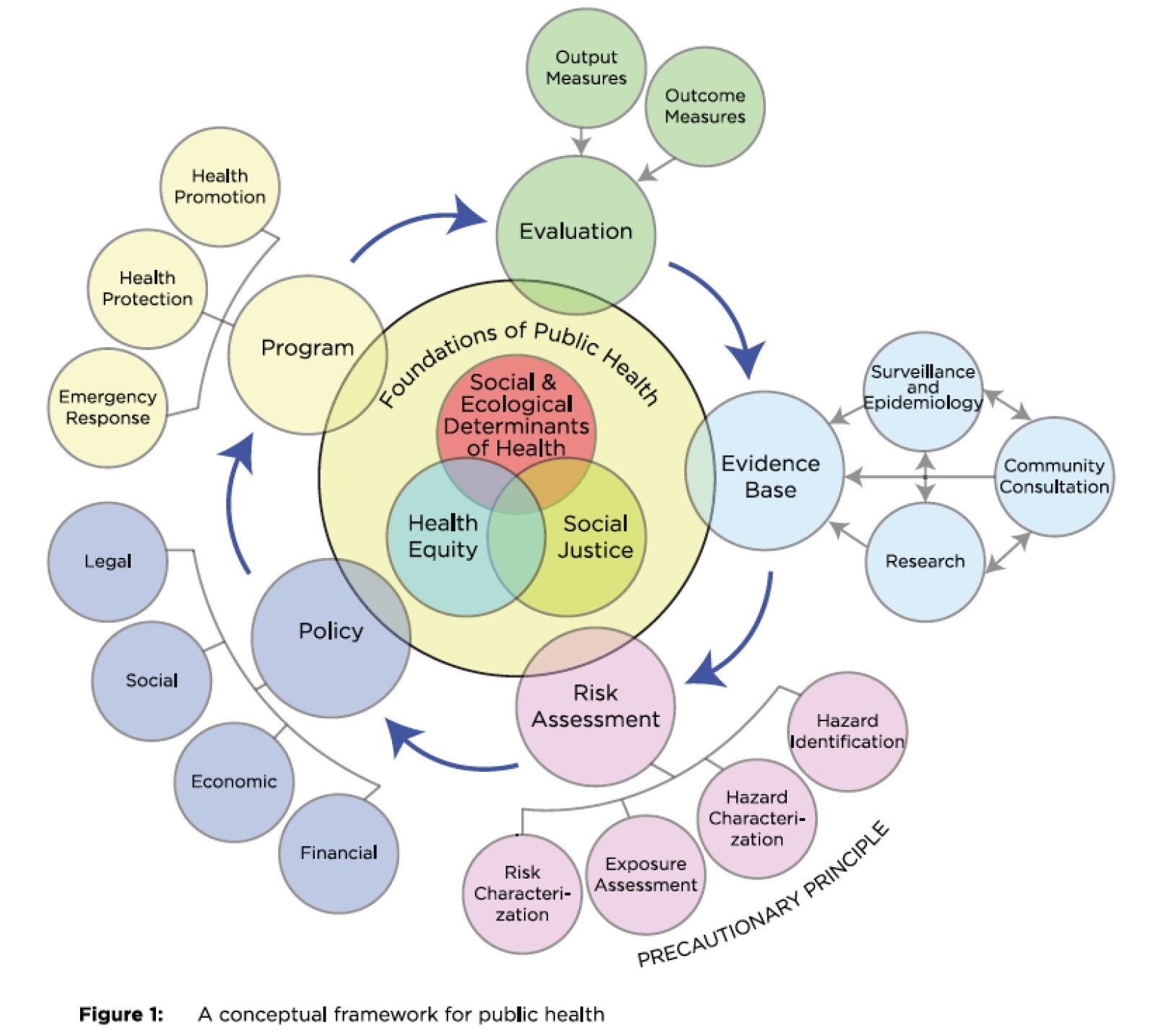

One solution is to increase funding and resources to enhance public health professionals’ capacities and connections with other organizations and sectors. Public health professionals bring a wealth of valuable expertise and data about the local context that is essential for upstream solutions to prevent injuries. Public health experts across sectors bring foundational approaches on how to address issues, such as the Public Health Approach (Fig. 1). This approach centres health equity, social justice and social determinants of health concerns when developing and evaluating public health programs and policies.

Source: Canadian Public Health Association

Public health experts can demonstrate what happens when prevention is not achieved, and they have proven successes that demonstrate the strengths of these approaches. Most of us are aware that seat-belt use reduced deaths and injuries. After legislation required children to be in car seats, the deaths and injuries sustained by children in collisions significantly declined. However, data showed deaths and injuries continued for children who should have been using booster seats; education campaigns alone were not enough to convince parents to use these for their children. Seat belts, alone, were not fitting these children properly, resulting in devastating soft-tissue injuries. Provincial and territorial efforts resulted in the adoption of booster-seat legislation in the majority of Canadian jurisdictions.

But what happens when we do succeed and reduce health-care costs as injuries reduce? If there are fewer patients from fewer road crashes, for example, the resources freed up should be reinvested in both the health-care sector to address other health-care needs and into injury prevention programming to further reduce injury rates, further lessening the burden on our health-care system and on people’s lives.

Despite the lack of resources and support, there are exceptions that show what can be achieved with investment and accountability. For example, British Columbia has made a concerted effort to prioritize injury prevention in its public health activities, such as B.C.’s Vision Zero in Road Safety for Vulnerable Road Users Grant Program that offers accessible microgrants for small infrastructure projects designed to address road-safety concerns in small, rural, remote and Indigenous communities. The British Columbia Injury Research and Prevention Unit (BCIRPU), in partnership with the Ministry of Health and Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure, is a driver for this work. BCIRPU describes itself as “a leader in the production and transfer of injury prevention knowledge, supporting the integration of prevention practice into the daily lives of British Columbians.”

Overall, the lack of injury prevention prioritization across the Canadian health system is of great concern – people in Canada are needlessly dying and being seriously injured. We already have solutions that are effective, prevent death and serious injury and are evidence informed. Can you imagine having the cure for cancer and not making it available? Of course not. But that is the reality when trying to get support to implement solutions that prevent injuries.

If we are truly invested in improving the health and wellness of Canadians, we must dedicate more public health resources to preventing injury instead of responding to it after the fact.

The comments section is closed.

The editorial authored by Dr. Barry Pless, a renowned leader in the field of injury prevention, twenty-five years ago, shed light on an apparent dual approach taken by society and policymakers regarding the prevention of diseases compared to the prevention of injuries. It discusses the case of hepatitis C infection and contrasts it with injury prevention measures, particularly focusing on the issue of speeding in school zones and residential neighborhoods.

Dr. Pless’s interesting observations from his thought-provoking editorial:

Selective Compensation for Diseases: The editorial points out that the government decided to compensate Canadians infected with hepatitis C after 1986 because a proven method of screening was available after that date. This implies that the government acknowledged a responsibility to act once a preventive technique became feasible.

Lack of Parallel in Injury Prevention: The author argues that while diseases like hepatitis C receive attention and action when preventable measures are available, the same level of responsibility and action isn’t usually seen in the context of injury prevention. The “double standard” in this context refers to the differing levels of attention, accountability, and action taken in disease prevention compared to injury prevention, despite both having a significant impact on public health.

Injury Prevention Challenges: The editorial suggests that injuries are not commonly treated as diseases in many countries. As a result, principles of disease prevention are often not applied when addressing similar injury prevention challenges. Injuries, unlike diseases, don’t seem to carry the same level of urgency for policy intervention.

Comparing Disease and Injury Prevention: The editorial draws a parallel between disease prevention (screening for hepatitis C) and injury prevention (enforcing speed limits in school zones). Dr Pless argues that the logic behind compensating disease victims for a government’s failure to apply known preventive measures should also apply to injuries caused by known risks, such as speeding.

Data and Logic: Dr. Pless presents data that supports the importance of enforcing speed limits. The reduction in speed has a significant impact on the injury rate. The editorial suggests that if the logic behind disease prevention compensation is applied, victims of injuries caused by speeding should also be entitled to compensation due to the failure to apply known injury prevention measures.

Potential Reasons for Inaction: The author speculates about reasons why the argument for injury prevention compensation hasn’t gained traction. These reasons include victims blaming themselves or perceiving injuries as accidents beyond prevention.

Final Thought: The editorial concludes by leaving readers with “food for thought” regarding the disconnect between disease prevention and injury prevention and why the same principles of government responsibility aren’t applied consistently across both areas.

Dr. Pless rightly concluded that the perceived discrepancy between how disease prevention and injury prevention are approached by policymakers and society. It emphasizes the need for a more consistent and comprehensive approach to preventing injuries and suggests that the same principles of responsibility and compensation should apply in both contexts.

REFERENCE: Pless IB. A double standard? Disease v injury. Injury Prevention: Journal of the International Society for Child and Adolescent Injury Prevention. 1998 Sep;4(3):165. DOI: 10.1136/ip.4.3.165. PMID: 9788082; PMCID: PMC1730397.