As United States (U.S.) President Donald Trump threatens to unravel New York City’s (NYC) congestion pricing, let’s take a look at what the program has been able to do in just one month.

After being proposed in 2007, again in 2017, agreed to in 2019, approved in June 2023, put on hold June 2024, revived at a lower cost in November 2024, NYC’s congestion pricing finally began on Jan. 5.

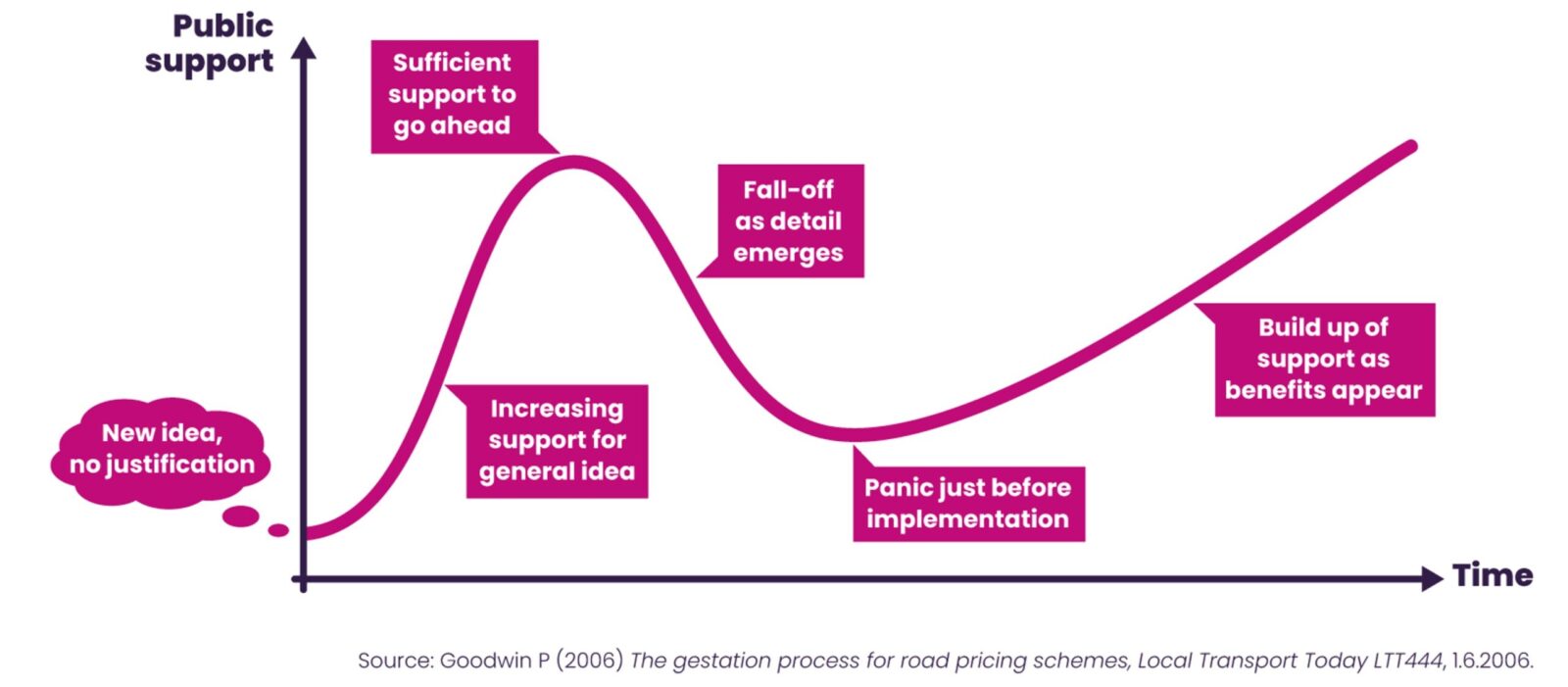

Several versions of road pricing have been proposed for Vancouver and Toronto in recent years, but these were shut down. In NYC’s system, electronic license plate readers charge vehicles a user fee to enter Manhattan’s central business district (CBD, Fig. 1). Generally, you are charged less during off-peak hours, if you have a smaller vehicle or if you’re from a lower income bracket. Emergency and public transit vehicles, and people with disabilities are exempt.

Though several cities around the world use some version of congestion pricing, NYC’s is the first system to be installed in the U.S.. The fees are to be used to fund New York’s massive public transit that accounts for 40 per cent of all the country’s public transit trips. The goal is to reduce the 700,000 vehicles that enter the CBD daily, which is the root cause of 11km/hour average traffic speeds, USD $20 billion in wasted time/lost productivity, slowed emergency response times, crashes and air and noise pollution. The results so far are eye-opening:

1) 273,000 fewer cars entered the CBD and inbound river crossings travel times were 30-40 per cent faster.

2) Subway ridership was up 24 per cent and buses were as much as four minutes quicker.

3) When comparing the same first 10 working days in 2025 to the five years between 2020 and 2024, crashes and injuries in the area have decreased by anywhere from 28 per cent to 77.5 per cent.

Figure 1

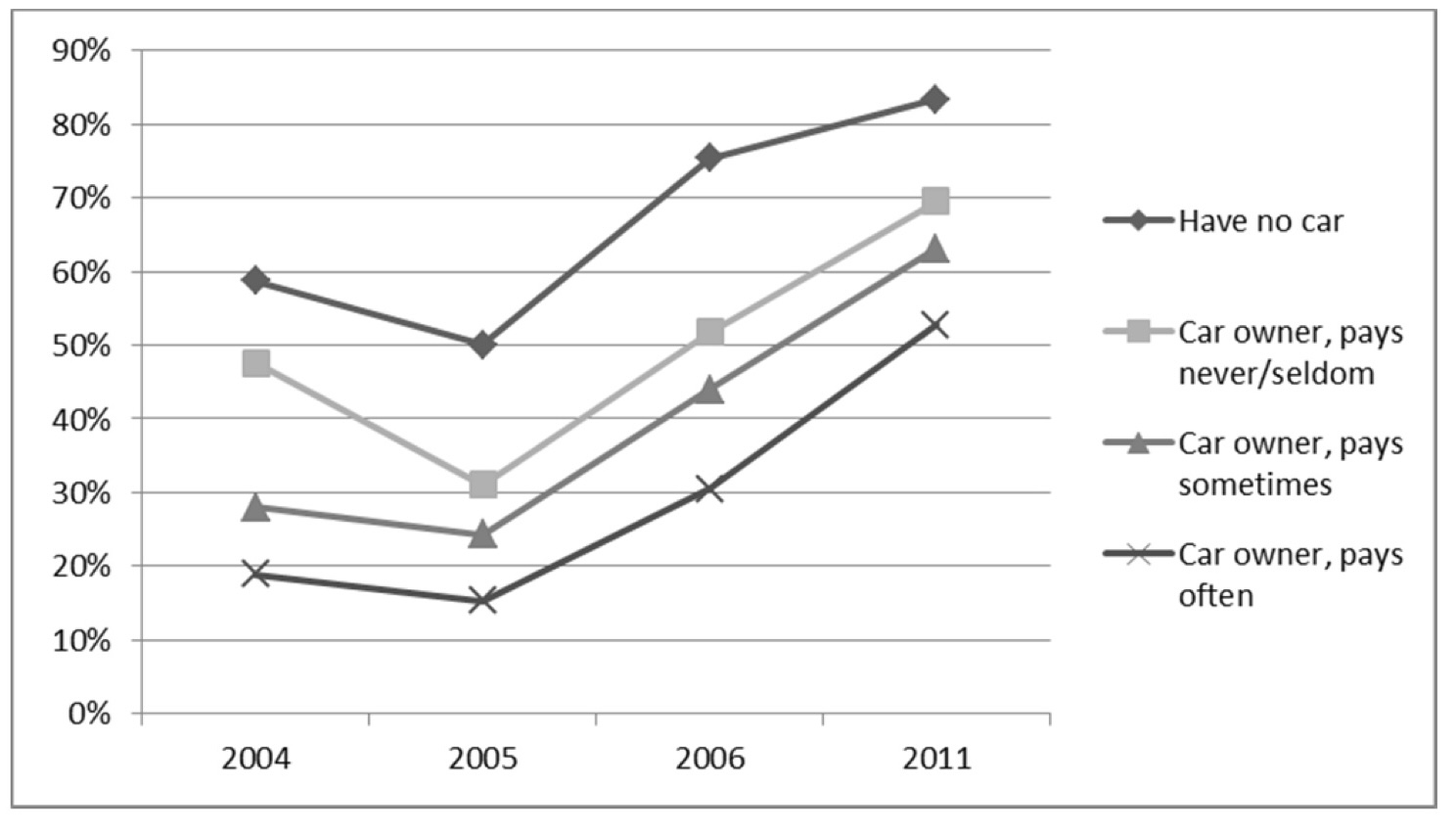

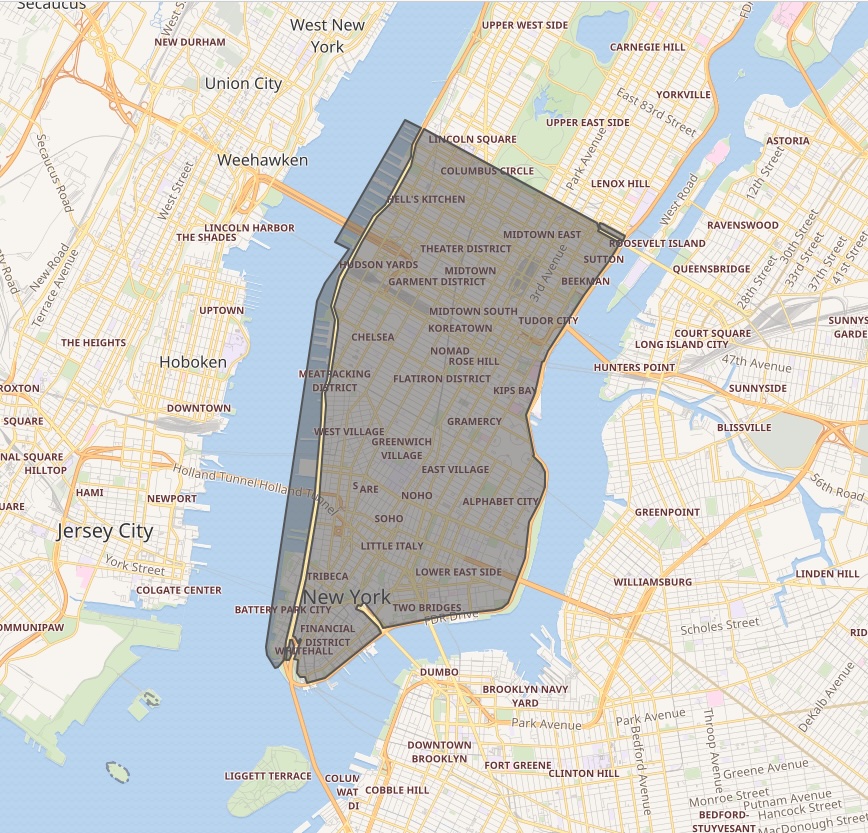

Despite the prolonged timeline, many have claimed this project wasn’t well studied, would impact businesses and reroute traffic while exposing New Jersey to increased pollution and congestion. Assuming these arguments were made in good faith, this phenomenon and variation of public support over time is known as the Goodwin Curve and has happened before with congestion pricing (Fig. 2). Prior to implementation, congestion pricing in Stockholm was relatively unpopular with public support dropping below 40 per cent. However, after a six-month trial period in 2006, 52 per cent of residents voted in favour; by 2011, 70 per cent of the public and even 50 per cent of those who paid the most approved of the measure (Fig. 3).

The change of heart came as residents saw the benefits: car trips dropped immediately by 20 per cent, reducing congestion and emissions, improving travel times and resulting in a 50 per cent reduction in pediatric asthma attacks. From 2007 to 2020, despite a 26 per cent increase in the city’s population, traffic dropped by 22 per cent, greenhouse gas emissions decreased by 14 per cent, and transit ridership went up five per cent. It’s important to note that this congestion pricing was combined with expanding public transit along with park-and-ride facilities (driving and parking your car in an area prior to taking public transit).

Figure 2

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 3

Beyond Stockholm, a systematic and scoping review have both shown the positive impact of the combination of congestion pricing and public transit:

1) A 2021 scoping review that included 15 studies on road pricing and transportation and health in London, Stockholm, Gothenburg, Milan and Singapore showed a decrease in:

- Car trips.

- Air pollution both in and outside of the congestion zone. One study found that congestion pricing reduced health inequities in London through greater reductions in pollution in less affluent neighbourhoods, which had higher amounts of pollution to begin.

- Asthma attacks.

- Road traffic collisions, all while decreasing or keeping collisions constant outside the priced area.

There were increases in:

- Public transit usage.

- Life expectancy, with an estimated 183 years of life gained per 100,000 people living within London’s congestion pricing and 18 years outside the road pricing area. In Stockholm, it was 206 years per 100,000 people.

2) A 2023 systematic review of 16 studies evaluating the longitudinal effect of low emissions zones (areas that ban or charge vehicles above a certain emission standard) as well as congestion charging zones in multiple German cities, Tokyo, Japan, Milan and London found that most studies showed reductions in:

- Cardiovascular diseases (ischaemic heart disease, hypertension, cerebrovascular disease).

- Road traffic injuries.

- Pollution and particulate matter.

One negative impact of these measures in London was a reduction in visits to family and friends. This may have downstream impacts on social isolation and health, highlighting the importance of crafting a congestion pricing plan that considers vulnerable groups like low-income individuals that may not have access to viable transit, as they will be disproportionately impacted by congestion fees.

This shows that combining road pricing measures with a “viable” transit system is key. As Enrique Peñalosa, the former mayor of Bogotá, Colombia, said: “ An advanced city is not one where even the poor use cars, but rather one where even the rich use public transport.”

A viable transit system doesn’t mean it has to turn a profit as: 1) transit systems rarely pay for themselves directly – the average fare box recovery rate in the U.S. is 33 per cent; 2) cars are far more expensive while being the least efficient at moving people. Car-centricity severely limits the autonomy of 25 per cent of Canadians who don’t have a valid driver’s license because they are too young, simply choose not to and/or have a contra-indicated disability and/or medical condition.

An analysis by a group at the Université de Montréal Hautes Études Commerciales showed that on the Island of Montreal, the social costs (government money plus the cost of negative/positive externalities in the form of pollution, health benefits, accidents) for each mode of transport were:

– Automobile: $9,014/person/year.

– Public transit: $2,449/person/year.

– Bike: -$338/person/year.

– Walking: -$28/person/year.

(The latter two modes had an overall net savings due to their positive externalities being larger than the government money put in.)

As such, it’s misleading to frame spending public money on transit as “funding” but when it comes to roads, as “investment.” Public transit should be framed as a “public good that we recoup some of the costs of with fares” and that every $1 invested results in $5 of economic gain. As such, a viable mode of transport can take many forms (buses, trams, light rails, railways, subways/metros, tram trains, gondolas, cable cars, funiculars, ferries) with their own pros and cons, but regardless they should prioritize five elements:

1) Connectivity: People should be able to get to their destination quickly and easily. Transfers between different public transit entities (metro, bus, train) should be facilitated via clear signage. As per the Downs-Thomson paradox: “Traffic will increase without limit until the option of public transport (or any other form of transport) becomes faster than the equivalent trip by car. It draws the conclusion that people do not care whether they drive, walk, bike or take the bus to any location – they just want to get from A to B in the fastest and most convenient way possible.”

2) Reliability: It’s essential to run frequent service on schedule with limited delays and waiting periods, since transit wait times are weighted 1.5-4.5 times relative to car time (a 10-minute transit wait is perceived as a 15-45 minute drive). Having transit signal priority (traffic lights favouring public transit) and other priority measures (bus lanes and queue jumps) prioritizes moving the greatest number of people faster, encouraging more people to use it, further increasing its efficiency.

3) Method of payment and pricing:

- Reduced fares for individuals of low socioeconomic status.

- Fare capping that ensures riders don’t spend more than a certain amount on public transit per week and/or month.

- Offer the option of contactless payment and not require a special transit card/ticket to simplify barriers to entry for infrequent users (tourists, new users). Cash should nonetheless be an optional form of payment as 18 per cent of Canadians have little to no access to a bank account and others still rely on cash.

4) Accessibility:

- Elevators are not only necessary for people in wheelchairs, but also useful for people with strollers, walkers/canes, luggage, a bicycle as well as those who are pregnant.

- Similarly, level boarding (whereby the platform is at the same height as the metro or train) is important for the 20 per cent of the population with mobility issues. Level boarding removes a potential tripping hazard as non-level boarding is the largest safety and fatality risk in the United Kingdom’s railways and forces wheelchair users to call ahead of time to request a ramp. Level boarding also allows for faster boarding/deboarding.

- Lastly, there needs to be a foolproof plan for everyone to be able to exit and get to their destination in case of emergency or shut down.

5) Safety: Public transit is exponentially safer relative to a private vehicle, as property crimes are 500 times less likely and the chance of a violent crime is far less than the risk of traffic accidents. In addition, platform screen doors (complete floor to ceiling barriers) can help:

- Prevent accidental falls, suicide attempts and homicides by pushing.

- Eliminate delays due to unauthorized people accessing the track (a security risk), or via dropped items or litter, which poses a fire risk and can damage the train if it accumulates.

- Lower manpower costs through automation, since a conductor is no longer needed to stop the train in the above-mentioned situations.

- Reduce the wind felt by passengers, which can result in loss of balance and/or falls due to the piston effect, and which also reduces background noise allowing for clearer platform announcements.

- Reduce the indoor particle emissions and pollution caused by the friction between the train wheels and the tracks.

- Improve climate control.

As both history and New York’s experiment has shown, a well-thought out congestion pricing plan that helps fund a viable public transit and other methods of transportation, regardless of its initial popularity, will ultimately benefit everyone due to increased traffic flow, better usage of public funds, economic development and population health and equity.

The comments section is closed.

The road tax in New York has proven to be nothing more than a cheap money grab.

My daily drive from New Jersey into lower Manhattan has remained exactly the same.

Stop spreading the elitist, ableist greenwashed propaganda. This hurts the middle and working classes

Yeah at the expense of the health of the peopls of the Bronx. But they’re poor, so we don’t have to care about them, now do we.

I can’t imagine how any sensible person thinks changing and restricting travel for Additional money is good it keeps the hardest working people at bay. To finance a giant conglomerate is absurd Plus thinking your saving Earth is a complete fantasy