In the waiting room at the breast imaging centre, there is a sea of women in blue gowns. Some are seated. Some are standing, leaned against the wall, looking at their phones or just looking around. They are young and they are old. Tall, short, fat and thin – with hair and without. On this day there are no men, but I’ve seen them here because men get breast cancer, too. I close my eyes and my sisters in blue fade like waves on a horizon. I focus on the metallic chatter from the TV and the clamoring ring of a phone no one has answered. I want to hear music; I want to hear the street sounds. I don’t want to be here. None of us do. Yet all our hope lies here, in the waiting room.

One of the cruel aspects of this disease is that it hits us in such an intimate part of our bodies. Practically speaking, the breast is more expendable than some other parts of us. We can remove a breast and go on living. But they’re also an inextricable part of who we are. They’re a site of pleasure. They also feed our babies. They represent, in many ways, the cycle of life.

So, when someone takes a waterproof pen and draws a map across them or leads us into a dark biopsy room to remove a part of them, a part of us can go missing, too. When a patient is told she can potentially save her life by having a breast removed, it raises a complex array of feelings. Breasts, while not necessary for our lives, are far from vestigial. And it can be very painful when we have to say goodbye – in part or in full – to them.

Maybe that’s why in the past 50 years there’s been such an emphasis on reconstructive surgery to rebuild (or build anew) the breast that’s taken. It’s common wisdom among many that a woman will want to reconstruct her breast to feel more like her old self. The right to breast reconstruction has long been understood as an issue of freedom, bodily autonomy and choice. In Canada, breast reconstruction is funded as a part of our national health system because although it’s an aesthetic procedure, it has a positive impact on some patients’ mental health. When U.S. insurers denied claims for reconstructive surgery, women’s health advocates went to court; in 1998, Congress passed the Women’s Health and Cancer Rights Act requiring health insurers who cover breast cancer treatments to also cover the costs of breast reconstruction.

So, what are the choices?

Among breast cancer patients in Ontario in 2018–19, 3,860 had mastectomies (removal of one or both breasts); 12,102 had breast-conserving surgeries (removing the tumour and some additional tissue, also called lumpectomy); 4,090 had breast-reconstruction surgeries. Three of the most popular reconstruction surgeries in Canada are the latissimus dorsi flap (that transplants tissue from a back muscle to the breast), the DIEP flap (that moves tissue from the belly) and saline breast implants. Tissue can also be rearranged in the same or opposite breast, a procedure offered to some women who have breast-conserving surgery.

About 60 per cent of women having breast cancer surgery in Ontario in 2018–19 did not have additional surgery on their breast other than tumour removal or mastectomy. This includes those with lumpectomy procedures who may decline or are not candidates for reconstruction.

Saying no to reconstruction stratifies partly by age, with older women less likely than younger women to have reconstructions or other interventions. In the U.S. today, 50 per cent of single-mastectomy patients opt out of reconstruction and 25 per cent of double-mastectomy patients opt out, according to a study published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

For women who decline reconstruction, there is no added surgery or recovery time. With reconstruction, each surgery has its own protocols. According to the University Health Network, the average latissimus dorsi flap with expander surgery protocols takes two surgeries and six weeks’ recovery time. The process for saline implants commonly involves two, two-hour surgeries; DIEP flap surgery takes 6-10 hours with a four-day hospital stay and an 8-12 week recovery period. With some of the reconstructive procedures, a spacer is placed to stretch existing breast tissue between surgeries.

There is another option – aesthetic flat closure (going flat). It typically adds about two hours to tumour removal surgery and has an average two-week recovery period, with longer surgery and recovery if it is done separately after tumour surgery. Of these, 2,134 are performed each year in Ontario. About one out of seven women in the province having breast-conserving surgery or mastectomy gets a flat closure.

Google “going flat” and you’ll find Instagram selfies of lush, tattooed flat closures and coverage of fashion shows featuring women who chose to go flat, with an emphasis on body positivity. Through “Flat and Fabulous” blogs and social media groups, women share photos of the beautiful, flat-style dresses they’ve found for their weddings – and of date nights, smiling with their partners, no prostheses required. Judging from the community that’s been growing over time, going flat has been a positive choice for many women.

But most Canadian health-care websites make only passing mention of the choice to get a flat closure – or no mention at all.

I’ve been wondering why.

Tattoo by Amy Black. Photo courtesy of Not Putting on a Shirt. Source of original image: https://notputtingonashirt.org/2020/08/30/mastectomy-tattoos-with-artist-amy-black/

When Abigail Bakan, a political science professor at the University of Toronto, had a bilateral mastectomy in 2016, she decided from the start she didn’t want reconstruction. “I said no. And they had it on my record,” she told me. But members of her cancer care team asked her, repeatedly, if she was sure. “That’s when I started thinking, ‘Why are they are continually asking the question and there’s only one right answer?’ The ‘right’ answer is you’re supposed to say yes.”

A social worker on Bakan’s cancer team recommended that she attend the Breast Reconstruction Awareness Day event in Toronto, known as BRA Day. BRA Days are held at various venues across North America, including community centres, convention centres and hospitals. “BRA Day brings together women currently facing breast cancer with leading breast reconstruction surgeons,” reads the press release from Toronto’s event. It features seminars for patients about different reconstruction techniques as well as a Show and Tell Lounge where breast-reconstruction patients tell their stories (and show results) to women who’ve been referred to the event by their physicians.

The logo for BRA Day features a pink cancer ribbon with a symmetrical pair of loops resembling breasts and the tagline “Closing the loop on breast cancer.” The logo reflects the idea that constructing a new breast can be a liberating alternative to wearing a prosthesis or facing potential social stigma around appearing without a prosthesis.

This seems to be the spirit behind plastic surgeon and Canadian BRA Day co-founder Mitchell Brown’s comment in 2017 that “if a woman has had to have one breast removed, there is awkwardness and difficulty in trying to create balance when they get dressed every day.”

As Toni Zhong, a Toronto-based plastic surgeon and conference organizer, put it: “We now know that you don’t have to live with a mastectomy defect for the rest of your life and there are options available that can restore your breast to make you feel and look good or certainly better.”

But what if a patient doesn’t see her mastectomy or lumpectomy as “awkward” or a “defect?”

The women in the Flat and Fabulous movement are pushing back against the idea that they’re not whole without their breasts, blending online organizing around breast cancer care with image galleries that bring greater visibility to women who have chosen flat closure. One organization, Not Putting on a Shirt, uses social media to provide vetted information on topics such as body image, communicating with providers, emotional health and local community supports.

In this sense, the Flat and Fabulous movement has done more than introduce a new aesthetic option. It’s pushed for better shared decision-making and choice (two concepts that are key in the reproductive rights movement) in breast cancer care.

This shift is needed. Across Flat and Fabulous platforms, women are telling their stories of recovery from botched surgeries or of “explanting” implants for various reasons, including serious health issues.

Yet many say that they were not made aware of risks, statements that are borne out in research. A cross-sectional survey in the U.S. in 2017 found that just 43.3 per cent of breast cancer patients had made a “high-quality decision (about reconstruction), defined as having knowledge of at least half of the important facts and undergoing treatment concordant with one’s personal preferences.” Many hospital websites and most of the major American clinical breast-reconstruction decision aids do not include the option of flat closure (a notable exception being the Breast Advocate app, developed by plastic surgeon Minas Chrysopoulo).

This kind of information gap can have a negative effect on women’s quality of life. A 2017 study confirmed earlier research that patients are more likely to express decision regret when they have not been engaged in shared decision-making around post-mastectomy decisions, with this being true both for women who wanted reconstruction and those who wanted a flat closure. “Patients often felt pressure from their clinicians to choose one option or another,” according to the study, with some feeling that bias was at play and others feeling rushed to decide on the spot.

It may seem odd that some women must press their surgeons to get a flat closure, but it happens. A study of 931 women in 2021 by UCLA’s Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center found that 18 per cent of recent mastectomy patients had been told there were no options for them to choose to go flat. In five per cent of cases, women were given surgical results that they didn’t ask for, with the surgeons leaving additional tissue instead of a flat closure; what the researchers called “intentional flat denial.”

According to Deanna Attai, a California-based breast surgeon who co-authored the study: “Some patients were told that excess skin was intentionally left – despite a preoperative agreement to perform a flat chest wall closure – for use in future reconstruction, in case the patient changed her mind.” Attai notes, “We were surprised that some women had to struggle to receive the procedure that they desired.”

Why would a surgeon disbelieve a woman who wanted a flat closure instead of a reconstructed breast?

I asked Kimberly Bowles, the founder of Not Putting on a Shirt, about her own experience. Bowles says she had communicated to her surgeon that she wanted a flat result: “I wanted to be ‘one and done,’” she says. “All I wanted was to get back to my normal life caring for my children, ages three and one at the time.”

But as she was going into surgery, she was told by the surgeon that he would be leaving excess skin in case she changed her mind later. In the months following surgery, Bowles was devastated. Seeking later to revise the surgery to a flat closure, she had a difficult surgery following her radiation, with infections that landed her in hospital for a week. After confronting the hospital and dealing with the aftermath of the experience, Bowles connected with other women who’d had similar experiences and became a leader in the Flat and Fabulous movement.

Bowles acknowledges that experiences like hers represent a minority and that denying women the option of a flat closure “is often not malicious.” Sometimes the lack of choice represents gaps in training, education and standards of care. Even when women have a surgeon who will do the procedure, those in the U.S. often must deal with denials by insurance companies that have not caught up with the practice and have no reimbursement codes for it.

Getting more surgeons to present flat closure as an option requires more than training or insurance changes, however. It also requires a paradigm shift away from the idea that a woman must have breasts to feel like a real woman.

To date, much of the surgical training has been focused on restoration of what’s been lost, notes Bowles. So, when some surgeons are told by patients not to reconstruct a breast, they may hesitate. “It’s hard for some to accept,” she told me. “It feels wrong.”

But what if a patient doesn’t see her mastectomy or lumpectomy as “awkward” or a “defect?”

Echoing this sentiment, Susan Love, author of a best-selling book about breast health, told the New York Times this year, “Surgeons became so proud of what we were able to do that we may have forgotten that not everybody may want it.”

There is also the problem of a data gap, with little information collected on how satisfied women are when they choose to go flat. Recent data is interesting, however. A 2019 systematic review of 28 studies found that women who went without reconstruction fared no worse and sometimes better than those with reconstructed breasts, with no notable differences in terms of “quality of life, body image and sexuality.” Some of this was confirmed by results of the 2021 UCLA study that Attai co-authored, which showed that 75 to 90 per cent of women who underwent mastectomy without reconstruction were satisfied.

But in a data-driven field, there needs to be more research to form a better understanding about navigating the decision-making process.

The history of breast cancer surgery is a grim chronicle of trial, error and slow progress. Lumpectomies have been performed since at least the 14th century. Rudimentary mastectomies are documented in the 19th century, including the mastectomy of Abigail “Nabby” Adams, the daughter of U.S. President John Adams, who underwent an early mastectomy while tied to a chair in her parents’ home with no anaesthetic or antiseptic.

In the late 19th century, American surgeon William Halsted developed the radical mastectomy, removing the whole tumour in one piece along with the pectoral muscles, lymphatic vessels and axillary lymph nodes. While the procedure saved lives, it also led to pain and disability.

In the early 1930s, the modified radical mastectomy was developed, sparing some women pain by retaining muscle in the chest. Then, with advances in radiation and chemotherapy, research showed that some classes of patients who were treated with a lumpectomy (removal of tumour with an extra margin of tissue) and radiation had similar survival rates to women treated with only a mastectomy. As a result, in the late 1980s, the concept of breast-conserving surgery became more popular.

Before reconstruction became commonplace, women who had mastectomies were typically offered a range of prostheses – balls of cotton fabric and wool placed in the bra or bras with built in shelves and prosthesis.

Although surgeons in the first half of the 20th century experimented with reconstructions that used the woman’s own tissue (autologous reconstructions), it wasn’t until 1963 with the development of silicone breast implants that reconstruction surged in popularity. But these implants also created health risks and led to numerous recalls, explants and class action lawsuits.

They still carry risks and complications. Most recently, textured breast implants, which were used in thousands of procedures, were pulled off the market by Health Canada in 2019 because of a rare risk of lymphoma. Amazingly, some women have struggled to get provincial health coverage to have them removed. Women in the U.S. are similarly battling with insurers for coverage to have various types of breast implants removed.

In 1979, the first modern autologous breast reconstruction was performed, opening a door to alternatives for women choosing reconstruction. These procedures continue to carry risks, however, including limited mobility in sport as well as mastectomy skin flap necrosis (tissue death) that can cause scarring, deformity and lead to more interventions. A 2018 study of 2,300 Canadian and American women who had breast reconstruction between 2012 and 2015 found that women with autologous reconstruction experienced higher rates of complications than women with implants.

In her book The Cancer Journals, Black feminist writer Audre Lorde fought for body acceptance after her breast cancer surgery in the late 1970s, rejecting the admonishment of her surgeon’s office to wear a prosthesis. “There is nothing wrong with the use of prosthesis if they can be chosen freely,” she wrote, but “after surgery I did not feel better with a lambswool puff stuck in the front of my bra. The real truth is that certain other people feel better with that lump stuck in my bra.”

Lorde, who would face health battles for the next 14 years before succumbing to metastatic breast cancer in 1992, wrote powerfully about the contrast between her own concerns and those of the representative of the American Cancer Society’s Reach for Recovery Program who visited her following surgery to talk about how prosthesis could help her overcome “embarrassment.” Lorde noted that the biggest changes she faced were not aesthetic, but rather existential: “My concerns were about my chances for survival, the effects of a possibly shortened life upon my work and my priorities,” she wrote.

Lorde was frustrated that some others seemed unable to move the conversation beyond the breast to approach the larger transformation in the arc of her life, as a person living with cancer. For Lorde, going without a prosthesis was a way to bring the authenticity of the cancer experience into the public view, challenging taboos not only around gender, but also around illness.

It seems amazing that more than 30 years later, we are dealing with some of the same tensions. When comedian Tig Notaro, who went flat after a double mastectomy, ripped off her shirt in the middle of 2012 stand-up shows in New York and L.A., she shocked the audience. She also fostered a sense of hope and solidarity among breast cancer patients. Notaro exposed the realities of living with breast cancer while also making it clear that the shape of our chests doesn’t – and shouldn’t – define us. “She showed the audience her scars and then, through the force of her showmanship, made you forget that they were there,” critic Jason Zinoman wrote in The New York Times.

The choice to go flat has just recently begun to be normalized within the mainstream of cancer care. The term “aesthetic flat closure” was only adopted by the National Cancer Institute (U.S.) in 2020.

Some of the loudest voices for a new approach have come from women who experienced flat denial. In Quebec, Marie-Claude Belzile wrote in 2017 that her experience inspired her to make change to health care in her community: “I had to fight with my breast surgeon to be flat. Even after I told him multiple times I wanted to go flat, he wrote on my surgery form ‘reconstruction, expanders.’ He finally respected my choice and did a good job, but the fight I had to go through should have never happened.” Belzile, who passed away in 2020 from metastatic disease, started a Facebook page called Tout aussi femme after being diagnosed with stage IV breast cancer. She also founded a French-speaking flat support group called Les Platines.

More women now are opting out of reconstruction.

“Many women (opt out) for comfort, others are athletes and many women … want it to stay simple. Reconstruction is not a simple process,” says Attai, adding that in the past few years more of her patients, especially those with smaller breasts, are opting out of reconstruction.

Women who use their back muscles for work or athletics may be wary of latissimus dorsi flap surgery (which I was offered) because there is a risk it can compromise shoulder function. This and other procedures carry risks including infection and necrosis. Complications may lead to further interventions. In the U.S., one in three women develop a postoperative complication from breast-reconstruction surgery within two years and one in five require additional surgery. In 5 per cent of cases, reconstruction fails.

According to the Journal of the American Medical Association, a study of 2,343 patients found that 32.9 per cent experienced postoperative infections or other complications from reconstructive surgery. A 2017 study of 1,632 women who’d had reconstructive surgeries outlined musculoskeletal and nerve issues in patients at the one-year mark.

The study’s authors wrote: “A concerning finding was that physical well-being at one year did not return to baseline levels for women. This study reveals an important unmet need in reconstructive breast surgery. Specifically, although current techniques may restore how a woman looks, they do little to address how she feels physically.”

While a patient can give informed consent when knowing the risks, too often breast cancer patients have not been made aware of those risks. The UCLA study found that just 14 per cent of patients were aware of potential complications of reconstruction – but 57 per cent reported that they had been informed of the potential benefits to reconstruction procedures. The team concluded that: “Implementation of uniform surgical management and improved respect for patient consent in this population would result in significantly improved patient experiences.”

Illustration by Sindu Sivayogam.

I was interested to see the word consent in the UCLA paper. While breasts are a part of gender, sexuality and reproduction, terms like choice, consent, shared decision-making and autonomy – common in the lexicon of gynecology – seem less common in breast cancer care.

I had a look at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Ethics, which shows a thoughtful perspective toward the concept of shared decision-making: “A signed consent document does not guarantee that the patient’s values and priorities have been taken into consideration in a meaningful way and that the ethical requirements of informed consent have been met. Meeting the ethical obligations of informed consent requires that an obstetrician-gynecologist gives the patient adequate, accurate and understandable information and requires that the patient has the ability to understand and reason through this information and is free to ask questions and to make an intentional and voluntary choice, which may include refusal of care or treatment.”

More women now opt out of reconstruction.

I asked Todd Tuttle, a professor of surgery at the University of Minnesota, whether professional organizations in the field of breast cancer would be following this lead, with more guidance on fostering informed decision-making. “They’re going to have to,” he said, pointing out, “we’ve moved from paternalism, where the treatment plan was basically dictated by the surgeon often to the woman’s husband,” toward an atmosphere of greater choice and autonomy for patients.

Tuttle notes that whether patients decide to have reconstruction or go flat, one key quality of life indicator is whether they felt they were able to have a real choice in the decision.

“If you give them enough time and enough information, they’re more likely to be happy five years afterward and they’ll feel like they made the right decision. Those people who are not satisfied often felt rushed or pushed,” he says. “I think time is probably one of the most important aspects of shared decision-making for breast cancer.”

In Canada, our underfunded systems lead to a different kind of rush. In seeking to care for everyone but with limited resources, our clinics lack capacity. Time often seems like a luxury – but with reconstructive surgery, waiting can actually help mitigate risk. A 2018 study found that patients who delayed reconstruction were significantly less likely to develop complications than those who chose to do their reconstruction immediately.

As it turns out, everybody in cancer care needs more time. A 2020 assessment of burnout among Ontario oncologists noted several factors, including “poor/marginal control over workload, working atmosphere that feels hectic/chaotic and insufficient time for documentation requirements.”

As policymakers and administrators look back on health care during the pandemic, they have an opportunity to make the lasting changes that will protect health care in the next crisis while improving patient care and provider quality of work life.

“I think we don’t talk as much with patients as we used to,” says Tuttle. “There’s all this documentation on electronic medical records and doctors are trying to get all that done instead of just talking to patients. The only way you can have those (important) conversations is by taking your time and listening.”

As we spoke, I thought back to the day of my diagnosis. I had brought a list of questions to the appointment (which I attended alone, due to COVID restrictions). My doctor pulled out a pen and wrote a series of quick notes about the specifics of my diagnosis … on the room’s examining table paper. After he rushed off to see other patients and I was alone in the room, I carefully tore the examining table paper, folded it and put it in my purse to read later with my husband. When I got home, it was inscrutable – an experience we would have again when results were posted in the online Patient Portal.

It was all information, to be sure. But it didn’t replace a conversation.

I switched to a different hospital, with a doctor who scheduled an in-depth introductory Zoom meeting about my care and choices. I remember being grateful that she took the time. I also recall that this conversation took place at 8:30 p.m. My new provider was making time for her patients by working after hours. Most likely, it was the only way she could.

“The problem with breast cancer is you have to make these irreversible life decisions in a really short time,” says Tuttle, “and you’re making the decisions at probably the most stressful point in your life.”

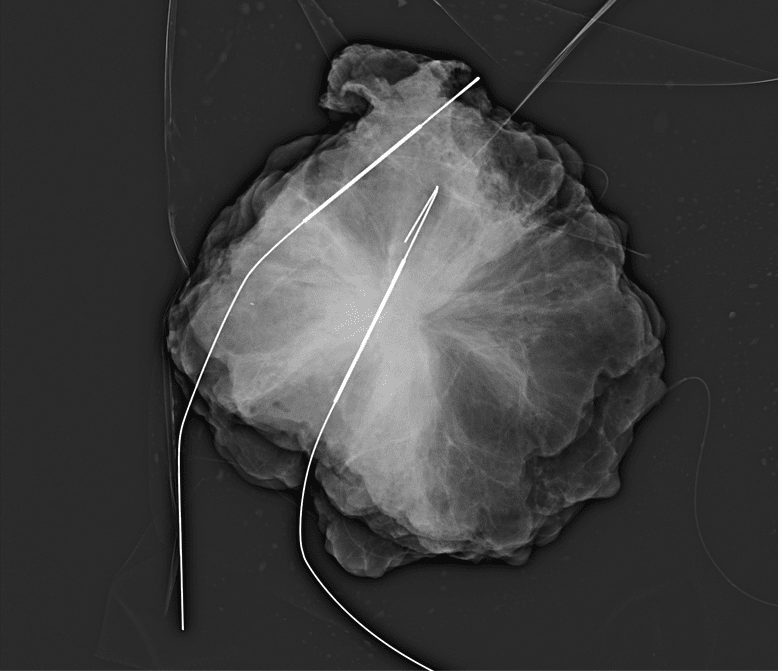

A photograph of Anne Borden King's tumour prior to its surgical removal; the white lines are pieces of thread-like medical equipment inserted into the tumour to help surgeons quickly locate it. King recalls: "I opened the images late one night and was struck by their appearance, like variegated blossoms in white and black." (Photo courtesy of Anne Borden King).

Throughout breast cancer treatments, our relationship with our bodies changes. During chemo our hair falls out, our weight fluctuates, bizarre things happen to our fingernails and skin. We get sick and sometimes can’t stay awake. The radiation burns us; those put into chemical menopause are doused in hot flashes. Pain and discomfort are part of the whole deal. And while there are some small decisions we have control over during treatment, most of us simply take the treatment plan handed to us if we want the best chance to get well. The choice of whether to reconstruct or go flat is different. This decision isn’t about fighting cancer; it’s about healing from the fight.

After my lumpectomies for synchronous bilateral cancer, I was offered a reconstruction. Because they removed more tissue from the right than the left, the plastic surgeon’s plan was to recreate a symmetry between my right and left breasts. But this choice would have involved a lot more than ticking off a box and signing a consent form (which I was offered in a flurry of papers before even seeing the consulting plastic surgeon) – and after months of cancer interventions that had too often kept me away from family and work, the thought of more surgeries exhausted me. I was ready to start reconnecting with my body, which already had become a site of multiple, difficult interventions. For me, rebuilding my relationship with my body didn’t involve rebuilding my breasts.

I was also not convinced by BRA Day’s claim that I could “close the loop on breast cancer” with plastic surgery. As I write this, I have a 20-year prescription for preventative meds in the hopes of staving off metastasis. Breast cancer is a part of my life now. What if, instead of “closure” through a facsimile of my pre-cancer body, I strive to accept the myriad ways that fighting cancer has changed me? Could accepting my post-treatment body help make the reality of survivorship easier, too?

Some of my concerns were like those of Isabelle (who chose not to use her last name), an Ottawa patient whose choice to go flat was supported by her health team. “I made the choice to have prophylactic mastectomies because I have a high risk of developing breast cancer, and I watched my mother die from it,” she told me. “That part of the choice was easy. What I had not really considered was the reconstruction.” In debating a post-mastectomy plan, she said, “I didn’t want to do anything that would require a long recovery, multiple surgeries, time away from the sports and activities I love … Going flat meant that I would not take any additional risks with my health.”

Isabelle echoed a common theme among women who go flat: a sense of wanting to move on with life. “I don’t feel like I am losing my femininity, that I will look like less of a woman,” she said. “My breasts fed my two babies … Now I want to be around for those babies for as long as I can.”

As the going flat movement gains strength from new media portrayals (what Bowles calls “the visibility piece”), will plastic surgeons also give more visibility to the flat option?

Bowles thinks so, noting the Oncoplastic Breast Consortium’s recent amendment to include optimal flat closure in its mission statement. The Canadian Cancer Society also now lists “Choosing to Stay Flat” on its website. Bowles cites practitioner education initiatives as well as a growing discussion in the U.S. insurance industry. As she points out, plastic surgery is a competitive environment, too. Not Putting on A Shirt now has more than 200 surgeons globally listed on its Flat Friendly Surgeon Directory (three are Canadian).

Flat fashion is also getting a toehold in the marketplace. Lingerie companies La Vie en Rose and Victoria’s Secret have launched modular mastectomy bras (the latter designed by Stella McCartney). AnaOno is a line of bras specifically for flat enclosures. Its website reads: “Surgery, no surgery, asymmetry, scarring or discomfort, we support you with comfortable and beautiful options.”

This decision isn’t about fighting cancer; it’s about healing from the fight.

With all the aspects of cancer we don’t have control over, the aesthetic decisions carry an extra weight; they’re personal, yet they also have cultural meaning. As Belzile wrote: “My vision is that the more we speak out about our realities and our fights, the more it’ll change the culture and society … I see a way for getting visible to each other and to others and get validated for who we are. I see a future where women are respected and taken as the only person competent on what’s best for her.”

Back in the waiting room, my mind travels to my visit a year ago, waiting to go down the hall for surgery. X-rays of my tumours would be taken in surgery that day and sent to me later via a secure hospital server. I opened the images late one night and was struck by their appearance, like variegated blossoms in white and black – excised and sampled for cells to see if they got it all. They tried to get it all. We tried, all summer, fall and winter. Did we? I wonder: Did we get it all?

I open my eyes and look around the room. Every face tells a story and everyone here is waiting for some kind of news. Here, our breasts are imaged, mapped and ultrasounded, pressed in the mammogram machine, deconstructed in biopsy. We sit patiently, hold our breath; we bleed, blink back tears. Then at the end of the appointment, we take the elevator down and step back into everyone else’s world to find our way. To reconstruct, resurrect or rediscover who we are.

The comments section is closed.

I got breast cancer in my 30s, double mastectomy, no reconstruction. I am not “happy” because I didn’t choose cancer and my life feels ruined, while my peers are having the best decade of their lives. My prime is clearly over. Breast cancer is basically getting to choose between Terrible Choice A or Terrible Choice B. The idea of putting fake blobs under my skin to mimic breasts or ruin another part of my body to make mounds repulses me. My mother has reconstructed breasts and I don’t even like hugging her anymore, it is like a wall of two rocks between us now. People who do not have a close family member who has been through this have absolutely no concept of what breast cancer/surgery actually involves. My own sister is even still pretty ignorant about it.

Regardless, this has been much harder than anticipated. I did not realize how small minded the world is – particularly other women, and ESPECIALLY female doctors. At a recent check up I did complain about some tissue that was left behind (I am on medicaid and go to a terrible educational hospital) and the doctor wrote in the report that I said my “scars are unsightly” – I NEVER SAID THAT! I only addressed discomfort from a row of tissue/fat the inexperienced breast fellow left behind below my scar. Women often project their own feelings about their body, self-image, breasts, onto ME and I am SICK OF HEARING IT. I have endured enough. Please keep your mouths shut. At my yearly ultrasound screening when the tech calls the doctor to make sure they have all the images they need – I hear the doctor on the speaker phone “when was her last mammogram? She didn’t get reconstruction?!?!?” in a surprised, disapproving tone. The clinic also seems confused when I call to make an appointment, women’s imaging – you mean mammogram? as if ALL women still have breasts to be mammogramed. You’d think out of all places in the world I could be “safe” and understood at the breast clinic/women’s radiology department, BUT NO.

I do not regret my decision to not have reconstruction but I hate being in the world, and kind of hate my life. Breast cancer has robbed me of so much while adding insult to injury in countless ways, socially.

I didn’t ask for any of this. Breast cancer “awareness” doesn’t do a goddamn thing, and nobody has ANY regards for what women go through with these surgeries. Probably because women tend to “grin and bear it.” I don’t. I’m bitter and will continue to complain. This was a very eye opening experience about how ignorant people (in my case, Americans) are. And much of this is rooted in misogyny. You’d think my own mother would be someone I could talk to – but no. I can tell she thinks less of me since my surgery, and it’s depressing. Initially she told me I was asinine for not wanting reconstruction. A few years after my surgery she told me she hopes people won’t think I’m trans because I didn’t get reconstruction. I don’t look non-binary at all. Today she told me “it’s what’s on the inside that counts” as if I’m chopped liver because I’m approaching 40 and breastless. I’d still rather be me, and have no problem attracting men. It’s mainly other women making this so hard for me. This has all been way more alienating and depressing than I ever could have anticipated.

Excellent article. Thank you for highlighting the importance of considering all aspects of quality of life that makes us choose to be flat. It is not right to put anyone in the position of suffering for years to get flat chest because in the mind of the medical team , there is not need to remove healthy tissues/organs.

This article is missing another option: autologous fat grafting. Women can donate fat from their own body, which is then purified and use that to fill the breast. Roughly 70% of fat graft volume survives. I personally would not want to get breast implants, due the risk of them triggering autoimmune disease. Other concerns include risk of encapsulation, capsular contracture, and implant replacement requirements every x years (more surgeries), etc.

Excellent article. I chose flat 5 weeks ago with a double mastectomy. Thankfully, my breast specialist/surgeon supported the decision I made. My husband is incredibly supportive, as well. The breast we prophylactically removed had a very small invasive tumor that wasn’t picked up in MRI or mammogram. After many years of implants, replacements, implant removal, biopsies, etc, I am done with breast surgeries!

The flat option allows a person to heal more quickly and get on with their life. I have no regrets, whatsoever.