The health-care community is actively involved in advocacy in a number of areas, including physical activity, climate change and equity. However, it is strangely silent when it comes to transportation and urban planning (walking, micromobility, public transit and driving), with the conversation turning to individual behaviours – wearing a bike helmet, slowing down when driving – rather than the systemic safety measures that are the bread and butter of public health approaches.

Health-care teams’ communication and campaigns around transportation and traffic safety should focus on a more comprehensive approach: human-centric urban planning. Cycling is a great campaign target because it encompasses areas recognized as important to public health:

– Health (physical activity and climate change): Better bike infrastructure would increase physical activity levels; reduce carbon, air and noise pollution; and support Vision Zero initiatives that aim to prevent all serious injuries and road deaths, a top 10 cause of global mortality.

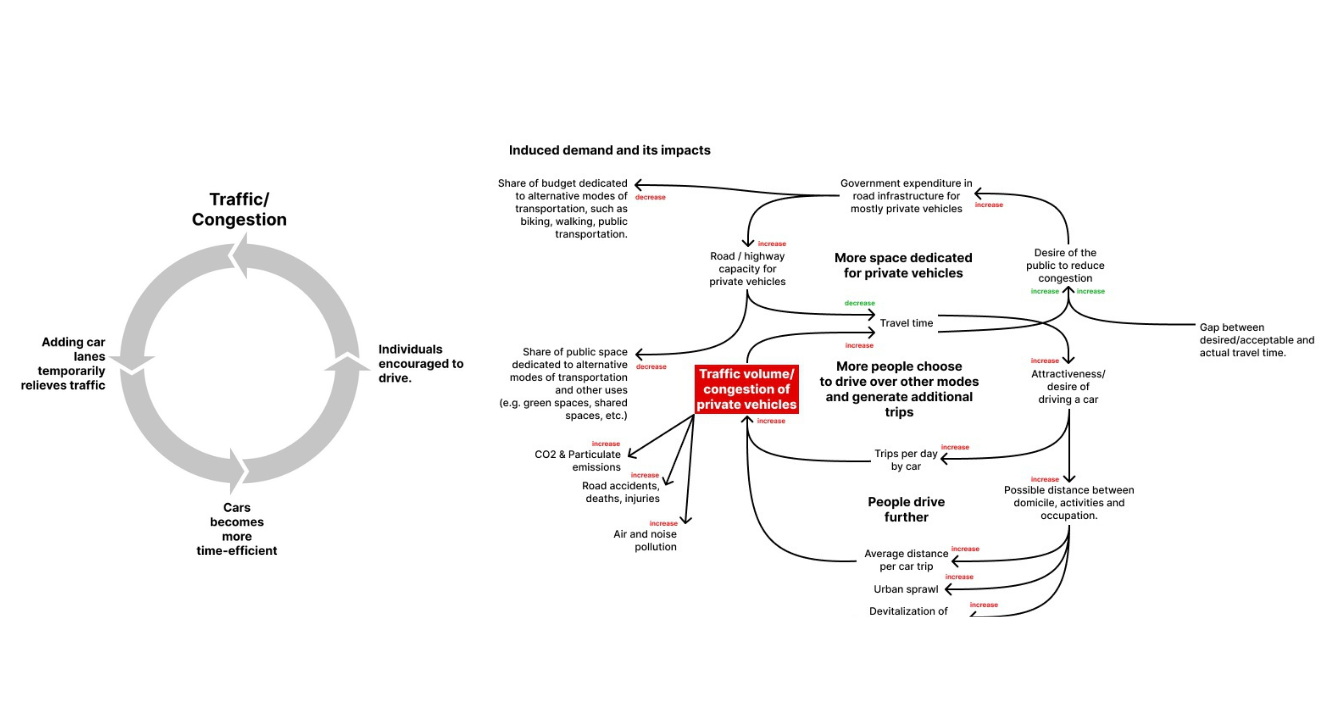

– Equity: City layouts often make biking unsafe and impractical; laws governing vulnerable road users (such as pedestrians and cyclists) are prone to unequal and discriminatory enforcement. As such, individuals are forced to drive and are exposed to higher financial costs. This poses many opportunity costs both individually and at a society level, as car-centricity is expensive and engages in positive feedback loops (Fig. 3) that require additional vehicles and further subsidization/allocation of limited funds.

Health-care teams are well-positioned to educate the public about the positive externalities of cycling and can help dispel many of the misconceptions, based on societal norms and anecdotal lived experience, that discriminate against vulnerable road users, such as:

- Cyclists must wear a helmet.

- Cyclists put themselves and others in danger.

- Most people would never cycle regularly, especially in the winter.

Misconception #1: Cyclists must wear a helmet

Humans are notoriously bad at assessing risk. Since both biking and public transit are safer than driving, there are many pitfalls with mandating the use of helmets for cyclists:

- Helmet laws reduce cycling rates since they add an additional barrier to biking. For example: An Australian helmet law decreased children’s cycling in New South Wales and teenage cycling in Victoria by at least 44 per cent after two years, discouraging these populations from pursuing cycling into adulthood. As well, these laws reduce the safety in numbers effect in which having additional people cycling is protective as it increases awareness by other road users.

- The overall health benefits of pedalling and the prevention of sedentary-related diseases far outweigh the negatives of going helmetless; this health benefit holds when factoring in increased exposure to air pollution and collisions. A study shows that people who regularly commute by bike nearly halve their cardiac or cancer mortality compared to those who drive; their chances of dying prematurely by any cause drops by 41 per cent.

- In a study of eight countries, the U.S. was first in both cycling helmet usage and fatality rate, whereas the Netherlands had the lowest helmet usage and fatality rate. This difference is attributable to safer cycling and road networks. The Netherlands/Amsterdam is often labelled as an “exception” when it comes to cycling, but prior to the 1970s, city infrastructure promoted car dominance until the “living street” concept was adopted.

- Helmet laws hinder the bike-sharing programs that are crucial to solving the last mile problem of transit. Public transit and cycling complement one another and cover each other’s weaknesses. Transit is great at quickly and comfortably covering long distances on popular routes, especially if the weather is non-ideal. Cycling is inexpensive and excels at covering shorter distances (beyond walking) on less popular routes. Oh the Urbanity! demonstrated this synergistic effect by calculating that at Montréal’s current population, 150,000 people are within walking distance of the 26 proposed light rail stations for the Réseau Express Montréal (REM) whereas 900,000 are within cycling distance. Helmet laws would significantly dampen this reach.

- There is unequal enforcement of helmet laws with over-representation of both people of colour and of lower socioeconomic status.

- Another issue is risk compensation: People who cycle with helmets feel more secure and engage in riskier behaviour, while drivers see them as less vulnerable and tend to overtake them at a closer distance, potentially mitigating a Québec law that cars have to give one metre of space when passing a cyclist on roads with a speed limit of less than 50 kilometres per hour (km/h) and 1.5 metres when the limit is over 50. In fact, a study showed that 30 per cent of people viewed cyclists as “less than fully human” and this was exacerbated when wearing safety vests and helmets.

- Helmets are tested in the U.S. at a collision speed of 22.5 km/h. While they prevent 63-88 per cent of brain injuries, they have traditionally focused on preventing skull fractures and not concussions and lose effectiveness in higher speed collisions.

As such, the health-care community should be nuanced in its messaging: helmets are important, but there shouldn’t be a stigma associated with going helmetless due to their many physical and psychological limitations. In the end, nothing can be as effective as the development of infrastructure that is adapted to and encourages safe practices by all road users.

Misconception #2: People who cycle put themselves and others in danger

Public perception often labels people who cycle as “rule-breakers” that put themselves and others in danger. However, when cyclists do break the law, they often do so precisely because of safety concerns. The Idaho stop law, in effect in 10 U.S. states, allows cyclists to treat red lights as stop signs and stop signs as yields. The law has decreased bicycle crashes by 14.5 per cent and reduced the severity of these injuries when they do occur. Stopping and starting at intersections is not only physically taxing, it increases a person’s exposure time within the intersection, increasing the chance of a collision. As pointed out by Oh The Urbanity!, we should normalize the idea that different road users have different rules to follow according to their potential to cause damage – this same logic is why there are special licenses and rules regulating heavy trucks and school buses.

Far from cyclists being rule-breakers, cyclists respect traffic laws just as much if not more than drivers. In Québec, in collisions between drivers and pedestrians, the driver was distracted 68 per cent of the time while both parties were distracted 17 per cent of the time. In the Netherlands, where 50 per cent of the population cycles, camera studies determined that 4.9 per cent of cyclists committed infractions compared to 66 per cent of drivers, with the latter’s main infraction being speeding. In fact, speeding isn’t as noticeable to the naked eye as cycling infractions, like running a red light, and thus stands out in the public’s mind. However, speeding is far from a harmless infraction; it accounts for 33 per cent of the 1.35 million people killed on roadways yearly, the No. 8 cause of death globally (outranking HIV/AIDS) and the No. 1 cause of death for five- to 29-year-olds.

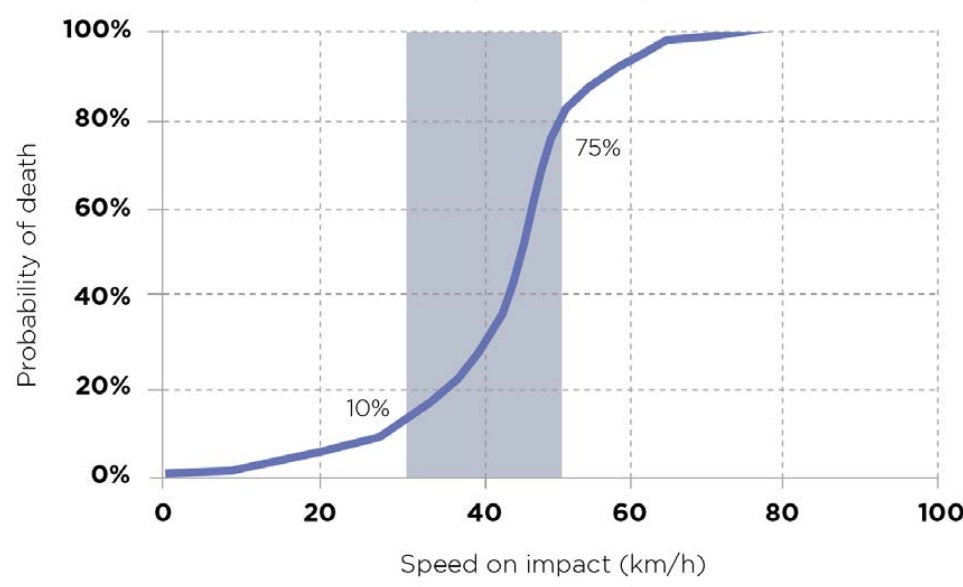

With regards to young victims, the Canadian Automobile Association (CAA)-Québec concluded that 96 per cent of drivers do not respect the 30 km/h speed limit in school zones. In 2022, this resulted in 37,000 fines to drivers committing school zone infractions. Even after 7-year-old Mariia Legenkovska was hit and killed while walking to her Montréal school, LaPresse observed that few who drove in that same school zone respected the 30 km/h speed limit. They recorded the average car speed at 47 km/h, with at least one driver every minute going faster than 60 km/h. This speed difference is important as the mortality rate goes up exponentially between 30-50 km/h (Fig. 1) and stopping distances more than double.

Figure 1: Death probability of a person walking based on vehicle speed (from SAAQ)

Cars pose additional concerns to public health, many of which increase with speed:

- Carbon emissions: Cars pollute 2.5-10 times more per passenger km than bikes, e-bikes, or buses (based on lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions, which includes manufacturing and calories consumed biking) and contribute to air pollution, leading to 15,300 premature deaths/year in Canada. Children and their developing lungs are particularly sensitive to air quality.

- Fine-particulate emissions: A study conducted in Paris concluded that 10 per cent of PM10, airborne particulate matter that are less than 10 microns and originate from car brakes and road-wheel friction, reach deep into lung tissues and can induce adverse health effects.

- Noise pollution: As stated on the YouTube channel Not Just Bikes, Cities Aren’ t Loud: Cars Are Loud, the average traffic noise in cities can reach the level of causing hearing damage. Low long-term exposure is linked to stress, hypertension, heart disease, obesity, increased cognitive decline, reduced sleep quality and quantity and diminished focus. It even impacts our behaviour, making people less social, patient and generous with others. Thus, vehicle noise has a burden of disease similar to second-hand smoke.

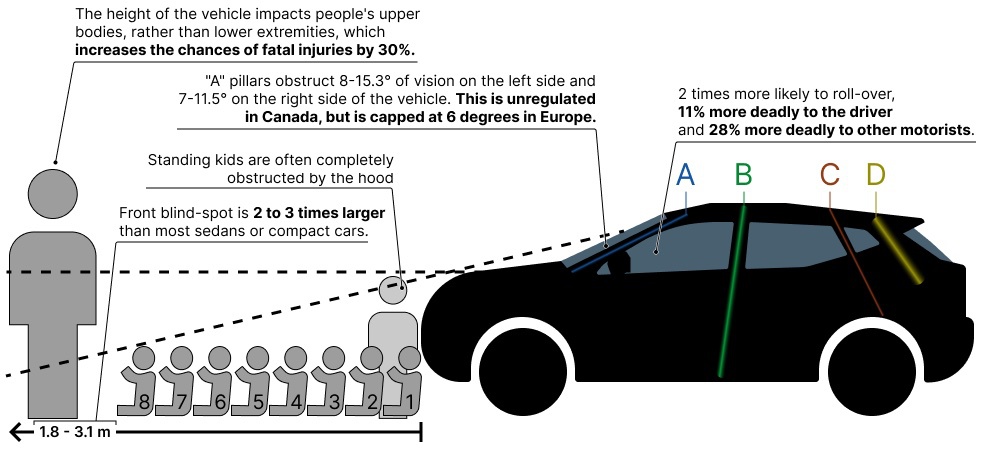

- Increased size of vehicles: The personal use of light trucks (SUVs, minivans, pickup trucks) in Québec has increased by 128 per cent from 2000-2017. These SUVs are responsible for 50 per cent of the rise of greenhouse gas (GHGs) emissions in Québec. As illustrated in Fig. 2, light trucks’ increased height and blind spots cause 55 per cent more severe injuries to cyclists than normal cars, are up to four times more likely to hit people on turns, and have resulted in frontovers that kill 60 U.S. children yearly.

Figure 2: The underappreciated dangers of light trucks (1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

Figure 2: The underappreciated dangers of light trucks (1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

- Electric vehicles (EVs): Unfortunately, EVs aren’t a solution to many of the aforementioned issues. Their quiet nature at low speeds is a safety hazard for other road users. At higher speeds, their rolling resistance is more than that of internal combustion engine vehicles, as they are 33 per cent heavier. Heavier cars produce more of the aforementioned airborne particles and vehicle road damage is exponentially related to weight with a three-fold heavier vehicle causing 80 times more damage.

Misconception #3: Most people would never cycle regularly, especially in winter

A Portland study conducted in 2006 found that people fell into one of four groups in their relationship with cycling: four per cent were Strong and Fearless; nine per cent were Enthused and Confident; 56 per cent were Interested but Concerned; 31 per cent were No Way, No How, those who won’t cycle due to distance, topography, physical ability, or lack of interest. Further studies confirmed that these general proportions hold for metropolitan areas across Canada and the U.S. Crucially, the main concern of the largest group, Interested but Concerned, is that they are insufficiently protected from vehicular traffic.

There are two arguments often cited against cycling’s utility in day-to-day life:

- My trip is too long: Currently, many car trips cover relatively short distances. 36 per cent of car trips are less than five km long and the average commute is 11.9 km. Even in suburban areas, Oh the Urbanity! found that a majority of homes were within easy biking distance (three km/10-15 minutes) of peoples’ most common trips. In Montreal, for trips more than one to eight km distances, bikes often get around faster than cars. Making cycling safe can increase productivity when arriving at work and help decompress when returning home at the end of the day. This will incorporate movement and break up sedentary patterns, a crucial element of maintaining health and exposing people to the benefits reaped from being outside.

- What about the winter?: Extreme winter days are relatively rare in a calendar year. Annually, Montréal averages approximately three to four months of snow on the ground, 14 days of snowfall greater than five centimetres, and nine days with a wind chill below -30 C. In addition, the heat generated by cycling is enough to keep warm on the majority of days. Most cars are only feasible in winter due to extensive snow removal. Making winter cycling feasible requires snow removal from protected bike lanes as well as a culture shift (see the world capital of year-round cycling, Oulu, Finland). There are promising signs of this shift in Montréal, with the city seeing an 83 per cent increase in winter cycling from 2019-2020 and extending its bike-sharing program to the winter months with the help of studded tires.

As noted by Propelbikes, the car is a tool that we’ve overused to the point where the more people that have one, the less useful it is. As a general concept, we should be offering people the freedom to choose between multiple modes of safe and practical transportation. From an equity perspective, this would benefit:

- Groups who have no choice but to drive (i.e., individuals with disabilities, emergency services, non-micromobility related shipping, etc.): This would liberate the road for them. For emergency services, even with Paris’ plans to make the city 100 per cent cyclable, firefighters’ response time has gone down relative to 2015. This is because the new 2.5-metre bike lanes can accommodate emergency vehicles and more cycling has meant less traffic congestion. In fact, some cities have emergency medical service bike teams. Micromobility also solves the last mile problem when it comes to shipping/delivery.

- People who cannot afford a car or who would be more financially stable without one: People underestimate the costs of car ownership by 52 per cent. The average cost of ownership (depreciation, fuel and operations, insurance, tax, maintenance and other fees) in 2022 was $9,282 per year in the U.S. In addition, the average Canadian has $20,000 worth of car debt. Car infrastructure is often imposed on areas where car usage is low; in Montreal’s Parc-Extension, the poorest neighbourhood on the island and among the poorest in Canada, 50 per cent of the population does not use a car, yet bike lanes, public transit and sidewalks occupy only two per cent, three per cent and 20 per cent of the borough’s roadways, respectively. Parking space alone outstrips all of these, taking up nearly 30 per cent of the borough’s public space. Overall, in 2021, nearly 75 per cent of Montreal’s public space was dedicated to vehicles, while cycling infrastructure took up at most 2.5 per cent of public space in a few boroughs.

Figure 3: Positive feedback loops of induced demand (left: abridged / right: expansive ) and their associated costs

| Induced demand (or Braess’s paradox) explains how traffic can’t be solved through additional laneways and eventually impacts pattern development and renders driving a necessity. As such, traffic is not a liquid, whereby increasing capacity increases flow, but rather a gas that fills the available space. Within one year of lane expansion in Californian cities, 60 per cent of the new capacity was taken up with new or longer trips; within five years, 90 per cent was consumed. Biking is also subject to induced demand whereby installing new protected bike lanes results in additional cyclists. For example:

1. The city of Seville, Spain increased its protected bike network from 15 to 120 km over three years, resulting in a bike modal share increase from 0.5 per cent to six per cent. 2. The implementation of the Réseau Express Vélo (REV, Montréal’s Express Bike Network) on St. Denis St. flipped the space allocation from 70 per cent for drivers and 30 per cent for people who walk/bike to 31 per cent and 69 per cent, respectively. The added pedestrians/cyclists resulted in commercial occupancy increasing from 73 per cent pre pandemic to 75 per cent in 2021 and 85 per cent in 2023. 3. Edmonton’s 2017 downtown bike network doubled the cycling count relative to the previous year and was equivalent to 12 per cent of car traffic. In terms of overall costs, for every km travelled, biking results in +0.26$ of societal gains and driving loses -$0.89. This disparity is due to the positive and negative externalities of congestion, collisions, health benefits, noise pollution, infrastructure costs, air pollution, and the benefits of cycling on business. As such, people who cycle not only pay their fair share but subsidize people who choose to drive. |

The current narratives and conspiracies surrounding “15 minute cities” and the “war on cars” is irresponsible. As a society, we need to examine our own blind spots and biases when it comes to all road users to create human-scale urban environments that nudge us toward healthier, safer, equitable and financially savvy transport.

These goals already align with health-care teams’ advocacy work. Be they hospital units, administrations, foundations or health-care societies, health-care teams can play a vital role in promoting urban planning that leads to positive behavioural change.

In the meantime, regardless of how you go about your trips, don’t forget to go “tout doux dans nos rues” (gentle in our streets).

Acknowledgements:

Though not affiliated in any way with this article, the following entities helped inspire the creation of this article:

- Jason Slaughter’s Not Just Bikes: A native of London, Ont., who moved to the Netherlands and tackles “urban planning and urban experiences from the Netherlands and beyond.”

- Jasmine Steffler and Patrick Murphy’s Oh The Urbanity!: They have lived, walked, biked and taken public transit in both Ottawa and Montreal and talk about city streetscapes and demographics.

- Tom Babin’s Shifter: Calgary-based author and journalist covering urban cycling and bike commuting.

- Strong Towns: U.S.-based non-profit media advocacy organization that tackles North American development patterns and urban planning from a financial and fiscal point of view.

I found the article on cycling very interesting but myopic and idealistic. Some big issues were overlooked. First, the matter of the aged. An increasing proportion of our population are or are growing old, and are often (eventually always) unable to move about the city on a bicycle. Other people have disabilities that deny them the luxury of bicycling. Second, are the matter of hills; Denmark and the Netherlands are flat which greatly facilitates bicycling. Electric bikes are an emerging possibility but they are expensive and beyond the budgets of most people. Third, bike lanes – as in Toronto – are often murderously dangerous for pedestrians to cross. Traffic in them is silent, and includes wheeled vehicles of so many different varieties and speeds and travel characteristics – many are motorized now and all rush into the traffic-free bike lanes. many of the bicylists are delivery vehicles whose riders are paid more for their speed than their safety (either for themselves or for the public). Crossing at lights is honestly more dangerous than I ever remember. Further, empty or near-empty bike lanes infuriate car drivers, making them impatient, angry and sometimes so outraged they are overtly hostile to bicyclists. Also bicycles are not useful for doing the shopping or collecting kids from daycare etc – making them less use-able by women and for doing many of the activities of daily living that need to be combined with trips to and fro work.. and, yes, there are only some days that the streets are fully impassable cause of snow, but i have lived in Montreal and know that the snow banks and salt-melt ice and other winter detritus never will allow bicycles to be seriously used much in winter. Riding in the rain is doable with good rain gear, but riding in -30 C in Calgary is not doable.

I am not a pro-automobile person for sure, and i am a serious environmentalist, and i have spent my career in the public health field – but i feel that the bicycle solution in Canada is too idealistic, impractical and structurally limited to take us very far.

Complete Streets + Green Streets have bicycle circulation components as an integral aspect of the elements to be integrated into the designs / sections / profiles. So if Urban Planners are doing their job(s), then bicycle lanes / paths are a part of the program.

I won’t ride without my helmet. Having been riding for over 50 years and smashed my head on the pavement skateboarding and biking, I chose safety over ease everyday of the week.

Hi Martin,

Thank you for your comments!

I think it will help greatly if the medical community as well as others were in line with urban planners who may know what’s best, but their hand is forced by car-centric pressures.

For helmets, we wanted to expose the nuances of the discussion and I don’t believe it’s simply a matter of safety vs ease. Global cycling network recently released an interesting video on high-visibility wear that really explores how the story is not so straightforward: https://youtu.be/33GpfTWdk8U?si=BD6JUjMvuVxR8Muk

I find wearing a helmet quite comfortable (particularly in the winter, where I wear a skii helmet), but I do know that it has drawbacks on the prevention side.

Brilliant article, thanks: especially the bit about cycle helmets!

Hi Richard,

Glad you enjoyed it! I would invite you to check out the YouTube link I posted in my reply to Martin. It talks about high visibility wear and the intricacies of the research behind their effectiveness.