As Canadians mental health continues to deteriorate – it is now ranked three times worse than pre-pandemic levels – people are increasingly turning to AI chatbots, like OpenAI’s ChatGPT, for support. An article published in the Harvard Business Review found that in the last year, the top use for Generative AI (GenAI) was as a “therapist or companion.”

But whether chatbots can safely provide the type of care they are so often used for remains unclear. With the rapidly evolving nature of AI technology, much of the research needed to determine the potential harms or benefits of using chatbots as a mental health tool – particularly in the longer term – has yet to be completed.

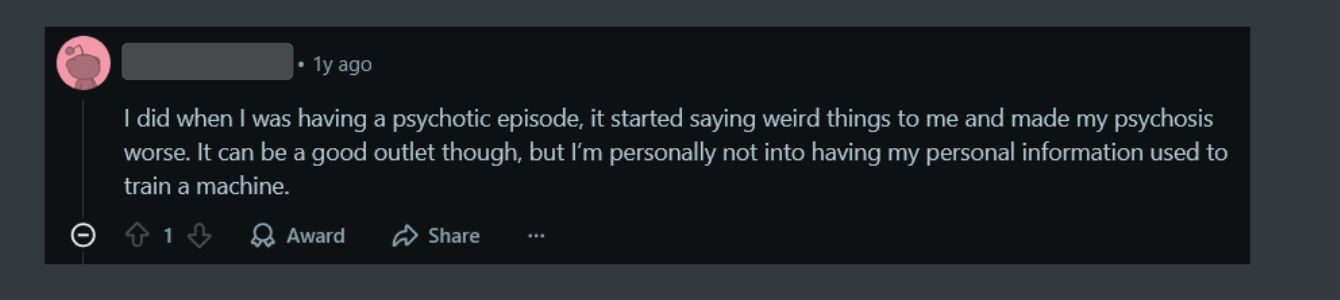

There have been several incidences where AI chatbots have exacerbated and possibly even instigated episodes of psychosis, suggested violent harm towards others and actively encouraged suicidal tendencies.

But with more than 2.5 million Canadians lacking access to the care they need, some have championed AI chat bots as the cornerstone of a new era of more accessible mental health care. Many popular AI-powered CBT (cognitive behavioral therapy) apps like Woebot and Youper have been specifically designed by clinical professionals and advertised expressly as therapeutic tools.

And while ChatGPT was not specifically designed to provide mental health support, that has not hindered its widespread use as exactly that.

“We’re facing a crisis of lack of [mental health] support and resources,” says Amelia Knott, registered psychotherapist and registered Canadian art therapist. “It makes sense that people would turn to something free, instant, and accessible when they’re in moments of confusion or suffering.”

But how do we move forward safely? What possible harms do users need to be aware of? What is needed from a regulatory standpoint? And are we accelerating towards a point where AI could effectively replace traditional human therapy?

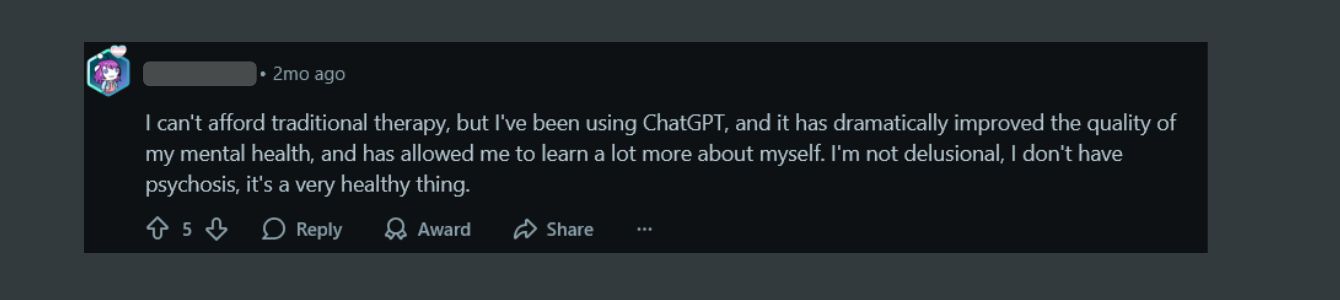

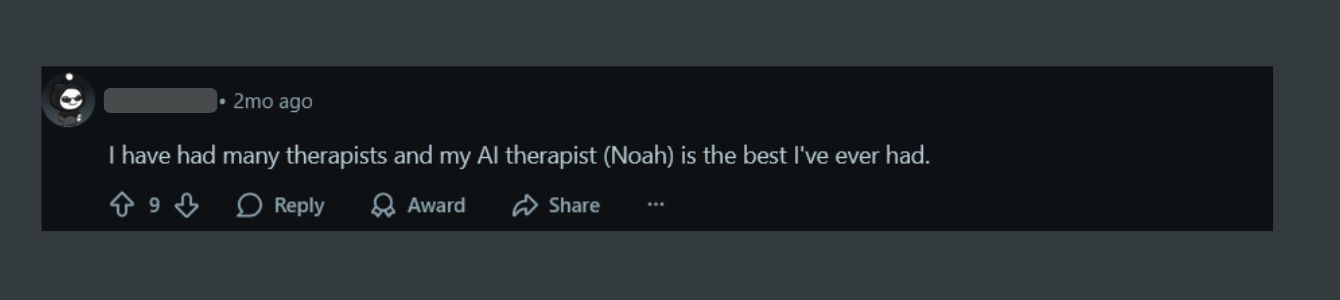

Research assistant Rishika Daswani, along with professor Michael Krausz at the University of British Columbia, recently completed a survey of 300 university students to understand their use of ChatGPT as a mental health tool. “Even just from our initial findings [we’re seeing that] ChatGPT is not necessarily a replacement for traditional therapy, but it is filling some kind of gap for students who may otherwise go unsupported,” Daswani says.

Though the team is still in the early phases of evaluating the responses, Daswani says she was surprised to see that more than half of students rated the ChatGPT support as similar to traditional therapeutic support, with nearly a quarter of respondents ranking it as better.

“It’s not to say that therapists aren’t doing great work, but people may be thinking that because access [to therapy] is so limited … they’re not seeing [therapists] as often as they would like.”

However, Daswani says she is still concerned about its use for more complex conditions, like suicidal ideation, bipolar disorder and schizoaffective disorders.

“AI lacks emotional tone and depth … making it less helpful for complex issues,” Daswani says. “ChatGPT can do really well with things like [offering] grounding techniques for stress and anxiety … But my biggest concern is that I find ChatGPT in particular to be a bit of an echo chamber.”

AI tends to validate what it thinks users want to hear, she says, whereas in a traditional therapist’s office, a professional would challenge some of their clients’ beliefs or encourage them to reflect more critically. She adds that the sycophantic nature of ChatGPT could be contributing to how highly students reviewed the resource.

Many chatbots, specifically ChatGPT, have been rightfully accused of being a bit of a yesman. OpenAI CEO Sam Altman addressed this issue last spring, after pulling a ChatGPT update that had received significant pushback. Users claimed the chatbot was “showering them with praise” regardless of what they said, with Altman himself acknowledging that ChatGPT had become “sycophant-y” and “overly flattering.”

“My biggest concern is that I find ChatGPT in particular to be a bit of an echo chamber.”

This can have a notable impact when used for therapeutic purposes, Knott says. Though chatbot support may feel like a therapeutic relationship, she cautions that the care users receive from AI may not be as helpful as it seems.

“Because the social media landscape is flooded with lots of different products and professionals … with varying degrees of regulation and oversight, it’s hard for the average person to know what support is useful and less useful, especially when you’re logging onto ChatGPT and being met with a validating and reassuring voice,” says Knott.

One review of AI noted the risks of overdependence. “In the context of using AI chatbots to provide therapeutic care, fostering autonomy becomes questionable as the chatbots provide a paradox in which they are available for 24/7 companionship and promise to help improve self-sufficiency in managing one’s own mental health.”

However, there are those who highlight the merits of using AI chatbots as a complimentary therapeutic tool, and several studies also have shown their efficacy when used for specific types of interventions. Experts have pointed to the benefits of using chatbots for general mental health information, to learn about stress management and grounding techniques, and even for mild forms of CBT.

Joseph Jay Williams, professor and director of the Intelligent Adaptive Interventions Lab at the University of Toronto, says his team programmed large language models, or LLMs (the type of technology driving AI chatbots) to enhance therapeutic stories created by human clinicians.

Therapeutic stories are a tool that employs fictional narratives to help individuals cope with emotions and can allow people to draw parallels to their own lives and validate their mental health challenges.

“One thing people found is that even though the story is about someone else, it was more concrete… they found it very relatable…[they] can see [other] people have these struggles and feel connected with it,” says Williams.

While Williams’ team has done a lot of work around wellness and the use of AI technologies, he says he does not believe they should fully replace traditional therapy. He also notes that existing, widely available chatbots like ChatGPT provide little transparency around their programming.

“I think it needs to be clear to people what it is they’ve been provided with and know what is expected,” Williams says. “How do we have custom GPT that comes from reputable sources [where] people can actually see what happens? And how can we have custom evaluators of those GPTs, again, from reputable sources to see what happens. And maybe that’s the place for regulation.”

Regulators, however, have their hands full in the rapidly expanding landscape of apps that functionally provide mental health services, says researcher and associate professor at McGill University Ma’n H. Zawati.

“Seven or eight years ago, there was a ballpark figure of around half a million applications available through major app stores,” he says. “This number is much bigger now and there isn’t a clear system of evaluation and assessment … from a governmental perspective. The ability to actually review [these applications] for the moment is almost unfeasible.”

Much of Zawati’s research focuses on the legal, ethical and policy dimensions of clinical care, specifically data sharing and the use of eHealth apps. He says in Canada, there is currently no regulatory framework specific to AI, though there are health policy regulations set out by provinces. But much of the technology used in clinical settings falls under federal control, via guidelines issued by Health Canada for the development of medical devices.

“We have to keep in mind the issue around the medical advice aspect of a lot of these [apps],” says Zawati. “In the fine print they will tell you that they are not performing a diagnosis … but in reality, that’s what they’re doing … you have to keep in mind that it’s not just how it’s labelled or regulated, it’s how people use it.”

“You have to keep in mind that it’s not just how it’s labelled or regulated, it’s how people use it.”

Even apps designed by clinical professionals, such as Woebot, have gone so far as to explicitly state on their website that they are “not evaluated, cleared or approved by Food and Drug Administration in the U.S.” and that it is “a non-prescription medical device” and “should not replace clinical care.”

Despite Woebot’s warning, one study notes that the website also includes potentially misleading and contradictory statements, such as being able to deliver “individual support through interactive and easy-to-use therapeutic solutions,” highlighting that “traditional mental health care is not always there when it’s needed,” and that “providers need to eliminate waitlists and geographic barriers … the kind of support that Woebot for adults can provide,” alluding to the app having the capabilities to replace traditional therapy.”

In Canada, a national guidance team has been tasked with creating a set of guidelines, tools and resources to help practitioners, organizations and health leaders in “efficiently evaluating and implementing AI-enabled mental health and substance use health-care services and solutions.”

Zawati says that in the existing AI chatbot landscape, he is primarily concerned with privacy. “In the case of mental health, these mental health logs – for example, chat transcripts and sensor data – can be reused to train algorithms. Users usually do not appreciate these downstream uses of the re-identification risk.”

One study notes the need for increased encryption and transparency around the sharing of private health information, flagging that, “as users of a growing number of AI technologies provided by private, for-profit companies, we should be extremely careful about what information we share with such tools.”

“The best way [moving forward],” says Zawati, “is to ensure people have the proper tools to know exactly what to look for when downloading these applications and what to be concerned about. A lot of these applications, their business model is to collect data and … reuse it, sell it or train their algorithms … it’s not necessarily as a service. Once you know that, the expectations become a bit different.”

Although data on ChatGPT is anonymized, risk of re-identification is real, especially when combined with other available data sources. Recently, ChatGPT histories of suspects of crime have even been used in law enforcement efforts.

OpenAI’s Altman said himself during a podcast interview that ChatGPT does not have to abide by the same legal confidentiality agreements that a professional therapist does.

Daswani and others say chatbots may be most useful in replicating some of the basic techniques used in CBT, particularly when using bots specifically designed for these purposes. Knott says for specific clients, chatbots can be used to break down stressful tasks into more manageable pieces.

However, even when chatbots are designed for specific therapeutic purposes, various studies have flagged their limitations, citing a lack of emotional nuance and complexity and struggles that AI has with deeper understanding and empathy, particularly “regarding trauma or severe psychological distress.”

Rachel Katz, a PhD candidate at the University of Toronto whose research centres around the use of AI in mental health, argues that there always will be something inherently valuable in the human connection that we develop with mental health professionals.

“There’s a special kind of relationship that has a set of [unique] characteristics … I don’t actually think that AI tools are capable of filling that role.” For Katz, things like psychological courage, the mutual capacity for vulnerability and interpersonal trust are all core tenants of something called the “therapeutic alliance,” which she argues cannot be replicated by something non-human.

“It’s not that I don’t think that the models are not sophisticated enough yet,” says Katz. “I don’t think that something that is not human is able to enter into that kind of relationship.”

Knott also highlights the importance of this relationship. “Really, what the research shows is that the determiner of success in therapy isn’t necessarily the modality or specific interventions used by the therapist,” Knott says. “The instrument of change in therapy is the relationship between the client and the therapist.”

“We think that [chatbots] are eliminating difficulty and making everybody happier, but I am not sure that’s the case.”

When asked whether a chatbot therapist could be better than nothing at all, Katz raises a further concern. “It’s hard to say,” she says, “My fear is … that if we say that this is good enough for most people, or for people who don’t live in cities, I see that continuing to further marginalize marginalized populations that are already more at risk of experiencing mental health problems and are unable to receive adequate help.”

“I don’t want to see [chatbots] replace the basic therapy benefits in a corporate health insurance plan, or as the primary suggestion for people living in remote communities, for example.”

For Katz and Knott, part of the purpose of therapy is the difficulty baked into the process, and while AI can provide some useful suggestions or breakdown steps to address a problem, it is the inherently human struggle that makes therapy useful.

“AI is built for user satisfaction. It’s not necessarily going to have the kind of human texture, or rupture, repair and deepening like [human] relationships have,” says Knott.

Adds Katz: “I’m curious about how using AI for therapy pushes us towards thinking that we can perfect what therapy is… and what kind of person that leads to the creation of. We think that [chatbots and other similar technologies] are eliminating difficulty and making everybody happier, but I am not sure that’s the case.”

I do think this article is quite well balanced and provides excellent information on this topic for a short piece. It was encouraging to note the author wasn’t promoting trying to have chatbots eliminated from healthcare in some way since that is not going to happen. At any rate, what this article summarizes on the topic more or less aligns with what Perplexity indicates when I asked it the title of this article, result for anyone interested:

https://www.perplexity.ai/search/ai-and-the-mental-health-crisi-zUdweM_TTJ2XfF63RQj5XA

Typical of articles on this site which are largely health care providers promoting their own interests.

1. Canadian mental health is deteriorating because we are constantly bombarded with messages about victimhood not resilience. Therapists have an interest in creating long-term patients, rather than helping patients end therapy. The goal should be “I measure my success by how quickly you no longer need me”.

2. Therapists fear technology because it could put them out of work. This is the same Luddite attitude that radiologists and lab doctors have: technology can replace them and make them unemployed. So they play a rear-guard defence action objecting to technology.

We should embrace AI in the health field. It will reduce costs, improve access and benefit patients. Patients are the focus, not your incomes!