This story is part of a series exploring the results of the OurCare survey.

Virtual care is here to stay.

Done right, it has the potential to improve access, equity and patient-centredness. But there are risks – to patient safety, adherence to care guidelines and to health-system costs. Virtual care has also accelerated a stampede of corporations into primary care, the implications of which are not clearly in the public eye.

How should virtual care be integrated into our system? The answer should be informed by patients and the public.

Results from the OurCare national research survey help us understand how people have been using virtual care and their values and priorities for shaping the system. The survey heard from more than 9,000 people across Canada between September and October 2022 and is the first phase of a national initiative to engage the public in the future of primary care.

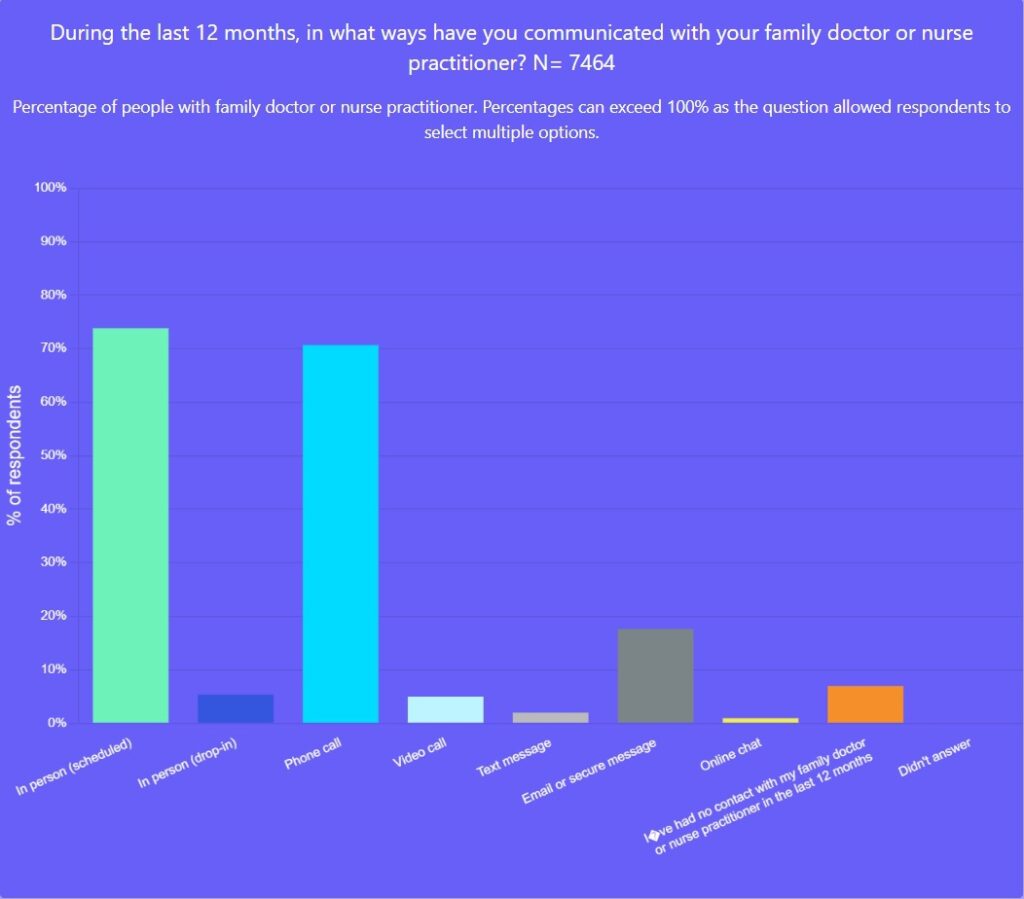

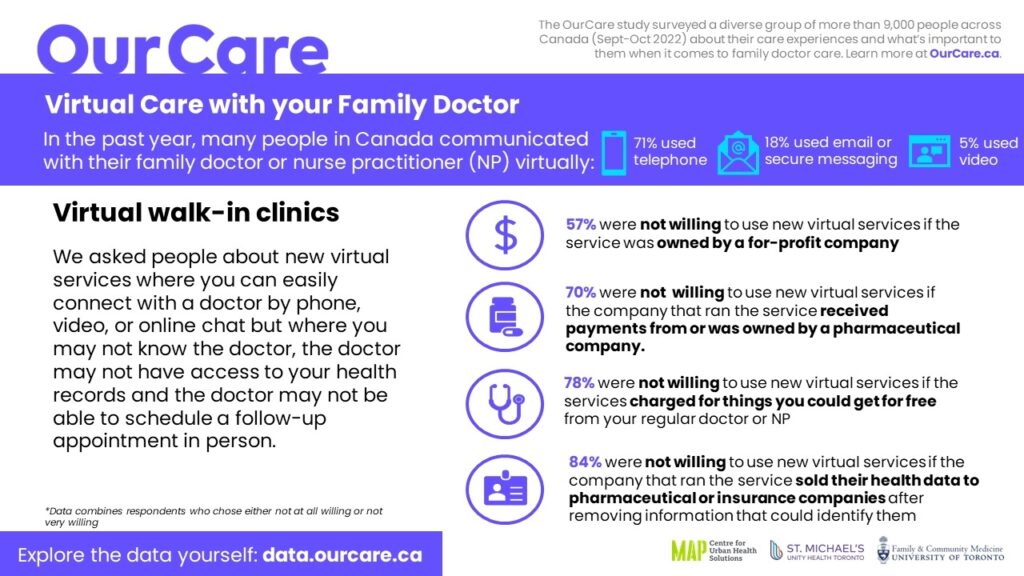

The term “virtual care” has come to mean any means of connecting with your care team other than in person. The OurCare survey results confirm that the majority of virtual care in Canada is delivered by phone – 71 per cent of survey respondents said that over the past year, they had communicated with their family doctor or nurse practitioner by phone, 18 per cent by email or secure messaging and 5 per cent by video.

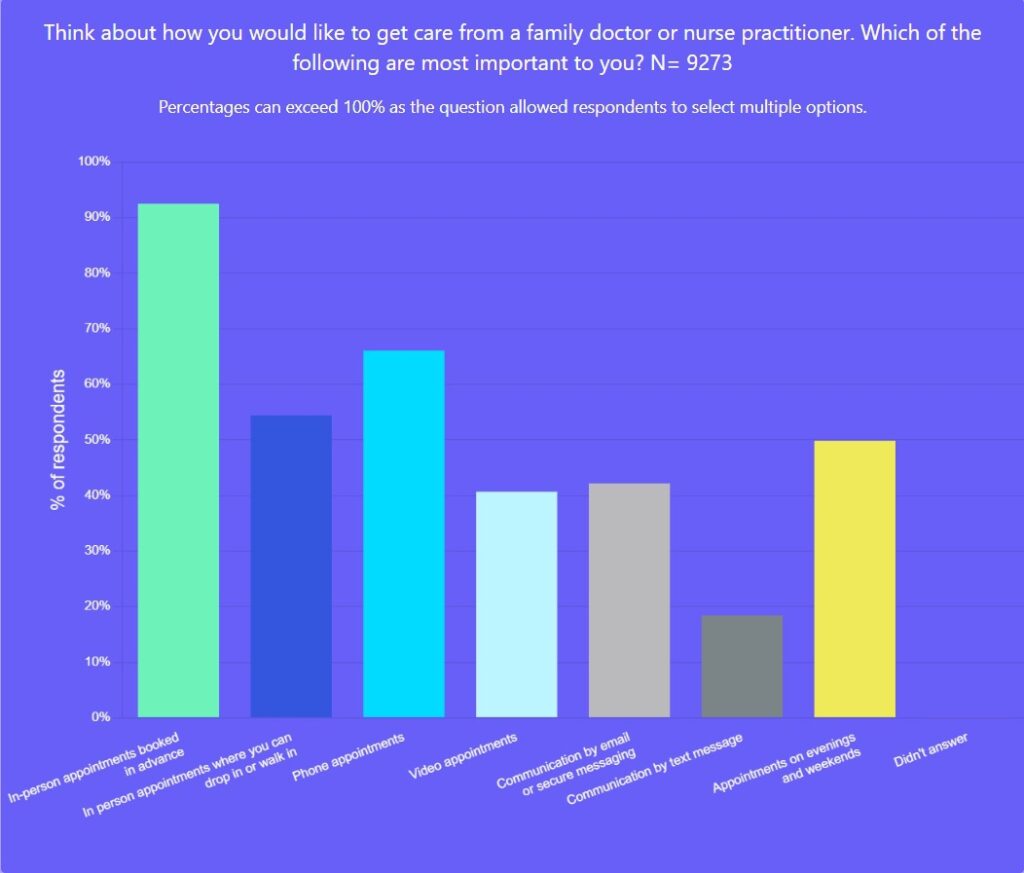

When asked to think about how they would like to get care from their family doctor or nurse practitioner and what was most important, in-person care rose to the top (respondents could choose more than one response): 92 per cent selected scheduled in-person care, 66 per cent phone calls, 54 per cent drop-in in-person care, 42 per cent email or secure messaging and 41 per cent video.

In short, the vast majority of people prioritized being able to see their family doctor or nurse practitioner in person; most also wanted to be able to connect with them by phone. The most common reason people rejected phone calls was because they liked seeing their health provider in person and did not feel connected to their health-care provider over the phone.

Video and email or secure messaging were important to many as well. However, far more people selected video or email as important than reported using it with their health-care provider in the past year.

The survey also shined a light on how people have been using virtual care outside of an ongoing relationship with their health-care providers. Almost half of the survey respondents used a walk-in clinic in the past year, with about a third of those saying that one of the walk-in encounters was via phone and 12 per cent saying it was by video. Virtual walk-in clinics were the second most common setting for people who did not have a family doctor or nurse practitioner to access care for non-urgent health problems.

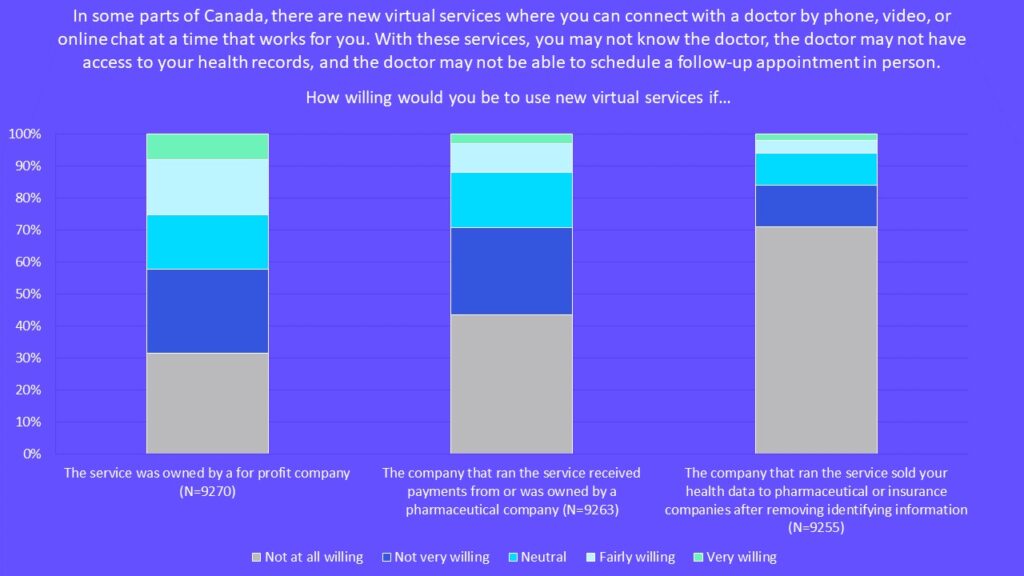

However, despite the high use of virtual walk-in services, survey respondents strongly opposed the involvement of for-profit and pharmaceutical companies.

We asked a series of questions about how willing people were to use virtual walk-in services. We described these as new virtual services where you can quickly and easily connect with a doctor by phone, video or online chat but where you may not know the doctor, the doctor may not have access to your health records and the doctor may not be able to schedule a follow-up appointment in person.

The findings were striking:

- 57 per cent were not at all or not very willing to use new virtual services if the service was owned by a for-profit company.

- 70 per cent were not at all or not very willing to use new virtual services if the company that ran the service received payments from or was owned by a pharmaceutical company.

- 84 per cent were not at all or not very willing to use new virtual services if the company that ran the service sold their health data to pharmaceutical or insurance companies after removing information that could identify them.

Yet, people reported using these services. Why?

Many who don’t have a family doctor don’t have anywhere else to turn. Even those with a family doctor can struggle to get care in a timely way. Only 54 per cent of our survey respondents reported being able to see their family doctor or nurse practitioner within three days of trying to book an appointment urgently. And only half of respondents said they could always or usually get care from another clinician from the same practice when their family doctor or nurse practitioner was away.

As well, many may not be aware of how virtual walk-in services operate – for example, that the services may be investor-owned and shareholder driven, how patients’ health data is used or how the for-profit motive can influence prescribing or other recommendations. After all, how many of us have glossed over wordy consents and clicked “I agree,” not really knowing what we were agreeing to.

We also found that 78 per cent of survey respondents were not at all or not very willing to use virtual services if the service charged them for things they could get for free if seen by their regular doctor or NP. But when people can’t access the care they need in the public system, they may feel they have no choice but to pay privately.

It’s welcome news that the federal government has signaled it will be cracking down on platforms charging for services that ostensibly should be covered under the Canada Health Act – including companies charging for virtual visits for a family physician. But that move will only help patients if there are options for people without a family doctor or NP to access care within the public system.

Many appreciate the convenience of virtual care. But research has shown though that virtual walk-in clinics may be adding more churn to the system, potentially driving more not fewer emergency department visits. These services are also potentially diverting scarce human resources from the type of ongoing, relationship-based primary care that people want and has been shown to improve outcomes. In a time of significant shortages of family doctors, think of the difference that the family doctors or nurse practitioners working for these services could make if they were able to take on patients for ongoing care instead.

We need to design a system around people’s values and priorities. The OurCare survey findings support virtual care services being publicly owned and, whenever possible, integrated into an existing relationship within a family doctor, nurse practitioner or team.

Explore the data yourself at data.ourcare.ca. For more information about OurCare, visit OurCare.ca.

The comments section is closed.

I would like virtual care strongly rooted in public healthcare because technology should never go in front of solid quality Healthcare. It is the study of anatomy, the study of medicine, the study of illnesses, and the study of healing that is important for a healthy and strong population.

A healthcare that looks after and cares for its patients does not come from boosting its technology.

I had never considered that a virtual care provider would be indebted to or owned by a pharmaceutical company. Does that happen now? Is that probable in the future? Some insurers have invested in virtual care companies, but even if they own it outright, insurers already manage sensitive personal information to meet or exceed federal and provincial privacy standards, so that seems like a relatively small concern. The keys to this are legislative and regulatory, and include disclosure and transparency about data destinations and use.

The bottom line remains that governments don’t innovate, companies do. We can’t assume governments have the skillset, tools or even the inclination to make all the improvements we need to health services. (If that were true, we would have a high-performing health system.) There is a government role in innovation, but it is in facilitation, good regulation and oversight, and for selective, targeted investments and incentives.

To your closing sentence, innovation in virtual care or anything else cannot be limited to or require public ownership. Absolutely, it should be integrated into public services, but to date it is much more likely to be seen in private health insurance plans. Perhaps both sides can learn from the other?