Imagine you and a group of friends have arranged to have dinner together. Your group has just been seated at a nice restaurant, and a neatly dressed waiter promptly delivers a basket of freshly baked bread – warm to the touch, aromatic, irresistible. You can feel the anticipation in the air, as you’re all so, so hungry. Everyone reaches for a piece and starts to dig in …

Except for you. Because to you, that seemingly innocuous and desirable piece of sustenance embodies your personal swallowing nightmare.

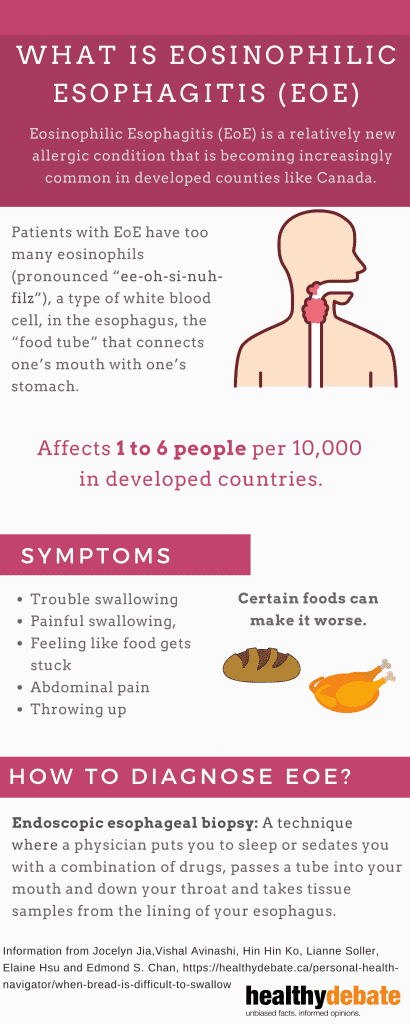

That’s the reality for many patients with Eosinophilic Esophagitis (EoE for short), a relatively new allergic condition that, by some estimates, affects  about 1 to 6 people per 10,000 in developed countries. Although it’s classified as a rare disease, EoE is becoming increasingly common in countries like Canada, in which the proportion of the population affected by allergic diseases – such as food allergy, eczema, and asthma – continues to rise.

about 1 to 6 people per 10,000 in developed countries. Although it’s classified as a rare disease, EoE is becoming increasingly common in countries like Canada, in which the proportion of the population affected by allergic diseases – such as food allergy, eczema, and asthma – continues to rise.

Essentially, patients with EoE have too many eosinophils (pronounced “ee-oh-si-nuh-filz”), a type of white blood cell, in the esophagus, the “food tube” that connects one’s mouth with one’s stomach. Eosinophils are normal participants in our immune system and play important roles in keeping us healthy. However, having too many in the esophagus is abnormal and can be a sign of disease. Furthermore, patients with EoE often have other allergic conditions such as anaphylactic food allergy, asthma, atopic dermatitis, and allergic rhinitis. A patient with atopy – a genetic predisposition favouring the development of allergic conditions – and difficulty swallowing is a suspicious combination.

Patients with EoE can have a number of symptoms such as trouble swallowing, painful swallowing, feeling like food gets stuck, abdominal pain, throwing up and more, all of which have the potential to severely impact patients’ quality of life. Certain foods – bread, or meat for example – can make these symptoms worse. The only tools you have to avoid these “dry’” foods altogether are chew excessively until the food is nearly mush or drink sips of water or other liquids to help the food down as smoothly as possible.

Currently, EoE is diagnosed by a technique fancily termed “endoscopic esophageal biopsy” that means a physician puts you to sleep or sedates you with a combination of drugs, passes a tube into your mouth and down your throat and takes tissue samples from the lining of your esophagus. It’s not exactly a fun way to spend a couple of hours but it’s the only reliable method we have to make the diagnosis.

The invasiveness of this procedure, the fact that the symptomatology of EoE can be variable and nonspecific (meaning the symptoms can apply to other diseases as well), and the reality that EoE is still relatively rare (meaning EoE is probably not the first thing physicians think about when you tell them you’re having trouble swallowing) all combine to produce a significant problem: delayed diagnosis.

The unfortunate reality is that currently, patients with EoE often wait not days or weeks but years before they’re given a diagnosis, meaning they could suffer from seemingly unexplained symptoms for a frustratingly long time before they finally find out what’s going on. This diagnostic delay has been described by researchers and physicians from all over the world. Once diagnosed, there are a number of management options but none are easy and all are riddled with their own pros and cons.

So, how do we move forward?

As well as the factors mentioned above, there are a number of other issues such as resource limitations, cultural preferences and physician education that are important to consider.

Our goal in writing this article is to bring EoE into the spotlight for two main groups of people:

First, medical school students. The reality is that during medical school, there isn’t enough time to learn about every disease with the same depth. Often, less well-known diseases like EoE are sidelined in favour of more common conditions. An orientation toward lifelong learning is already taught in medical schools and that foundation must be built upon. Educating the generation of learners that will go on to make these diagnostic decisions is one way to advocate for patients with EoE and improve their care.

Second, we hope this article is informative for those not involved in the medical field, packaged in a way that’s relatively easy to swallow, so to speak. Less well-known diseases don’t often get much attention in the public sphere either but they are no less important and impactful to the patients and families affected.

*Potential conflicts of interest

Jocelyn Jia, Lianne Soller and Elaine Hsu have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Vishal Avinashi has been an advisory board member at Avir Pharma.

Hin Hin Ko has received funding from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals and Adare Pharmaceuticals.

Edmond S. Chan has received research support from DBV Technologies; has been a member of advisory boards for Pfizer, Pediapharm, Leo Pharma, Kaleo, DBV, AllerGenis; is a member of the healthcare advisory board for Food Allergy Canada; was an expert panel and coordinating committee member of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)-sponsored Guidelines for Peanut Allergy Prevention; was co-lead of the CSACI oral immunotherapy guidelines, and was a member of the committee for the American Gastroenterological Association & AAAAI/ACAAI Joint Task Force guidelines on the management of eosinophilic esophagitis.

The comments section is closed.

I have a choking sensation, like the food is stuck and my throat is constricted, when eating breads, rice or pasta. I used to get terrible heartburn from these same foods, which are not typical heartburn-causing foods, and now it has progressed to this stage. I can usually control it with just drinking water with the food intake and don’t get to a point of bringing up or fully choking, but it is concerning and very uncomfortable. So far, avoidance is the only option I’ve found, would love to find out more about alternate treatments.

I feel like I’m going to asphyxiate and sometimes expel whitish phlegm. Pretty much only at lunch if I eat a sandwich or bread. It’s scary but this article has enlightened me to consider options.

It sounds like my problem – I no longer eat sandwiches as I feel like the food is stuck in my throat & has on a few occasions made me sick. Also I am part of a family who all have allergies,

Hello :)

This reaction appears similar to what I have been experiencing for a number of years, decades even. I have managed through trial and error of foods, but I have had a number of episodes that have caused me to “choke”, usually brought on by bread, cakes, and even rice. Needless to say, I avoid these foods along with eggs and certain types of alcohol (wine, craft beers, etc.) I would be curious to read more information on EoE. If anyone could suggest research that could help me understand why it develops in people, and that could provide me with some ideas on how to manage it more effectively, I would be grateful.

Sincerely,

Dennis Budgell

Finally, now I know…. very scary especially if driving and eating a burger makes me choke and throw up. Dangerous . I no longer eat while driving.

I think I’ve had this scary condition my whole life… very enlightening to read this article. Many thanks

Such a good article!