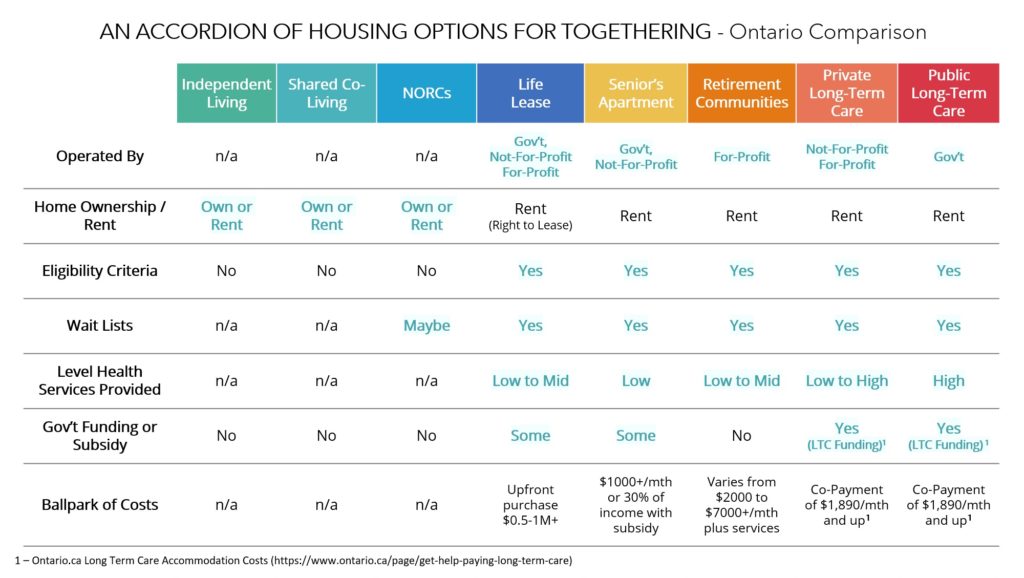

This series has shared a handful of family stories to illustrate the realities and nuanced considerations of Togethering – how we care for each other intergenerationally. Now we examine the most common housing options available to seniors. By no means is this an exhaustive list, and for some, financial reality may place some of these options beyond reach. Rather, consider this a roadmap for exploratory conversations with the elders in your life.

An accordion of housing options

During our interviews with families at various stages of Togethering, we found that many will gravitate toward two polar ends of housing choices –independent living or a nursing home. With more probing, we learned that many of the in-between options, such as seniors’ apartments or life leases, did not come to mind for most individuals, and often were not explored without proactive suggestion. Moreover, the mainstream use of the term “nursing homes” can refer to many types of institutional care, including retirement communities and government-funded long-term care facilities – which offer different and distinct experiences. All of this inspired us to “pull open” an accordion of housing options to evoke greater clarity and prompt creative exploration.

Independent living

On the far left of the “accordion” is Independent Living. For many, this represents the start of your Togethering journey when your elderly relative(s) maintain an independent lifestyle, living in their own home. Your loved one(s) may have minimal needs and can generally manage their day-to-day and home maintenance activities.

The type of housing (i.e., a standalone house, townhouse, etc.) may also play a role in how long an individual can continue to live independently. For instance, a house typically requires more maintenance than a townhouse or multi-story condo/apartment with shared amenities. Stairs are often the earliest barrier for individuals with mobility needs. Financial means can also influence such choices as your family may consider monthly cash flow requirements, large capital outlays (i.e., for major home upgrades such as roofing, plumbing or other structural needs), as well as future appreciation of your real estate assets.

Beyond the practical, there are also many socio-emotional considerations. Remaining in one’s familiar neighbourhood with established friendships and routines can be an important contributor to well-being. Some individuals are reluctant to move out of a home that holds treasured memories, and/or may find downsizing an overwhelming effort. These are all considerations to delicately probe so that everyone feels heard and accommodated. We learned from many families that individuals’ perspectives and needs often differ, even between spouses.

Earlier in our series, we shared Stella’s story, in which she and her husband moved to a home on an adjacent street from her aging parents. This is a great hybrid example – living close to care for one another while maintaining independence and privacy. For other families, hybrid independent living may simply entail living in two condo units or townhomes within the same complex.

With every housing choice across the accordion, adaptations such as outsourcing home maintenance and in-home health services are available. Depending on your senior’s condition and eligibility, some of this may be government funded. For instance, the city of Markham offers snow-shoveling services upon request for qualified residents over 60 or living with a disability. Be proactive to research and explore these options with your LHIN (Local Health Integrated Network) Home and Community Care team, and/or municipality. Ultimately, with these choices, we can extend the time your aging relative can remain home.

Shared co-living

Although the most traditional co-living situation is simply sharing the same house with your elder, this is the most complex as it comes with a host of considerations such as lifestyle compatibility, potential for family conflict and financial considerations. As one interviewee astutely shared with us: “Someone (either me or my spouse) is bound to be an in-law” so co-living families have to delicately balance power dynamics as well as cultivate a shared sense of belonging.

In our profile of Andrea, she shared that her home-buying criteria was specifically oriented toward co-living in light of her dad’s Parkinson’s diagnosis.

Research on best practices for co-living show that single-floor living, independent spaces (i.e., separate kitchens and entrances), and a community-oriented neighbourhood are all top of mind for buyers who are in search of co-living homes. This trend makes sense with our aging population, and with property prices at peak levels where an average GTA home can cost upwards of $1.2M.

Says Alcina Sung, an interior designer who has worked with families to adapt their homes for elder care: “Often I advise my clients to pay attention to key spaces such as bathrooms and kitchens. These are high investment areas and finding homes that are large enough to adapt for barrier-free living can spare a lot of headaches down the road, even if you may not immediately require such upgrades today. You want to have the potential to adapt as cost-effectively as possible.”

Other emerging options include self-contained apartments or laneway houses on the same lot. In some cases, an arrangement might start with the young adults of the family moving into such spaces, and over time, as the family expands with children, the young family may swap homes with the senior(s).

Naturally Occurring Retirement Communities

Naturally Occurring Retirement Communities (NORCs) are private residential communities in which a large portion of residents are over the age of 60. These communities, typically rentals, condos or cooperative buildings, were not originally designed for elders but have evolved based on the demographic of its residents.

NORCs came into the forefront of urban planners and health-care leaders during the pandemic, when hospitals started innovative programs to deliver essentials and vaccines to these neighbourhoods. Building upon that success, the University Health Network (UHN) now has a division focused on fostering community activism and targeted services for NORCs (http://uhnopenlab.ca/work/labs/norc-lab/). You can find a list of NORCs in Toronto as defined by the UHN team here.

Seniors living in NORCs benefit from having greater access to diverse service providers, including health-care services, transportation, meal delivery, etc. At the same time, elders enjoy living in community with other elders, while having their own private residence.

Life Leases

Life Lease communities are also growing in prevalence with private, not-for-profit and municipal options. Life Leases are a category of housing in which owners have a “right to lease” a unit “for life,” but do not hold ownership over the land or building. Instead, an organization that is typically set up as a not-for-profit owns and operates the building and charges a monthly maintenance fee to all residents.

Owners hold a “right to lease” as a transferable asset and when buying/selling, adhere to defined processes as outlined by the Life Lease organization. For example, the organization may use an appraiser to determine the price and charge a flat or percentage-based fee on sale. Also, there may be eligibility criteria for residents– such as an individual must be over 60 to live in the building. The guidelines are intended to create a defined sense of community for residents. Lastly, because there is no ownership of land or building, owners must find their own financing arrangement, typically outside of a traditional mortgage.

Similar to NORCs, Life Lease residents benefit from localized and targeted services, and can live in community with other elders while enjoying the privacy of their own residence.

There are many varieties of long-term care homes – some are run by the government, others are operated by not-for-profit organizations as well as for-profit companies.

There are many varieties of long-term care homes – some are run by the government, others are operated by not-for-profit organizations as well as for-profit companies.

Seniors’ apartments and retirement communities

Unlike Life Leases or NORCs, these units are on a rental basis only with some eligibility criteria and/or subsidy options available. They may be operated by Toronto Community Housing or other agencies such as Baycrest or Yee Hong Centre that aim to serve different populations of seniors. Select senior’s apartments may also offer seniors-oriented services such as emergency call bells, on-staff attendants and other health/home maintenance services.

As a senior’s needs grow to a point where it is undesirable to live on his/her own, retirement communities such as assisted living and retirement homes come into the picture. The distinction between senior’s apartments and retirement communities is in the breadth of services offered.

For example, Baycrest and Yee Hong have independent living seniors apartments as well as designated floors of assisted-living units with more intensive wrap-around care and communal services such as centralized meals and activities. There may be nurses and health-care workers on staff and a defined list of health and personal care services offered with its own price list. These communities can be operated by private agencies or by not-for-profits.

One of the greatest benefits of living in a retirement community is that residents can comfortably transition in the same familiar surroundings as needs grow. This is especially helpful if one spouse’s health condition requires more intensive care before the other. Many of these communities allow spouses to continue living together, or at least within the same complex.

However, finances are a significant consideration as monthly costs for rent and additional services can be more than $3000+ per month, depending on what services are selected and whether subsidies are available.

Long-term care

Finally, there are long-term care housing options that come in two flavours – government-run or privately operated, with funding for care directly provided via the Long-Term Care Act of Ontario. These are typically reserved for individuals who require more than three hours of daily nursing care and are unable to attend to their own daily health and personal needs. By design, these institutions cater to seniors who have more complex needs, which may include conditions such as dementia.

Families interested in long-term care facilities can connect with their LHIN (Local Health Integrated Network) Home and Community Care team for an eligibility assessment, where they will evaluate your elder’s needs and circumstances. They will determine your eligibility for home care (e.g., such as health-care personnel sent to your home for select activities such as toileting, bathing and other essentials) or whether your loved one should be assigned to a long-term care facility.

Once eligibility is confirmed, families can submit a shortlist of homes, which helps the system better match bed vacancies to individual choices. It’s helpful to research in advance which homes you want to choose for your elder relative. Among your considerations, you may weigh factors such as proximity to family, unique care needs, specific language or ethnic offerings and evaluation reports about the home. Depending on the urgency of your situation, it’s important also to consider the length of the waitlist; some extend beyond one year or even 10 for some high-demand facilities. Lastly, it is highly recommended to pay the facilities an in-person visit. This will give you a much greater perspective on fit, accommodations and the workplace culture.

Those are the options. But how do we approach this topic with the senior(s) in our life?

When

According to All in the Family: A Practical Guide to Successful Multigenerational Living, the best time to start these discussions is when your elderly loved one turns 70, barring any earlier onset of needs. This gives everyone time to research, decide and comfortably adapt to a new housing situation before s/he turns 75, when the average senior starts to require more support.

How

Broaching the subject of housing options with an elder often requires advanced preparation and tact. Look for opportunities to introduce the discussion by pointing out experiences of others in your social or family circle and asking for your elders’ opinion on their situation. This may give you a hint of their underlying considerations, hopes and fears for the future.

Approaches to these discussions are as diverse as the families themselves. For some, the conversations have been simple and pragmatic, and especially so if the elder initiates the process and has a clear point of view. Other families draw strength from techniques such as solution-based questions, conscious listening and compassionate conversations to create a trusting environment for exploration and inclusive decision-making.

It’s useful to involve anyone who may be affected by your family’s Togethering choices – this includes siblings (even if they live out of town), children, spouses and extended family, if appropriate. Drawing your “circle of care partners” more broadly will set the stage for greater collaboration down the road and give everyone a chance to offer their perspective and affirm their values.

If there is a history of differences or potential for contention, you may want to proactively invite a facilitator or mediator to the discussion to help create space for open and progressive dialogue. Often tensions can arise if there are different viewpoints on who ultimately is the decision-maker and how a family builds consensus.

By no means is this a straightforward or easy process. In fact, decisions can evolve with lived experience, changing health conditions and life circumstances. Being open, adaptive and informed allows space for everyone to consider the possibilities and to ponder the many and varied what/if/then scenarios that may ultimately allow everyone to achieve a shared vision.

Artwork by Winsome Adelia Tse

Illustration: Shared co-living arrangements where multi-generations of a family live together under one roof are becoming increasingly popular

The comments section is closed.

I’m a customer of residential moving companies. The anticipated cost of a mover is mostly determined by the weight of your possessions and the distance it will travel, whether you are relocating locally (where the cost is based on time) or long distance (where the cost is based on weight) local movers calgary . Make sure you comprehend this estimate of inventory and that it is as complete and accurate as feasible.