France Légaré, Canada Research Chair in Shared Decision-Making and Knowledge Mobilization, wants to have stimulating conversations and be able to move around with her dog until she dies.

Danielle Martin, the Chair of the Department of Family and Community Medicine at Women’s College Hospital, wants to “smell chocolate until I die.”

The two doctors are among the 200+ who took the time to fill in the blank on a whiteboard, “I WANT TO__ UNTIL I DIE,” an initiative I undertook after tuning in to a hospice and palliative care medicine Twitter chat in the good old days of Twitter.

As a layperson who became an entrepreneur in the health space, I was intrigued by the lament of health-care professionals on the chat: If only people talked about end-of-life wishes more, much grief could be avoided.

I bit: What’s there to talk about besides Revive or Do Not Revive (DNR)?

One of the main things these good folks advocated for is completing paperwork – an advance directive _ to ensure end-of-life wishes are met in the event you can’t speak for yourself. But with research showing that the more paperwork is completed, the more potentially burdensome interventions are indicated, why not flip the script and ask what people actually want right until the end? What small, feasible pleasure, joy, comfort will make life meaningful till the end?

I wasn’t sure how my approach was going to sit with health-care professionals, so I decided to bring my fill-in-the-blank whiteboard to the various health conferences I attended as a patient partner.

The first board was completed by Alex Jadad, founder of eHealth Innovation: “I want hugs until I die.” Sandy Buchman, former President Canadian Medical Association, had a simple thought: “I want to keep on caring until I die.” Health journalist André Picard: “I want to run until I die.” And ethicist Ross Upshur: “I want to continue my Hegelian approach for hairstyling until I die” (Ross is bald).

It was gratifying to see such uptake, plus the smiles while tackling thoughts of death. Having said that, often I had to re-direct answers: “This isn’t a bucket-list question. It’s not what you aspire to do; it’s a small joy, pleasure, comfort that you want until the end.”

The theme that most came through was feeling purposeful. Reading, writing, creating, being in service to others.

Another had to do with senses: Where doc Danielle wants to smell chocolate, many want to eat, to hear the ocean, birds, be with nature.

Knowing what someone wants in their life can be a blessing for caregivers, says Colleen Young, Online Community Director at the Mayo Clinic. “My mother’s asked me to make sure to massage her legs if she can’t speak for herself. She’s given me something to do at a time when I might feel useless and helpless”

Same with my 104-year-old father-in-law: “I want my hearing aids in until I die.”

Advance Directives and Advance Care Planning (neither term is widely used by the general public) are about determining, and putting in writing, what you don’t want in the way of invasive interventions at life’s end. But research shows that Advance Directives do not ensure medical treatment lines up with patients’ wishes at end of life. Nor do they improve quality of life. Among the reasons for this gap is confusing or vague language that is easily misinterpreted. Indeed, the term most of us who are not health-care professionals know best is the Living Will administered by a substitute decision-maker.

Whether Living Will or Advance Directive, there are problems with the concept.

How can you know in advance what you do or don’t want? How can you anticipate all the what-ifs? As Michelle Howard, an associate professor at McMaster University with expertise in palliative care, puts it: ‘You’re a different person at life’s end than when you completed that paperwork’.

Then there’s the practical issue of where is that document when it’s needed? Does your substitute decision-maker know the job you’ve assigned them? Are they comfortable potentially going to bat for you – possibly against wishes of others in your caring circle. There are countless stories of the daughter/son/relative who parachutes in with different ideas about what to do. And what about the health team – do their responsibilities and legalities preclude honouring wishes?

Flipping the script on Advance Care Planning doesn’t mean I don’t agree with it: I believe any thought put toward life’s end is useful. What my approach has done for me is to take note of what makes up a “good day” and try to incorporate as many as possible.

My own fill in the blank: “I want to pat dogs until I die.”

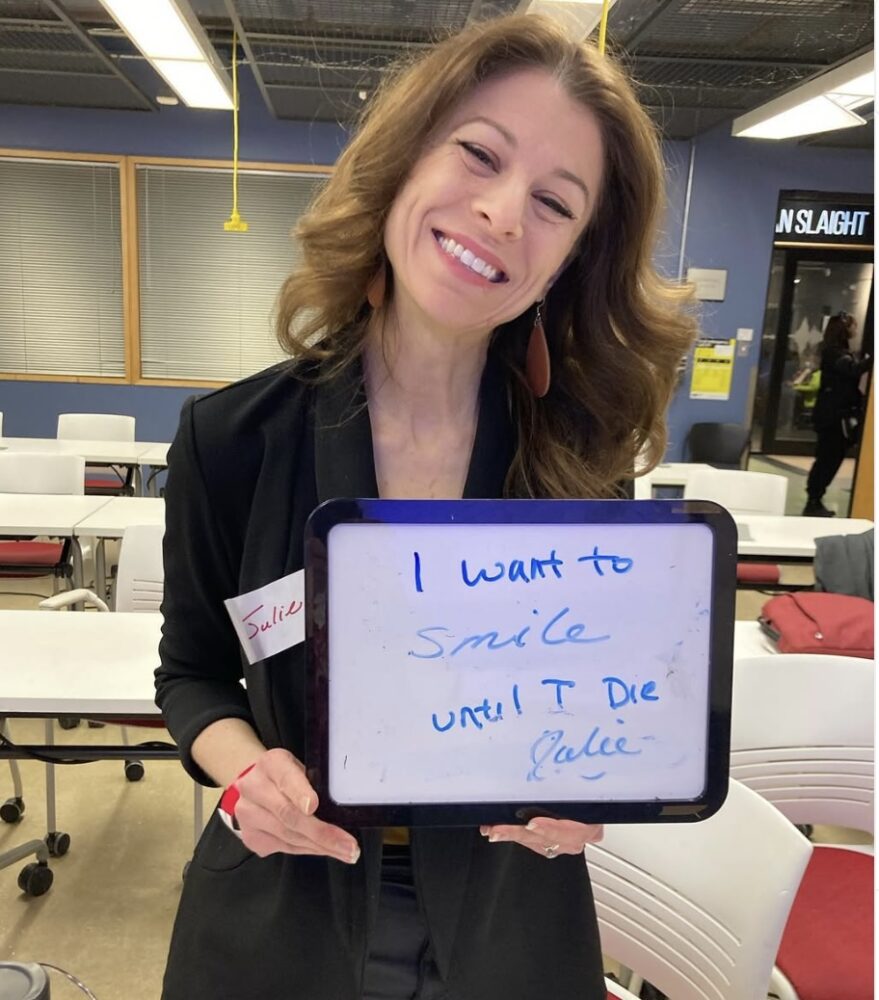

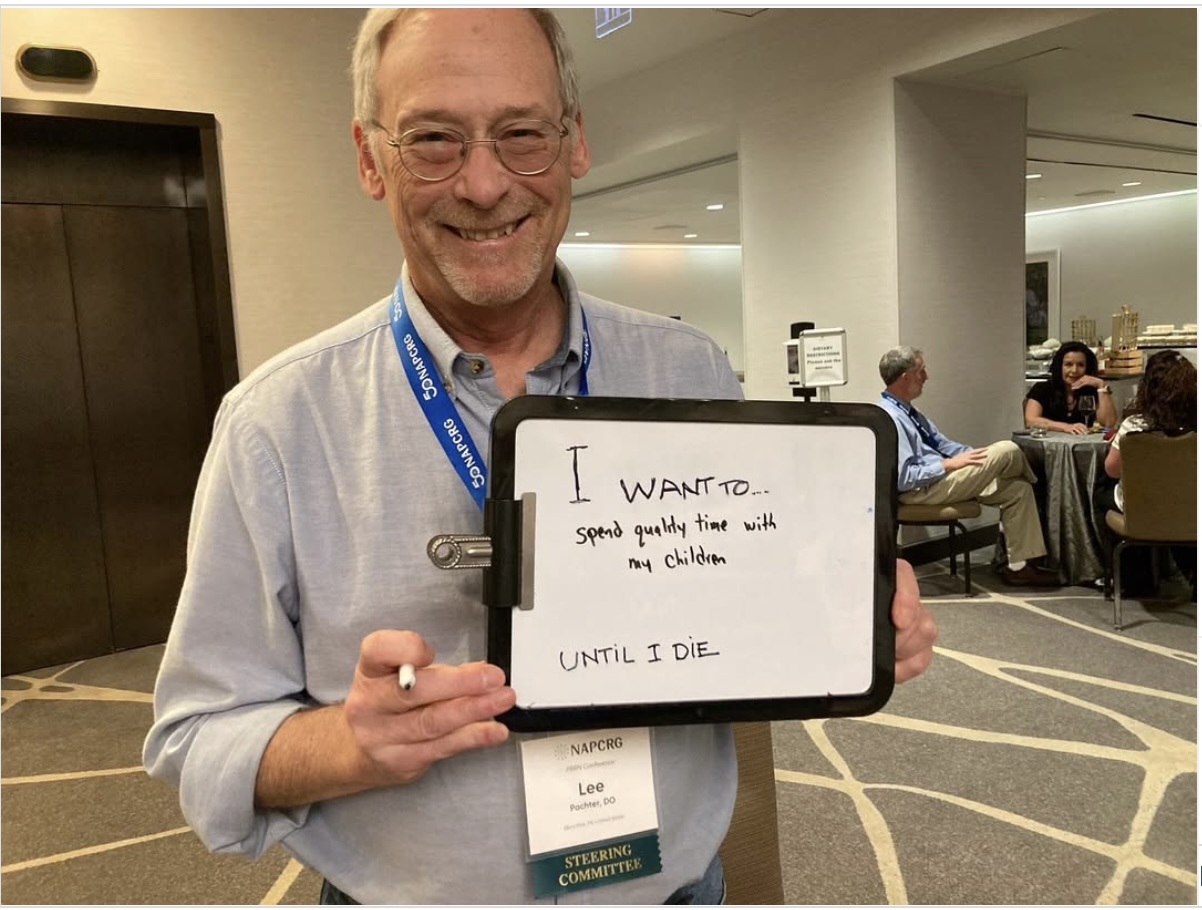

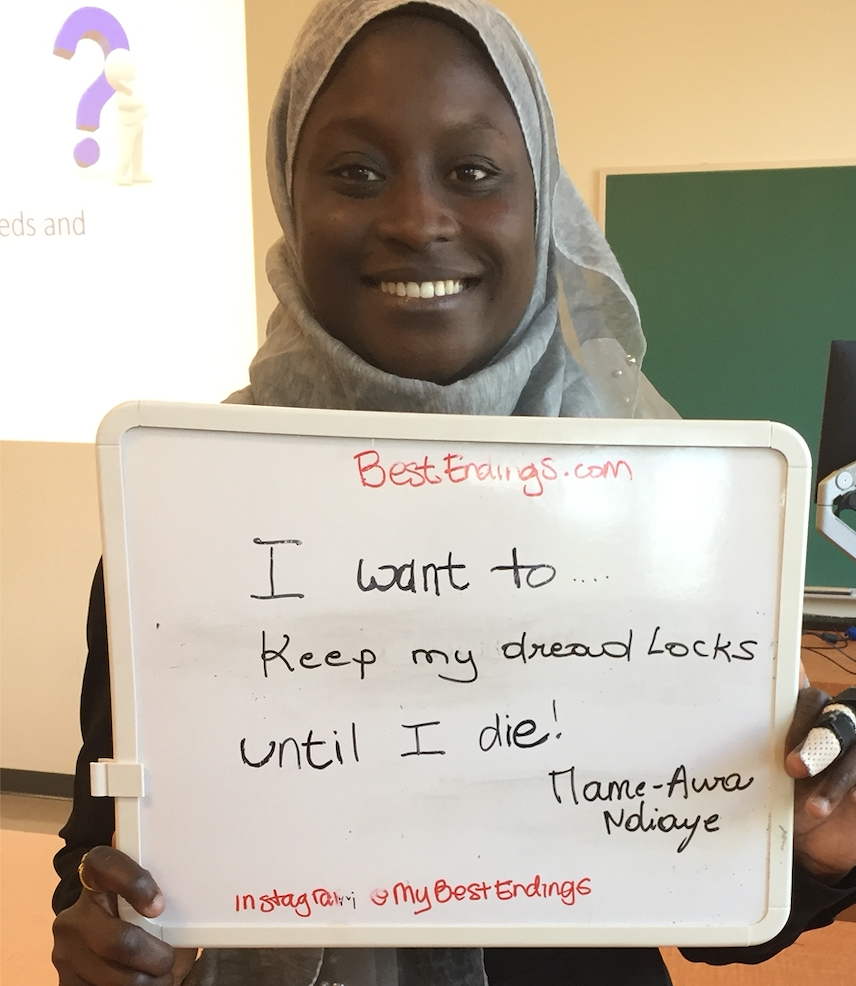

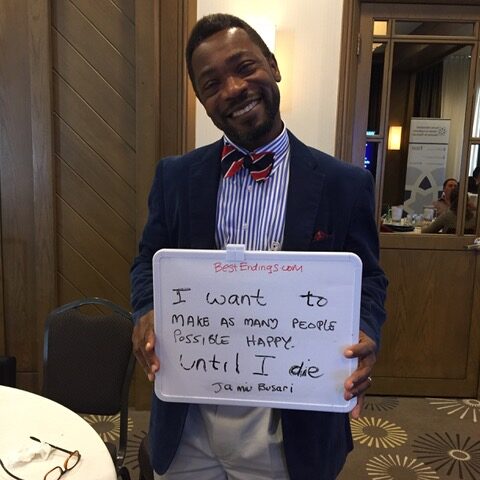

Photos of Danielle Martin, Lee Pachter, Mame Awa Ndiaye, Researcher at Laval University, and Dr. Jamiu Busari, Professor at Massstrict University