As cities increasingly redesign their layouts to include bike paths, protesters and some governments often rely on the same post-truth refrain: “I’m not against bike lanes, but this one doesn’t make sense.” Ontario Premier Doug Ford and Transportation Minister Prabmeet Sarkaria have joined this discourse with Bill 212, Reducing Gridlock, Saving You Time Act, 2024.

The bill requires municipalities to get provincial approval for any bike lane that would remove vehicular traffic while simultaneously preventing people injured or killed while cycling from suing the government. The bill also allows the province to remove existing bike lanes on three significant arteries in Toronto – Bloor Street, Yonge Street and University Avenue.

Beyond being a jurisdictional overreach, there are numerous issues and inconsistencies behind this bill and other bike lane protesters. Oftentimes, these protests take issue regardless of where the bike path is installed: if on a main street, this would “worsen traffic” if on a minor one, this would “take away parking.”

Frustratingly, there’s either no alternative plan presented or one that would essentially permit only a disconnected patchwork of bike lanes. As such, statements like “I’m not anti-bike lanes … I’m against the way they’re implemented” are thinly veiled disguises that acknowledge the popularity and benefits of biking infrastructure, but don’t want to change their current way of living and/or is a means of scoring political points at the expense of society.

Many of the follow-up arguments used against bike lanes are frequently a mixture of three things:

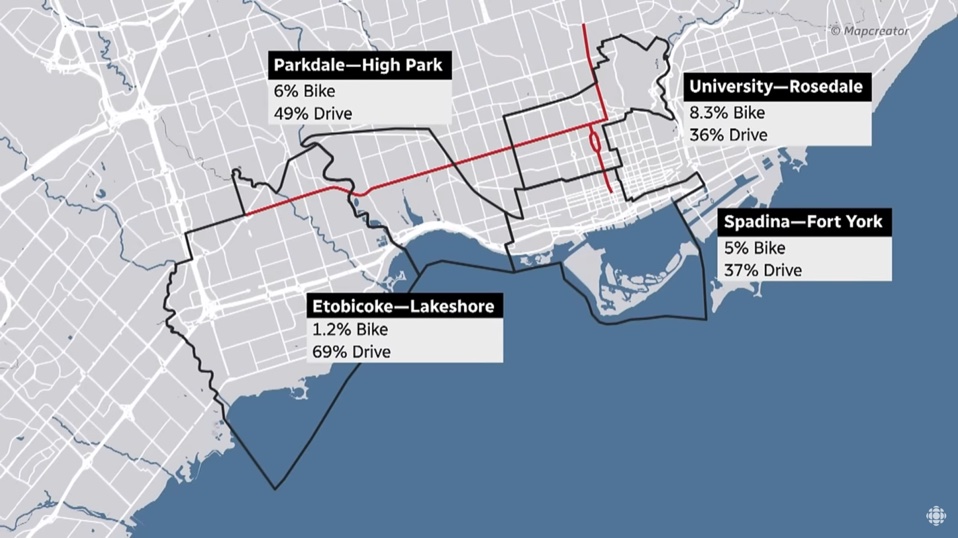

- Confirmation bias: Selectively picking evidence while ignoring conflicting data. In the case of Bill 212, the Ontario government ignored its internal documentation showing the bill likely won’t ease traffic. It cherry picked statistics like: “We know that these bike lanes where only 1.2 per cent of people use to commute to get to work are taking away almost 50 per cent of the infrastructure on those streets … 70 per cent of the population travels to work by car.” Not only does this statement not consider trips beyond commuting back and forth to work, but it conflates statistics that don’t belong together. This 1.2 per cent comes from the Toronto census metropolitan area (CMA) that covers 6000 square kilometres and regions that are far from the three contested bike lanes on Bloor, Young and University. Though unclear, the 50 per cent mentioned is probably an exaggerated estimate of the area covered by these bike lanes on those three specific streets and is not representative of the space that bike lanes occupy over the entire Toronto CMA. This comparison of percentages is not appropriate given the statistics are drawn from vastly different areas. As shown in Figure 1, bike usage in Toronto differs greatly in accordance to proximity to these bike lanes.

Figure 1: Biking and driving commuting modal share in the Toronto CMA (taken from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ScwcEVzmCU4)

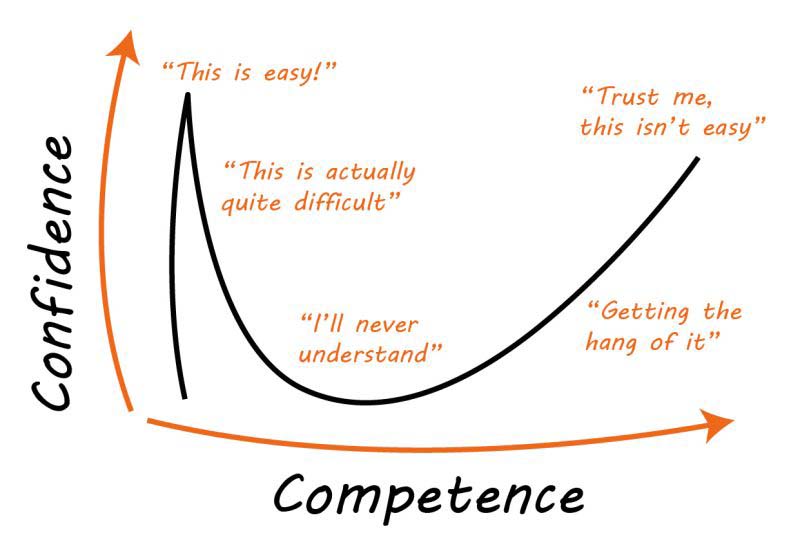

- The Dunning-Kruger effect: People whose urban planning knowledge is solely based on limited and biased anecdotal lived experiences with driving are overconfident in their beliefs relative to their true competence in the domain (Fig. 2). For example, when the premier was challenged on the bill reducing traffic, he responded: “That’s a bunch of hogwash … I know this city like the back of my hand.”

Figure 2: The Dunning-Kruger effect (taken from https://www.asprayfranchise.co.uk/dunning-kruger-effect/)

- Simply false: Premier Ford said “You don’t clog up traffic just because of their political beliefs.” Not only does this go both ways, but we know that the bill is not based on fact.

To illustrate this point, let’s examine the six most cited statements against bike lanes using statistics from my home city of Montréal.

Statement #1: “No one bikes here anyway”

Should a city only build a bridge based on how many people are swimming across the river? No and this is the principle of induced demand, whereby “if you build it, they will come.” We know that the absence of people biking is not due to a societal lack of interest or inability since this only represents 31 per cent of the population. Rather it is due to a lack of supportive infrastructure (a continuous network of safe protected bike lanes, secure bike parking, etc.) that makes cycling unattractive to the 56 per cent of the population that is “interested but concerned,” like families and children. John Forester’s principle for vehicular cycling (that, is cyclists fare best when they act and are treated as drivers of vehicles) is only appropriate for specific use cases and for the 13 per cent of the population that is “strong and fearless” or “enthused and confident” about biking (to learn more about this principle, please listen to “Vehicular cycling and John Forester” parts 1 and 2). We can’t base building bike lanes solely on the current presence of people biking in a specific area or location.

Statement #2: “The bike lanes are always empty”

Most likely, this is an anecdotal statement as bike lanes are far more efficient at moving people and a bike’s footprint is much less noticeable in terms of size and noise than vehicles. However, this could be true if the aforementioned supportive infrastructure doesn’t take people where they need or want to go, since biking isn’t solely recreational.

Statement #3: “Bike lanes will make traffic worse”

As per Braess paradox, adding more vehicular traffic lanes doesn’t improve travel times as this simply induces further demand. As mentioned in #2, cars are by far less space, time and cost efficient (this is addressed in statement #5) at moving people than walking, biking and public transit. For example, despite Montreal’s public transit and biking reputation, this takes up a combined 2.3 per cent of the city’s road systems, whereas 73.8 per cent is dedicated to vehicles, with the balance being for people walking. Toronto having the worst congestion in Canada and third worst globally is a symptom of its car centric design and not because of its limited bike infrastructure. One more lane will not solve traffic.

Statement #4: “Bikes aren’t practical for families, the elderly, disabled, long-distance, winter, etc.”

People underestimate the power and flexibility of bikes and the different types available. These have been used by families (New York City’s Cargobikemamma), gardeners, plumbers and others and solves the last mile problem for business and parcel deliveries.

As well, people overestimate the utility of cars. Most car trips are done over short distances with an average occupancy of 1.5 people. In winter, both cars and bikes are effectively useless without proper snow removal. In addition, extreme winter weather is relatively rare over a calendar year, even in Montréal (and Toronto has almost half of Montréal’s snowfall), but these are more memorable and stand out mentally. Even if bike lanes could only be used part of the year – though Finland’s Oulu, the world capital of winter cycling proves otherwise – should we use this same argument for outdoor soccer fields or children’s playgrounds?

For the disabled, elderly and those with medical conditions, we need to consider that bike lanes are also utilized by wheelchair users and that 25 per cent of Canada’s population doesn’t have a valid driver’s license. Car centricity severely limits the autonomy of these populations and feeds into the concept of the social model of disability that the environment and society is more disabling than the disability itself (turning an impairment into a disability).

Statement #5: “Bike lanes are costly to business and society… and what about my parking?”

Despite Sarkaria saying bike lanes hurt small businesses, the Bloor Annex Business Improvement Area (BIA) is against the removal of these lanes. This is because bike lanes generally increase business sales, decrease business vacancy rates and have a similar effect as pedestrianized streets, which was equally polarizing for a vocal minority.

Ford often cites bike lanes as the cause of billions of dollars in lost productivity. However, his administration fails to consider the true cost of cars and parking. Cars are heavily subsidized. As such, people who don’t use cars still pay, at the very minimum, their fair share while also doing exponentially less damage to public infrastructure. In addition, driving costs the average Canadian over $16,000 per year.

Parking, which takes up significant public space, is also subsidized. Free or underpriced parking costs Montréal $500 million annually while the city’s entire cycling budget only recently doubled to $41 million. Montréal has 21 square kilometres of paved parking, on the level of Montréal’s largest borough (Côte-des-Neiges—Notre-Dame-de-Grâce). Parking minimum laws result in a positive feedback loop of increased distances between destinations, further incentivize car usage and increase housing prices. In fact, both bike parking and curbside patios bring in more revenue for businesses than car parking.

At the end of the day, we have to acknowledge that a parked car uses a public space for a private possession, spends 95 per cent of its time stationary and the space itself can accommodate fewer and fewer cars given the trend of increasing vehicle sizes that rival Second World War tanks. Parking is a significant opportunity cost.

Statement #6: “Bike lanes are dangerous.”

Despite the fact that current road laws aren’t adapted to the realities of biking, people who bike respect traffic laws more than drivers. This goes opposite to most of our observations, but that’s because the most frequent car infractions, like speeding, aren’t obvious and/or are normalized. In fact, 96 per cent of drivers do not respect the 30 km/h speed limit in school zones.

Instituting bike lanes can improve safety by narrowing streets, increasing driver awareness of speed, and induce drivers to respect the indicated speed limit. This is even more reason not to implement bike lanes solely when the street is “wide enough” or on “secondary roads.”

Importantly, biking’s health benefits outweigh the risks posed by collisions. Driving, instead, is not only a sedentary practice, but also contributes to global warming, airborne fine-particulate matter and noise pollution, which all have significant deleterious health impacts. The letter published in Healthy Debate signed by 120 physicians and researchers addresses this perfectly: “Bicycle lanes benefit all road users, and it is much preferable to prevent motor vehicle trauma than to try to treat it.” The Ford government is openly admitting that this bill is prioritizing travel times over safety by preventing citizens from suing the government for biking injuries and deaths. Ford attempted to make a safety argument by stating that bike lanes impact emergency response times, but the City of Toronto’s emergency medical services (EMS) have found no such impact.

Despite all this, to label cars “bad” and bikes “good” would be false and far too simplistic. They, along with public transit, walking, micromobility and other modes of moving about are all tools in the transportation toolbox. Equitable redistribution of public space that would give people the freedom to choose between multiple modes of safe and practical transportation is hampered by the uninformed and short-sighted rhetoric of “I’m not anti-bike lanes… I’m against the way they’re implemented.” This is ultimately detrimental at the societal and individual levels from a health, environmental, economic and equity perspectives.

The comments section is closed.

Adamo, I agree with your presentation completely. For the Ontario government it’s never been about …logic. I want to share an approach that can go beyond logic to build bridges on the emotional level. It could help you a lot when discussing health with patients, when they might refuse advice of their treating physicians. Chris Voss came up with something called the Accusations Audit. It is a list of reasons the other side has against your position and maybe even against you. With Doug Ford, one such item could be, Doug, you opposed bike lanes on major streets since the first one was installed. You never saw their value but saw them as something that just makes car congestion worse. It lists their strongest reasons regardless how true they actually are, what matters is… it’s true for them. This demonstrates empathy and can go a long way to calm them down. It’s surprisingly effective.

Hi Doug,

I will look into it! Thank you for the suggestion.

Ok you have covered the fit young men who are politically active you like drive bikes to work for an hour in February.

How about the rest of us? Why not complete the Eglinton and Finch West LRTs before you start closing the Finch station to start a third subway?