For years, health care spending in Canada (both public and private) grew much faster than the economy. Until very recently, this trend was expected to continue, casting doubt on the sustainability of Canada’s health care system. However, recent data from the Canadian Institute for Health Information shows that growth in health care spending in 2013 and 2014 has been much lower than expected.

And Canada is not alone: the United States and the European Union have both seen significant slowing in the growth of health care spending over the last few years.

But, while this slowdown in growth is a welcome relief for cash-strapped governments, Canada’s experience in the 1990s suggests it might be just a brief break before spending resumes a sharp upward trend.

Has Canada made a permanent bend in the cost curve, or is this just a temporary reprieve?

Canada’s slowdown

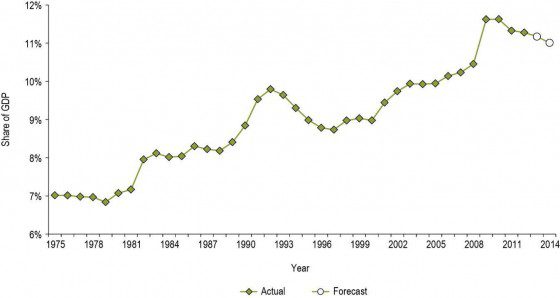

From 2000 to 2010, Canada experienced 7% average annual growth in health spending, which was well ahead of economic growth, which grew by only 2.2% on average over the same period. However, since 2011, the growth in spending started to slow – at 3.3% average annual growth from 2010 to 2012.

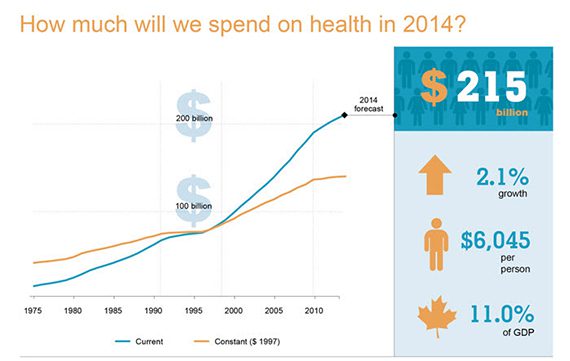

In 2014, growth in total health care spending (public and private together) is projected to drop to only 2.1%, lower than the rate of economic growth.

As a result of this slowdown, the share of Canada’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) spent on health care is set to decrease for the first time in nearly 20 years, from 11.3% in 2012 to 11% in 2014.

From 2000 to 2010, hospitals, drugs and payments to doctors were the major drivers of health care spending. But over the last few years, spending growth in these areas has slowed down.

Drug spending in particular has seen almost no growth over the last four years, thanks to patents expiring on some of the most commonly prescribed drugs, such as Lipitor. At the same time, generic drug prices have also been reduced in several provinces, and prices on both brand name drugs and generics have been further reduced by negotiating through the Pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance. As a result, drug expenditures are expected to increase by only 0.8% in 2014.

But the most dramatic changes in spending have been in capital expenditures, which include the purchase of medical equipment and construction projects. Spending on capital is projected to have decreased by 6.5% in 2013 and another 7.8% in 2014. However, the overall contribution of this decrease is minor, because capital expenditures are a relatively small share of health care spending – only 4% of the total, compared to nearly 16% for prescription drugs.

The US and European experience

Canada is not the only nation experiencing slowed growth in health care spending. This trend has also been seen in Europe and the United States, following the economic crisis of 2008.

In the US, the growth in health care spending between 2009 and 2012 was the slowest seen in 53 years.

Since 2011, the greatest decline in health care spending growth in the US has been in skilled nursing facilities (US term for Long Term Care facilities), retail prescription drugs, retirement communities and Medicare spending. Like Canada, slow growth in drug spending has been driven primarily by expiring patents on blockbuster drugs. Spending on skilled nursing facilities was largely limited by cuts to the rates Medicare pays for some services, and Medicare spending in general has been constrained through provisions in the Affordable Care Act and the Budget Control Act.

Europe too saw significant stagnation and even decline in health care spending after the economic crisis.

According to Chris Kuchiak, Manager of Health Expenditures at CIHI, “many governments [in Europe] found themselves in deficit positions” following the economic crisis. As a direct result, most European governments adopted austerity measures that included constraints on health care spending.

David Morgan, an expert in health expenditures with the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), notes that like Canada, some of the declines in health spending in European countries occurred in the areas of prescription drugs and capital investments. However, some of the European countries hardest hit by the crisis – Greece, Portugal, Spain and Ireland – also saw cuts to health care services, including inpatient and outpatient care.

Now that the worst of the global recession has passed, health care expenditures in Europe are once again on the rise, but the rate of growth is still well below pre-crisis levels, says Morgan.

Canada’s experience in the 1990s

This is not the first time Canada has seen a decline like this. During 1970s and 1980s, health care expenditures averaged 7% of the nation’s GDP, and by 1992, health spending had grown to 9.8%. But beginning in 1993, growth in health care spending began to slow, and the portion of GDP spent on health care dropped back to 8.7% by 1997.

Kuchiak explains the mid-1990s “was [a] period of fiscal restraint where government was focused on balancing budgets.” This restraint included permanent reductions by the federal government to the health transfer payments it made to provinces.

From 1992 to 1997, the greatest slowdowns in growth were in the areas of hospitals, payments to physicians and capital expenditures. Only spending on prescription drugs saw significant growth during this period.

Importantly, from 1992 to 1997 there was virtually no growth in capital spending. However, capital spending then suddenly increased by over 50% in 1999. A similar, though less dramatic, pattern was seen for payments to doctors in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Hospital spending also began to grow sharply in 2000. As a result, health care spending as a portion of GDP was back to 1992-levels by 2003, and continued to grow rapidly for the next ten years.

A number of factors contributed to this rapid growth. Growth in payments to doctors was primarily driven by hikes in the prices paid per service, a rise in the number of doctors graduating from medical school, as well an increase in utilization (the volume of services doctors provided – for example, the volume of hip and knee replacements performed per year more than doubled between 1997 and 2007).

Growth in hospital spending was also driven in large part by increases in the wages of other health care workers (such as nurses) and increases in the number of workers employed by hospitals (a factor tied in large part to the corresponding increase in utilization of doctors’ services). Growth in both the wages and the size of the hospital workforce during this period outpaced growth in the general economy.

The rapid increases in health care spending that occurred after the mid-1990s raises the question of whether history will repeat itself, and therefore whether Canadians should expect health care spending to soon resume its sharp upward climb.

History repeating itself?

Livio Di Matteo, a professor in health economics at Lakehead University, notes that both the current and 1990s slowdowns followed large recessions. However, he observes that in the 1990s, the federal government was experiencing a high debt burden, while interest rates were extremely high. “That alone put a lot of pressure on the government to balance its budget and restore fiscal sustainability. That led to the large [federal] transfer reduction,” he says. Today’s interest rates are much lower than those of the mid-1990s, leaving governments with more flexibility to run deficit budgets.

This is reflected in the approach governments have taken to reducing health spending. Di Matteo notes that the measures taken in the 90s were “very traumatic” and were a “crude blunt set of instruments used to reduce spending and it led to wage loss, compromised access, etc.” In his view, “the current reduction is a gentler one.”

Temporary blip or permanent gain?

Kuchiak believes that at least some of the reductions in spending reflect structural efficiencies that have been introduced, such as pan-Canadian negotiations of prescription drug prices.

He also notes that the reductions in the Federal health transfer scheduled for 2018 may serve to curb growth in spending. “If you have less growth in spending in terms of transfer payments that means provinces and territories will have to either come up with money out their own source revenue, or they will have to rein in spending,” he says.

But some of the recent slowing of health care spending growth may be fleeting.

Di Matteo notes that capital spending is relatively easy for governments to reduce in the short term, by postponing capital projects like new buildings or diagnostic equipment, but that these cannot be postponed forever.

Drug development is also cyclical. While Canada is currently benefiting from many expensive drugs coming off-patent, the next blockbuster drug may be just around the corner, he says.

Kuchiak also believes that the demand on the health care system will only increase as the population ages. Growth in spending due to the aging population is only forecasted to be about 1% per year, but he notes that 1% annual growth will add up over time and could eventually result in substantial increases in health care spending, unless structural changes are made to where and how care is delivered to the elderly.

But the crux of whether – or how dramatically – the recent slowdown reverses will turn on two key factors: the price and volume of health care services.

The price of services is determined in large part by the rates paid to health care workers, and on this front the news may not be good. While Ontario’s government has recently succeeded in constraining payments to physicians through aggressive collective bargaining, history suggests that these gains will be short-lived.

On the volume front, ongoing freezes to base funding for hospitals in Ontario will likely keep utilization from growing in the short term (though these freezes may negatively impact patient care if left in place for too long). Efforts are also underway to reduce unnecessary (and harmful) utilization by improving the appropriateness of care. And these efforts could be reinforced if more doctors are moved off of fee-for-service payment models, which incentivize doctors to provide a high volume of services (though whether alternative payment models ultimately reduce costs is a matter of some debate).

It is impossible to predict with certainty what will happen to health care spending in the next few years. However, while there are important differences between the current slowdown and the 1990s, it seems unlikely that spending growth will remain low without intentional and ongoing action at all levels of the health care system (both public and private) to control both the price and the volume of health care services. Difficult choices may need to be made about which health care services are actually of value to patients, how and where they are delivered, and how much we are willing to pay for them.

The comments section is closed.

There were two really big guys on the camp I was at. They ate a lot everyday and they worked out a lot everyday. Eat 6–8 meals per day and work out for like 5–6 hours or more everyday. If you put that amount of time into anything in life you are going to become good at it really quickly. Or see the results a lot faster than the person that only does it for an hour a day. I dont really know anything about lifting weights https://jbhnews.com/supplements-to-get-ripped-beginners-guide/23676/ , I’ve never been into it. I do however know that all those supplements that get taken with an hour workout is not going to produce better results than working out for 5–6 hours per day and eating the right foods. When in prison and you have 10 hours a day to burn, you have the free time to workout all day. You don’t have to drive across town or go home from work to do it.

One reason to exercise some caution in interpreting the apparent health spending slowdown:

The 2013 and 2014 spending estimates in the most recent NHEX report are forecasts, not actual spending figures. They are derived from provincial governments’ budget projections for planned spending (2012 is the most recent year where actual spending information is available).

The CD Howe Institute recently published a nice summary report on this issue that reveals that actual health spending has outstripped forecasted spending for 12 of the past 14 years, resulting in these forecasted figures being revised upwards in future NHEX reports:

http://www.cdhowe.org/pdf/e-brief_185.pdf

That said, the evidence overwhelmingly suggests that we are indeed seeing a very real reduction in the rate of Canadian health care spending growth; however, we won’t know the true magnitude of this reduction until the actual spending figures become available.

It may reflect a slowdown in health care spending, but it certainly does not tell us whether this increased efficiency is positively correlated with improved patient outcomes and experience. This is where the rubber meets the road.

I think that the slowdown in health care spending is neither temporary nor permanent. It is part of a cyclical phenomenon related to budgets, econromic factors, human nature and other unpredicatble things.

However, i do think the governments, consumers, patients and policy makers have come to terms with the idea that provincial spending on health care or any other item cannot be limitless. And that as our population ages, we will have to make smarter choices about how we spend on chronic disease managment. There seems to be greater emphasis in Medicine today on disease prevention and rehabilitation, rather only on treatment. Disease treatment should be seen as only on part of what we are accountable for as health care consumers and deliverers .

Taxation revenues also seem to be maxed out.

I am hoping that the slope of the line has changed and is much less steep and that we find better ways to prevent, manage, rehabilitate and treat diseases. It seems that we have no choice in the matter.

As a knew jerk reaction would expect to see the numbers go up over time with the aging population growth at no less than 15% now, but fear of losing public health care will demand numerous strategies from government agencies on all levels to address issues. Hopefully a creative solution will resolve. Regardless all we can do is hope for the best

Matthew Mendelsohn and I wrote about this last year in the Toronto Star and HealthyDebate: Doomsday consensus on health care costs proves false

http://www.thestar.com/opinion/commentary/2013/11/06/doomsday_consensus_on_health_care_costs_proves_false.html

Published on Wed Nov 06 2013

Health spending in Canada grew by only 2.6 per cent this year, according to the Canada Institute for Health Information (CIHI). That’s a far cry from the 7 per cent annual spending increases between 2000 and 2010.

This is the fifth straight decline in the growth rate and the third year that per capita health spending has dropped in real terms. As a share of GDP, Canada spends 11.2 per cent today, down from a high of 11.6 per cent three years ago. It’s fair to say that health care spending in Canada has essentially flatlined since the economic downturn of 2008-09.

This all happened despite the almost universal belief among opinion leaders that health spending is out of control and will bankrupt provincial governments. Opinion pages were littered with experts convinced that Canada was doomed to crippling increases in health care spending as the population aged.

Depending on the particular political preference of those making the claims, Canada either had to privatize the system, raise taxes to cover ballooning spending or “have an adult conversation with Canadians about facing reality.” Those of us who suggested that sensible, practical reforms were possible within the current model were dismissed as denying reality.

So, now we know the “doomsday consensus” was wrong. What happened?

Well, looking at the most successful province, Ontario, the numbers are striking. For three years in a row, health care spending has increased by about 2 per cent each year, less than the growth rate of the economy. As a percentage of GDP, Ontario is spending six-tenths of a percentage point less on health care than three years ago.

Quietly and effectively, Ontario policy-makers have tackled each of the major cost areas within the system. For example, spending growth rates for hospitals, physicians and drugs are down dramatically due to structural reforms in the system.

In reality governments were paying more than necessary for health care during much of the past decade and growth was unreasonable. New technology investments produced real improvements in health care, but governments had not recouped the resulting productivity gains. So, while many procedures were now easier and quicker to perform, prices had not come down.

The “true costs” of providing many health care services have been going down for a long time, but only recently did governments apply more disciplined pricing. We’re starting to see spending fall more in line with underlying costs.

Government reforms brought down the cost of generic drugs, the 2012 agreement with the Ontario Medical Association has had a real impact in slowing the growth of physician salaries, and Ontario hospitals have shown real leadership, encouraging the government to invest funds in community care and to introduce pricing reforms..

Most importantly, while spending has come down, Ontario appears to have maintained timely access to care. Surgical wait times declined by about 8 per cent this year and Ontario now has the lowest wait times in the country. CIHI reports that the standardized mortality rate in hospitals has dropped by 11 per cent over the last three reported years in Ontario. There is little evidence that access or quality has suffered over the past four years as we have wrestled real growth in spending close to zero.

But more needs to be done. We need to continue to explore different ways to compensate physicians. We need to continue to move patients more quickly from acute care in hospitals into community care. We need to expand telemedicine and electronic and mobile health technologies. We need to adopt more evidence-based practices known to improve patient outcomes. We need to continue to revisit difficult questions about end of life care. We can do all of this.

The reforms of the past few years are not complete. They are a work in progress. If we continue to drive health care reforms across the system, we’ll realize more savings. We can expect several more years of low or no growth in health care spending which will allow fiscal room for other investments

We were told we’d go broke as spending rose 6-7 per cent every year and baby boomers gobbled up services. Well, data released last week suggest the doomsday consensus was wrong. Let’s give credit to the reformers who have been making progress to improve our system — and continue to support their efforts.

Matthew Mendelsohn is Director of the Mowat Centre at the University of Toronto. Will Falk is an Executive Fellow at the Mowat Centre and an Adjunct Professor at Rotman School of Management. They co-authored the 2011 report: Fiscal Sustainability and the Transformation of Canada’s Healthcare System, available at http://www.mowatcentre.ca .

Will I like your hopeful commentary. Spending growth is down across the OECD countries following the big fiscal pressure caused by the global economic collapse. Spending rates in the mid-90s when the feds pulled back dramatically were depressed for several years – and then roared back. As you note, reform of physician payment is not where it needs to be, which is focused on value and sharing risk on performance and quality (not volume) with the places where physicians work. Likewise for prospective payment for acute care and home care tied to reducing cost growth while enhancing value. Hats off to any of the reformers who can get us there.

Terry Sullivan